GOVEDARE catalogue

advertisement

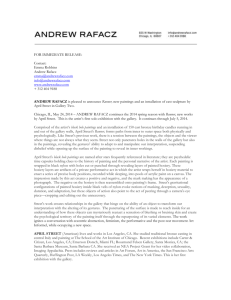

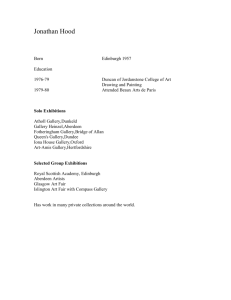

Philip Govedare l a n d s c a p e s Philip Govedare l a 1 n d s c a p e s 2 3 “The beauty of painting is that it has all of history to refer to and be informed by…it mines the past in every possible way,” “My work evolved out of abstraction and as I worked further, it became clear to me that I was really painting landscape. At one point, I decided to embrace the subject with all its history, complexities and layered meanings.” Excavation #9, oil on canvas, 68” x 60”, 2014 4 “The beauty of painting is that it has all of history to refer to and be informed importantly, what we don’t know. Although many of his current works take the ing a narrative, which is revealed for its dependence on partial knowledge of all Ultimately, Philip Govedare’s recent work is a superbly agile synthesis of global by…it mines the past in every possible way,” Philip Govedare says. perspective of aerial views of the Earth’s surface, they are not attempts to depict kinds—the memory of an old photograph, a glimpse of a man disappearing around trends from across the arts and a remarkably effective commentary on contem- an actual place. Instead, the art viewer may be surprised to learn that the view- a corner, a document filled with statistics, the suddenly remembered sound of porary visual culture. By incorporating those trends into a personal reworking of “My work evolved out of abstraction and as I worked further, it became clear points represented are a “purely invented perspective.” a waterfall. What becomes unsettlingly clear is that what we understand as the traditions in American painting, Govedare erodes the commonly held assump- to me that I was really painting landscape. At one point, I decided to embrace With no clear real world referent, by working against the viewer’s expectations, truth of our present moment is as dependent on the suppression of some things tion that vision is immediate and unflinching—a direct, uncomplicated path to the subject with all its history, complexities and layered meanings.” his work begins opening up the space in which we come to understand what we know as it is on the foregrounding of whatever details come to consciousness knowledge. By constructing his painted landscapes as documentary fiction, he pictures tell us. “By creating this kind of a distance between the viewer, which in that moment. Ristelhueber’s photographic exhibitions work much the same draws the viewer into his paintings in ways that begin to reveal the processes by Govedare exercises what has become a profoundly imaginative compositional is a physical distance of the aerial perspective, just this kind of epic scale of the way, detailing landscapes with a strangely evanescent quality that refer, only el- which we see both real landscapes and pictures of them—processes that enact license: his work now alternates aerial perspectives with ground level views in painting in terms of what I’m depicting, makes us think, or ponder, or reexam- liptically, to what we normally suppress in looking at them: the forces that shape narratives that structure the ways we think about the world and our place in it. a manipulation of scale and form, detail and structure. These recall the exper- ine our place in the world,” he says. Unencumbered by the need to reproduce the places we look at in her photographs of Mostar, Sarajevo, Srebrenica, Beirut. To put it another way, just because you’ve looked at something doesn’t mean you iments of well-known contemporary photographers like Sophie Ristelhueber natural views, Govedare’s work deliberately walks a fine line between the famil- and Emmett Gowin. Govedare employs these alternating perspectives to picture iar and unknown, between the taken-for-granted and the strangely disquieting. wide extents of the Earth’s surface, imagined worlds that result from a blend “There’s a tension between the depiction that I create and the source of where it of personal memories and historical knowledge. There are fleeting glimpses might have been in the world. So, the color that I use is more about light than it and sustained views as well as remembrances of being present in places, and an is about literal transcription, and I think then it starts to elicit certain questions. awareness of what has happened and continues to happen to the environment The forms in my work could be roads, they could be mining, or they could be in landscapes from eastern Washington to Utah. Significantly, both Gowin and caused by natural erosion.” Ristelhueber are known for depicting devastated landscapes. Govedare’s work is similar, drawing and painting the kinds of troubled places he can’t get out of his mind. “I was flying back from southern Oregon, and you look down and it looks like farmland. There’s a checkerboard pattern from the clear-cutting of the forest,” says Govedare. Things that appear one way from ground level tell a very different story from above. Those aerial views inhabit his consciousness in a way that change his perspective on what we see while we’re on the ground – what turns out to be but we usually fail to recognize are only partial views. For him, being in a place is very meaningful in itself, but it is still only part of a larger picture. In the same way, Govedare’s paintings produce a sense of unease through the creation of a carefully manufactured documentary fiction. Similar to both Sebald and Ristelhueber, Govedare uses the translucent qualities of light, the fragile inscription of lines, the unexpected appearances of color, and the lack of a clear referent in subject to produce familiar yet strangely unreal scenes that arrest the viewer’s gaze. In a work like “Melt” for example, the origins of the lines that trace back delicately into the distance on a high plateau are not clear. Are they natu- And while painting fictional landscapes may seem like a radical departure from ral or manmade, more permanent or relatively temporary? Are they scars upon the Hudson River School, it is very much in line with recent experiments in other the land? Their indistinct nature is reinforced by the way Govedare causes them to art forms, from photography to literature. Particularly compelling is a comparison float above the surface of the paint. While a sense of wholeness and completion in of Govedare’s work with the writing of W.G. Sebald, who breaches the boundaries a painting (or a photograph, or an essay) always provides the viewer with a set dis- between fiction and fact in critically acclaimed works such as The Rings of Sat- tance—we might say a register—from which to consider, to contemplate, to think urn, Austerlitz and On the Natural History of Destruction. Haunted by a sense of about the subject of a scene, partly because it records a temporal stoppage, Gove- abstract distance, Sebald’s prose seems to refer to subjects only obliquely. Mixed dare’s paintings have an indistinct quality about them, as if we are viewing it in the with grainy photographs and documents that often seem placeless or in various process of unfolding. Representing a kind of imperfect knowledge, these paintings states of decay, the pages of his books have a ghostly, unsettling quality. Ulti- put the viewer in the position of recovering and completing what is to be known It is significant to note that Govedare’s work is similar to well-known artists from mately, Sebald’s writing brings to the foreground the ways we build and under- about a scene, a place. “I think what you don’t describe, what you leave open to other fields who attempt to synthesize experiences of imperfect knowledge. The stand narratives by anchoring them to details and facts—things we can comfort- the imagination is a critical part of the painting or drawing” says Govedare. “It’s irony of course is that, in a world overflowing with information, what arises is ably locate in the real world. Yet, these details take on a strange impermanence like poetry: you give a certain amount of essential information but the reader, then the need to question what we actually know, how we know it, and perhaps most when we are forced to think about how they work in the service of construct- brings his own imagination and experience to the work.” have seen it. Govedare’s art is the kind of work that gets us to look twice, and to look deeper. It encourages us to see. Perhaps most importantly, it’s the kind of work that gets us to take that effect with us, out into the street, where we can once again look with fresh eyes at the world around us. Jim Ketchum Jim Ketchum is a geographer and Senior Writer at Island Press. He co-edited the book, GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place 5 7 6 Mesosphere, oil on canvas, 63” x 74”, 2013 Excavation #7, oil on canvas, 48” x 80”, 2013 9 8 Nebula, oil on canvas, 31” x 54”, 2014 City #2, oil on canvas, 36” x 72”, 2013 11 10 Excavation #4, oil on canvas, 70” x 64”, 2010 Excavation #8, oil on canvas, 66” x 61”, 2014 13 12 Melt, oil on canvas, 66” x 62”, 2012 Excavation #6, oil on canvas, 66” x 59”, 2010 15 14 Excavation #5, oil on canvas, 48” x 90”, 2010 Black Lake, oil on canvas, 50” x 82”, 2011 17 16 Cloud Series #5, oil on paper, 11” x 12 ½”, 2013 Cloud Series #6, oil on paper, 9” x 12”, 2013 Cloud Series #7, oil on paper, 7½” x 12”, 2013 Cloud Series #8, oil on paper, 9” x 12”, 2013 Cloud Series #9, oil on paper, 11” x 15”, 2013 19 18 Burn, ink on paper, 12” x 18”, 2007 Burn #2, ink on paper, 15” x 11”, 2013 31 Canyon, ink on paper, 12” x 18”, 2007 21 20 Circo Massimo, ink on paper, 12” x 18”, 2007 Colosseo, ink on paper, 12” x 18”, 2007 23 22 Creek, ink on paper, 12” x 18”, 2007 Inlet, ink on paper, 15” x 11”, 2012 River, ink on paper, 12” x 19”, 2013 25 24 Summer Bluff, ink on paper, 12” x 18”, 2011 Emigrant Lake, watercolor on paper, 11” x 15”, 2011 27 26 Excavation, oil on canvas, 60” x 55”, 2008 Flood, oil on canvas, 59” x 56”, 2009 Interview – 10/20/2013 JK: Can you tell me how you approach painting? What’s your creative process both in a putting-paint-to-canvas sense and a broad conceptual sense? 28 PG: Well, first of all, I work on the larger paintings for months. It could be a year or more. And I do work on more than one painting at a time. The reason for that is I like to be able to get away from the experience for a time. Unlike a lot of painters, I don’t typically leave my paintings facing outward in the studio. I turn them to the wall and I would like, ideally, to be able to come in and see what I’ve done previously and see it somehow with a fresh eye. Everyone has these personal idiosyncrasies and that’s one of mine. When I envision some kind of landscape, I don’t have a clear idea of what I want to paint, I just have a general sense of scale, an orientation in terms of horizon line, maybe… maybe a condition of light or time of day or geographic location, but really it’s very open. In that way I kind of stumble through the process. Painting is a very inefficient process for me, but it’s the only way that I can arrive at something that feels fresh, surprising and unfamiliar. I was influenced very much by the processes and approaches of the abstract expressionist painters – just the idea of the painting being an existential encounter, that the whole process was an act of self-discovery, and I think that’s something original in American painting starting maybe as far back as Albert Ryder or even George Inness. My process is one of observation in the real world as a starting point, and then engagement with process and material to find imagery that arrives at a place that I would not have anticipated and that’s kind of a surprise to me – an intersection of reality and imagination that has a compelling presence, both familiar and strange at the same time. Albert Ryder is an artist whose work interests me because of the content of his work–a solitary figure out on a boat in the ocean. And that appeals to me, too – this relationship of the individual to nature or place in the universe, but also his way of working, his very unorthodox way of combining materials and processes. A lot of his paintings over time, even in his lifetime, were damaged and they cracked, but in interesting ways. They were organic, kind of living things. My own work evolved out of abstraction that was grounded in a reference to landscape. And then as I worked further, it became clear to me that I was really painting landscape. I went back out and I found this site, the Duwamish River, in south Seattle. A superfund site that has a history of dredging and heavy industry, it was also an Indian fishing ground and village, so it was loaded with this history but also with this mix of nature and industry. I went down there and I started doing a lot of drawing, and I ended up doing a series of paintings. After I finished that series of Duwamish paintings, I went back to a kind of abstraction in the aerial landscapes, but I didn’t leave observation. I recently started a series of cloud studies, which are partly observed and part imagination. One thing that really interests me is the intersection of observation, memory, and imagination. For example, the paintings that I do are clearly informed by being in a place, observing certain phenomena, but not being limited to that. I recently told some of my students that I was doing some cloud studies. I said, “You know, the cool thing is you go out there and you might have a really dramatic configuration and you’ll start painting and look up 5 minutes later and it’s gone (laughter) – you can’t capture it, so how do you capture the essence of what it is? – so, back to influence – from abstract expressionism as kind of a starting point – Turner, for example – the phenomenon of weather – the idea that the weather in his paintings is based on observation but also really an invention. He’s taking things that he’s observed and he’s putting them into his world so that they become dramatic, otherworldly and visionary. Also in Turner – and this goes back to the Hudson River painters – is the notion of the epic scale of the landscape in relation to the individual – how we become miniscule in relation to the world that’s being depicted. People ask me, “Do you paint from a photograph?” and they often assume that. Or, “Do you paint from an airplane?” “Are you using satellite photos?” And the answer is no. I take photos because I want to remember a place in terms of what was there, but I don’t ever use a photograph as a template or work by looking back and referring to a photograph directly, and I don’t use satellite imagery, but what I do is manipulate perspective to create that aerial view, that distance, and it’s a purely invented perspective. JK: Is one of the things you’re getting from that photograph is the emotion of a place? PG: Not so much the emotion because I feel like I’ve internalized the emotion by being there and doing studies from observation. There is a tension from the depiction that I create and where it might be in the world. So the color I use is more about light than it is about literal transcription, and I think then its starts to elicit certain questions. The forms in my work, the scars and the roads etched into the land could be man made, they could be mining or they could be natural erosion but the thing about drawing is that’s it’s not really just a transcription, it’s highly selective. There’s so much information in the world that when you draw, it’s very different from photography. It’s picking out certain important things, and it’s also engaging the imagination. I think what you don’t describe, what you leave open to the imagination becomes part of a drawing but also part of the painting, too. It’s like poetry: you give a certain amount of essential information, but the reader, then, brings his own experience to the work and then things sort of take off. JK: People like Robert Motherwell, for example, were interested in exploring the emotional content of a line. Is that part of how you see your experience of creating a painting? PG: A line definitely has a character to it. Lines, for one thing can really structure space. They zigzag back, in terms of my aerial views, and lines, on their own terms can be very delicate and elegant, almost fragile when seen from a distance. So, I guess in some ways I am interested in the old-fashioned notion of beauty and transcendence. That links me with the whole tradition of painters up through modernism. For example, when you play music there has to be some sort of gratification or some sense of being transported – and that’s hard to explain – but it’s sort of a felt relationship to the material and the making of something. I studied music for a time in college, but I never listened to music early on when I painted because I thought it was too emotional and kind of distracting, and I don’t want to be sentimental or anything like that. But I started listening to Italian opera in the last few years. Its very melodramatic, and the story can be silly. But the music makes it all make sense on a much deeper level. JK: Since we’re talking about opera, and drama, let me ask you a related question. In drama of course, there’s always a tension that’s being set up. Is there a tension in your paintings that you’re deliberately setting up? PG: Well, there’s a tension between the depiction that I create and the source of where it might have been in the world. So, the colors that I use are not literal. I use color as a kind of light but also as an abstraction to create a feeling. When every painting is green in the landscape, and then the sky is blue, there’s a kind of familiarity to it, but I flip those things around, and color becomes more about light than it is about a literal transcription, and I think then it starts to elicit certain questions. The forms in my work could be could be natural or they could be part of road building, they could be mining, they could be the result of natural erosion – those kinds of questions, the kind of tensions that those things bring up are definitely a part of what my work is about. “What is this?” “Who are we?” “What is our place in the world?” I think by creating this kind of a distance between the viewer, which is a physical distance of the aerial perspective, just this kind of epic scale of the painting in terms of what I’m depicting, makes us think, or ponder, or re-examine our place in the world. “Are we a part of nature?” How do we fit into the scheme of things?” Those are basic questions, and nothing original to me, but it’s something I definitely think about. I’ve just been reading the book Endurance about the Shackleton expedition. It’s fascinating. Traveling in those little boats or camping on ice for more than a year in freezing weather on these little floating islands. And then there is no sign of anything man-made, and it’s forbidding and yet it’s beautiful – anyway, that’s something that’s very appealing to me. And I think those austere landscapes of southern Utah or the canyonlands have that same kind of austerity that is both beautiful and forbidding. It goes back to the whole notion of wilderness too – of something that’s inhospitable, even terrifying on some level – and then our imprint on that plays into that whole question of “What is wilderness?” or “What is our role in nature?” “What has culture, technology and consumerism done to reshape our place in the natural world?” JK: In some of your more industrial paintings, you can’t necessarily see it but you know there’s a lot of action going on – pollution and environmental damage and degradation, you’re also inscribing another type of terror into the landscape. Is that right? PG: Sarah Luria has called it the “toxic sublime.” That’s a little over the top in terms of the way I’d characterize most of my work, but in the extreme there is something like that when you look at the devastation on the tar sands in Canada. I did do a painting “Sands” – actually, that’s a painting I had in the gallery and I brought back to the studio…I just didn’t like it, and I thought “I’m going to repaint this,” and I started to try and fix it, and it was just dying a slow death, and I thought, “You know what? I’m just going to tear into this thing.” I had been looking at those images of tar sands. And I thought, “I can envision this. I know what this looks like.” And I started just pushing paint across the painting like a bulldozer and reconfiguring the land, and using these kind of earthy, bloody colors, plowing through, and that’s what came out of that. I would say (that painting) is really one of the landscapes that has been more radically reconfigured. For me that is a terrifying place. Emmett Gowin is a very interesting photographer and he did these photographs of the Northwest, and also of Nevada bomb test sites and the Hanford nuclear site, and he did Umatilla, OR, the weapons disposal site – and they’re all back-and-white. There’s also a strip mine called “The Black Triangle” in Czechoslovakia and it has one of the highest cancer rates in the world. It’s sort of a throwaway landscape – once you get the coal out and you’ve ripped up the Earth, you could probably go in and at great expense cover it up, you know, but essentially the attitude is that the Earth is a disposable resource. JK: When you’re working on a painting, how conscious are you of the audience or the viewer? How aware are you of all the elements and how they’re going to work for somebody else? PG: Honestly, I don’t think about that. I know that might sound strange. I kind of have this mythical audience that I’m painting to, and when it arrives at a point for me – and I’m obviously the person making the determination of when it’s finished – but for me, there a sense that it transcends my expectations and my understanding and creates a sense of strangeness, an unfamiliarity, as if almost someone else authored it. I really want to paint myself out of the painting. It’s not about me. I want it to be universal. Yet, I think that if I arrive at that point where it kind of has a life of its own – its own personality and a presence that is really compelling – I think then that the audience, a certain audience will be there for it. JK: It appears that you’re interested in placing yourself in a particular kind of relation to your materials; that you have to reach a certain sense of yourself in order to proceed with the act of painting, is that true? Or is it that doing the work puts you into that mindset? PG: Yes, I think it’s clearly the latter. Going into the studio, you can’t ever predict the day something good is going to happen. I work in the mornings, and I’m casting about, and something comes out of it usually when I least expect it. There is intention, but there is also risk. And I think art at its best, on some level embodies that. Painting somehow stimulates the imagination to bring us to a greater understanding. JK: Is there something about living in the Northwest in a certain cultural milieu that influences your thinking or your work? PG: Obviously, Seattle is a very “green” city and the University of Washington has a strong environmental profile, so I think there’s a kind of environmental consciousness here. I’ve had interactions here with a lot of colleagues with similar interests. So, I think in that sense it’s created a fertile environment for my thinking. But also because of the physical environment here – just the other day I was going through the Cascade Mountains – and because of that you’re reminded in a way that you might not be if you were living in other places. I was flying back from southern Oregon recently, and looking down and it looks like farmland. There’s a checkerboard pattern from the clear-cutting of the forest. And then there are the things that we may see directly like the affects of climate change. A forest that is diseased may have a different color from above, and be strangely alluring seen from a distance. But this is something that’s constantly in my mind. JK: What is your relationship to environmental art? PG: I respect people who call themselves environmental artists, but I don’t consider myself one of them. I don’t say, okay, I’m going to depict this devastated landscape. I would like my paintings to be more of a question mark than a declaration of some kind of position. And I guess I’m within this American tradition that celebrates beauty in the landscape, which may sound contradictory. If you go back to the Hudson River School, they had this idea of the sacred in nature. I’m not a particularly religious person, but I do think on some level painting is a spiritual pursuit; even in Rothko there is something mystical and reverential, and I do see my work that way but configured around landscape. I mean, there’s almost a sense of grief and desperation in Rothko’s late paintings, but also beauty in the paintings near the end of his life. If my paintings impart a feeling of joy, wonder or exhilaration – or something unsettling or disturbing, that’s fine – I don’t really have a specific narrative of guilt or condemnation or reproval that I want to impart. But if people come to these and they say, “Oh God, this really makes me think of strip mining” and, you know, whatever…whatever they think is fine. JK: You just started getting interested in geography in the past six or seven years? PG: Yeah, you know it was always there in a way that I hadn’t ever realized, and I must say that the Geography and Humanities Symposium at the University of Virginia where we met was wonderful in that so many different people from so many different areas came together. I think just the interconnections between different disciplines and how they map human activity in relation to the physical landscape made me start thinking a little bit more broadly about our place in the world. Jim Ketchum Jim Ketchum is a geographer and Senior Writer at Island Press. He co-edited the book, GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place 29 31 30 Trails, oil on canvas, 24” x 57”, 2006 Excavation #3, oil on canvas, 44” x 78”, 2010 Tundra, oil on canvas, 19” x 80”, 2010 35 34 Sands, oil on canvas, 52” x 41”, 2013 Project #3, oil on canvas, 59” x 56”, 2011 37 36 Excavation #2, oil on canvas, 63” x 55”, 2009 Project, oil on canvas, 47” x 65”, 2009 39 38 Squall, oil on canvas, 47” x 47”, 2010 Squall, oil on canvas, 52” x 55”, 2011 Education 1984 1980 Selected Group Exhibitions MFA, Tyler School of Art/Temple University, Philadelphia, PA BFA, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA Academic Position Professor, University of Washington, Seattle, WA Awards and Grants 40 2012 2010 2009 2008 2007 2003-6 2003 1993-4 1994 1991 1988 1987 1983-4 1972-3 Milliman Award for Association of American Geographers Presentation, New York Milliman Award for AAG Presentation and Exhibition, Seattle RRF Scholar Grant (U.W.) for Prehistoric and Post-Apocalyptic Landscape NEA grant for Northwest Art/ Northwest Environment Exhibition collaboration Milliman Award for exhibition catalog for solo show at Francine Seders Gallery Freimuth Travel Award for AAG symposium at the University of Virginia Jack and Grace Pruzan Faculty Fellowship, University of Washington Royalty Research Fund (U. W.), RRF Scholar Grant for “Duwamish Series” National Endowment for the Arts, Visual Artist Fellowship Grant, Washington DC Graduate School Research Fund, Summer Award The Pollack-Krasner Foundation, New York, Grant in Painting, February Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, Fellowship in Visual Arts, Full Award Tobeleah Wecschler Annual Award, Annual Awards Painting Exhibition Cheltenham Art Center, Cheltenham, PA Russell Conwell Fellowship, Temple University Honor Student Scholarship, College of Idaho Solo Exhibitions 2013 2011 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2002 2001 2000 1997 1996 1995 1994 1992 1991 1988 1984 City, oil on canvas, 37” x 72”, 2011 Distant Places, Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle, WA (two-person) Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle, WA Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle, WA Pierce College Art Gallery, Lakewood, WA Hampshire College, Amherst, MA Davis and Cline Gallery, Ashland OR Associazione Culturale Il Granarone, Calcata, Italy Francine Seders Gallery, Paintings from the Duwamish, Outside Time and Place Bickett Gallery, “Places: Seen and Remembered”, Raleigh, NC. The Painting Center, New York Recent Paintings, Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle Paintings, Pierce College, Lakewood, WA Outside In, Works on Paper, Francine Seders Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle d. p. Fong Galleries, San Jose, CA Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle Paul Cava Gallery, Philadelphia The Untitled Gallery, San Francisco, July Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Morris Gallery Paul Cava Gallery, Philadelphia La Galleria Temple, Rome, Italy 2013 2012 2011 2010/11 2010 2009/10 2009 2008 2007 2006 2006 2005 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987 1986 Koplin del Rio Gallery, Los Angeles, I-5 Connects Bellevue College, Bellevue, WA, Gallery Space, artists from Prographica Gallery Francine Seders Gallery, Gallery Artists, Seattle, WA Prographica Fine Works on Paper, Seattle, Commentaries: Artists respond to the Land Prographica Fine Works on Paper, Seattle, “Landscape Part II: Urban and Rural” Pritchard Art Gallery, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID. Uncommon River Prographica Fine Works on Paper, Seattle Critical Messages: Contemporary Northwest Artists on the Environment Western Gallery, Western Washington University, Bellingham Hallie Ford Museum, August-October, Willamette University, Salem, Oregon Boise Art Museum, ID Prographica Fine Works on Paper Gallery, Inaugural exhibition, Seattle Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Representing Abstraction Evergreen State College, Landscape Visions Jenkins Johnson Gallery, New York, On Paper Koplin del Rio Gallery, Los Angeles, Drawings VIII: West Coast Drawings Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle, Works on Paper University of Virginia, Geography and Humanities Symposium Exhibition Seattle Municipal Tower Gallery Space, “Structure: Art Inspired by the Built Environment” City of Seattle, Recent Purchases The Rainier Club, selected gallery artists for Seders Gallery, Seattle Seattle Academy of the Fine Arts, UW Painting faculty Davis & Cline Gallery, Ashland. OR Francine Seders Gallery. New… Idea Material Process Cancer Lifeline, Seattle, WA Francine Seders 35-year Anniversary Exhibition. (Seders private collection) The Painting Center, Winter Show, New York Francine Seders Gallery, En Plein Air Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle, Painting and Sculpture Rome Selection, Temple Gallery, Philadelphia, P.A. Drawings by Gallery Artists, Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle Davis/McClain Gallery, Gallery Artists, Houston, TX Mostra dei Docenti Temple University Rome Gallery Francine Seders Gallery, Four Abstract Painters, Seattle Paul Cava Gallery, Philadelphia Paul Cava Gallery, Philadelphia University of Washington, School of Art Gallery, Visiting Artist Exhibition Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, David Hammons Performance Collaboration, “Higher Goals.” Paul Cava Gallery, Inaugural Exhibition Tyler School of Art in Rome, Americans in Rome Carnegie Mellon Art Gallery, Pittsburgh, Perspectives from Pennsylvania Johnstown Art Museum, Johnstown, PA; Blair Art Museum, Hollidaysburg, PA (Show of 1988 recipients of Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Fellowship) “Philadelphia Fellowships, Levy Gallery for the Arts (Moore College of Art) Paul Cava Gallery, Philadelphia, April Paul Cava Gallery, Philadelphia, Drawings Mellon Bank, Founders’ Suite. Fleisher Art Memorial Challenge Exhibition Finalists Annual Awards Painting Exhibition, Cheltenham PA Art Center Paul Cava Gallery, Philadelphia, Works on Paper by selected artists 41 Visiting Artist/ Lectures/Panels/Residency 2013 Introduction to my work, University of Washington, Northwest Regional Conference in the Environmental Humanities: “The Future of the Environmental Humanities: Research, Pedagogies, Institutions, and Publics”, Nov. 3 42 University of Idaho, Moscow, Visiting Artist Lecture in conjunction with Pritchard Art Gallery exhibition Uncommon River, April 2012 Association of American Geographers paper presentation, “Evolving Interpretations of Wilderness”, New York, February 2011 Association of American Geographers paper presentation, “Art and the Politics of Landscape”, April 2009 Representing Abstraction, Museum of Northwest Art, panel discussion, October 2007 Guest Artist/Critic, Temple University Rome, December Public lecture “Altered Landscapes”, UW Rome Center, December Geography and Humanities Symposium, University of Virginia and Monticello, paper presentation “Altered Landscapes”, Sponsored by the Association of American Geographers, U. VA, and the American Council of Learned Societies, June Center for Land Use Interpretation, Invited to use Wendover, UT residency facilities for a week in May 2004 Discussion, CAA Seattle, Feb. Artist Lecture, Western Washington University, Bellingham, February 2002 Panel Discussion, Francine Seders Gallery, “New… Idea, Material Process” Francine Seders Gallery, August University of Oregon, Visiting Artist 1994 Tyler School of Art in Rome, Guest Artist/Critic, November 1992 University of Oregon, Eugene, Visiting Artist, December 3 1991 Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, March University of Washington, Seattle, “Tyler Abroad: Rome... A Studio Experience.” Slide lecture & graduate critique, February 1990 Rhode Island School of Design, European Honors Program in Rome, Guest Artist/Critic April, 1986 Moore College of Art, Philadelphia, November Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, March Selected Bibliography 2012 School of Art Newsletter, Geography and Art, October 2 http://art.washington.edu/news-events/newsletters/oct2012-art-nature/ Moscow-Pullman Daily News, “An imaginary world of rivers and industry, Philip Govedare’s landscape paintings featured in Prichard Art Gallery”, March 22 SHFT The Culture of Today’s Environment, Aerial Landscapes by Philip Govedare, January 4, http://www.shft.com/reading/ aerial-landscapes-by-philip-govedare/ 2011 Crosscut.com, Spectacular Questions: the Paintings of Philip Govedare, June 1 http://crosscut.com/2011/06/01/arts/20963/ Spectacular-questions:-The-paintings-of-Philip-Govedare/ NY Times Opinion Page, Opinionator, The Triumph of the Humanities, Stanley Fish’s blog reviews Geohumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place, June 13 http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/06/13/the-triumph-of-the-humanities/. Geography interacting with Humanities, AAG Annals, flagship journal for the Association of American Geographers, Geohumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place, http://www.aag.org/galleries/newsletter-files/Nov_NL_2010_ REVISED.pdf Geohumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place, my essay “Altered Landscapes” and painting reproduced in a book published by Routledge for the Association of American Geographers, April 2006 Hampshire College, Amherst, MA, Visiting Artist, September The Boise Weekly, Beauty and the Beast: Northwest Environmental Art at BAM University of Washington Environmental Program, Panel Discussion, “Artists Eyes: Revealing the Power of Nature’s Inspiration, April Northwest artists gather for Critical Messages, by Christopher Schnoor, February 11 “Art as Social Document”, Panel Discussion, Sponsored by the UW photography program, February 2005 Temple University Rome, Visiting Artist Lecture, September Olympic College, Bremerton, WA April Chair, “Nature in Crisis: Landscape in the 21st Century”, Panel 2010 The Boise Weekly, Critical Messages, by Josh Gross, review of group exhibition Critical Messages: Contemporary Northwest Artists on the Environment, December 15 Crosscut.com, Northwest Artists Wrestle with Environmental Threats, by Bill Simmons, review of Critical Messages: Contemporary Northwest Artists on the Environment, May 11 Critical Messages: Contemporary Northwest Artists on the Environment, catalog with essay by William Dietrich 2009 Seattle Times, Abstract, Representational combine in satisfying show in La Conner, by Nancy Worssam, “Representing Abstraction” at the Museum of Northwest Art, October 30 West Coast Drawings: Drawings VIII catalog, Koplin Del Rio Gallery, Los Angeles, by Alison Gibson, September 2008 From Above, solo exhibition (Francine Seders Gallery) catalog and essay by poet David Rigsbee, May 2006 The Valley Advocate, Amherst, MA, “Unedited Landscape”, September 28 Daily Hampshire Gazette, Amherst, MA, “Painter Depicts Landscapes Laid Waste by Humanity”, September 19 2005 Civita Castellana, In Mostra I Quadri di Govedare, August 2004 The Seattle Weekly “Visual Arts Pick”, Review of solo show, “Duwamish Series. Outside Time and Place” by Andrew Engelson, October 20-26 The Stranger, Liminal Landscapes, Known and Unknown Worlds, (review of solo exhibition at Francine Seders Gallery by Katie Kurtz), October 14 Duwamish Series, Outside Time and Place, catalog essay by Charles D’Ambrosio 1991 Philadelphia Inquirer, review of solo exhibition at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts Morris Gallery, February 17 1989 New Art Examiner, review of “Perspectives from Pennsylvania,” Carnegie Mellon Gallery Pittsburgh (drawing reproduced), November Hard Choices, Just Rewards, catalog for traveling exhibition of Pennsylvania, Carnegie Mellon Gallery, Pittsburgh (drawing reproduced), November Philadelphia Inquirer, review Cava Gallery Group Show, April 1988 Philadelphia Inquirer, “Govedare’s Abstract Art,” review of one-person show at Cava Gallery March 1987 Philadelphia Inquirer, review of Cheltenham Annual Awards Exhibition, Philadelphia, March 1986 Philadelphia Inquirer, review of Cava Gallery Works on Paper Show, June Selected Collections Coventry Financial, Philadelphia 2008 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, review of panel presentations (Landscape: Nature in Crisis) at CAA conference, February Russell Investment Group, New York Office 2006 NYFA Current. Article on “Nature in Crisis: Landscape in the 21st Century” panel. Discussion Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA 2005 1999 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “Like a Breath of Fresh Air”, review of En Plein Air, Francine Seders Gallery The Gloston Associates, Seattle, WA, 2004 1997 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “Modernist Says Much Without Saying a Word,” Nov. 14 1995 Seattle Times, review of solo exhibition at Francine Seders Gallery, May 11 1992 Philadelphia Inquirer, review of solo exhibition at Paul Cava Gallery, Philadelphia, May 28 Seattle Public Utilities Portable Works Collection 2005 Dean Standish Perkins & Associates, Seattle, WA 2004 University Club, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2004 Zevenbergen Capital, Seattle, WA, 2000 Washington State’s Art in Public Places Program, Kent School District Portable Collection 1995 Federal Reserve Bank, Philadelphia, PA, 1989 Prudential Insurance Company, Philadelphia, PA, 1988 43 44 Wetlands, ink on paper, 18” x 12”, 2008