Food Marketing in Western Europe Today

advertisement

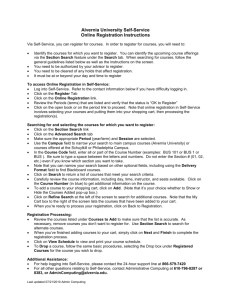

Food Marketing in Western Europe Today JOHN C. ABBOTT DECISIONS of Safeway, Inc., to open supermarkets in I^HE • Britain is an indication of the interest in the revolution in food marketing now going on in Western Europe. Any doubts about self-service and acceptance of prepackaged and other convenience foods which supposedly dominated food traders' ideas as late as 1957 have now been dispelled. Among the new developments are self-service retailing, one-stop shopping, prewrapped food in convenient-sized units, and the use of canning and freezing to make previously perishable foods continuously available. These new methods have led to changes in marketing structure, both at the retail and wholesale level. They also have important implications for the marketing of food products from farms. Self-Service Retailing The advantages of self-service retailing are greatest where the time of both customer and retail shop employee is highly valued. The first European countries to have several self-service shops were Britain, Sweden, and Switzerland. As Table 1 shows, this growth has been especially rapid since 1956; and in most countries it still continues. In Sweden, however, with one self-service shop per 1,560 people, development in terms of numbers may be approaching a maximum. TABLE 1 GROWTH IN SELF-SERVICE FOOD STORES" Number of i^elf-service food stores Coimtry Food trade In Europe Is undergoing many changes; and both retailers and investors seem to be getting confidence in self-service supermarkets, prepackaging, frozen foods, and similar developments. But what about public opinion? What about suitable suppliers and managers? This article gives some answers to these and related questions. VJJf8 Austria Belgium Britain Denmark Prance West Germany Ireland Netherlands Norway Spain Sweden Switzerland 3 130 1 1 2 1956 1961 40 120 3,000 375 603 1,380 3 510 1,100 1,480 570 9,000 1,600 2,700 30,680 150 2,860 1,650 450 22 5 3,000 900 6,000 2,000 ''Sources: The Economic Perform^ance of Self-Service in Europe (Paris: Organization for European Economic Cooperation, 1960), p. 16; K. H. Henksmeior "The Situation of Self-Service in Europe," Self Sirvice 1961 (Cologne: International Self-Service Organization, 1962), p. 5. 17 18 Journal of Marketing, April, 1963 A more significant measure of growth is the proportion that self-service sales constitute of total retail food sales. Estimates for four countries are shown in Table 2. Usually the most active food retailing, firms such as the Migros cooperative in Switzerland are almost entirely self-service. That the overall proportion of self-service stores is not higher in such countries is attributed to lack of opportunity rather than unwillingness to change. Many of the existing stores are too small to be converted, or conversion would cost too much. They are likely to continue on rather uneconomic lines until the present operators retire; then they will be amalgamated into larger units or disappear. As an example, one forecast is that the present 24,000 grocery stores in the Netherlands will be replaced in the next few years by some 8,000 small and 1,500 larger self-service stores, and 500 supermarkets.^ Supermarkets Formerly a housewife desiring to buy bread, sugar, salt, eggs, meat, fish, fruit, vegetables, and wine might have to go to many different stores. In Italy, for example, there are different outlets for four kinds of meat; and in each the customer must wait for service, pay a bill, and have a separate package made up. The development of the supermarket in such countries means that the whole range of food can be obtained on one set of premises, and paid for at one time at one checkout stand. A supermarket sells a full range of foods, including fresh vegetables, dairy products, meat, and fish, plus cleaning materials and other nonfood items in daily household use; sometimes fresh meat is sold separately on a concession basis. The store should also be of a certain size—4,000 square feet is the minimum agreed upon by the International SelfService Institute of Cologne. In the above sense, there are now some 160 supermarkets in Italy, 100 in France, several hundred in Germany, 50 in the Netherlands, and 35 to 40 in Switzerland. The 700 reported for Britain include some of only 2,000 square feet. The pace of development has quickened markedly in the last two years. By 1965, there probably will be 3,000 supermarkets in France. At the current rate of opening, approximately 300 new supermarkets will be added in Britain this year. The former mood of cautious experimentation has led to one of competition for the best available sites. For the leading firms, the opening of new supermarkets has become a fairly standardized process which can be repeated (with local variations) as fast as permission, building dates, and capital will allow. p . L. Van Muiswinkel, quoted in The Financial Times, London, August 23, 1961, p. 5. TABLES 2 SELF-SERVJ CB FOOD SALES AS PEECENTAGES OF TOTAL BY RETAIL VALUE' Country Year % Britain West Germany Netherlands Switzerland 1961 1961 1960 1958 15.5 40.0 32.0 22.0 * Sources: Britain—Self-Service Development Association, London, personal communication, January 8, 1962; Germany—H.K. Henksmeier "The Situation of Self-Service in Europe," Self-Service 1961 (Cologne: Intemational Self-Service Organization, 1962), p. 11; Netherlands—Vereniging van Zelfbedienings Bedrijven, Arnhem, personal communication, December 11, 1961; Switzerland—The Economic Performance of Self-Serviee in Europe, (Paris, Organization for European Economic Cooperation, 1960), p. 23. Opening of New Food Retail Outlets How far has the shift to self-service and supermarket retailing affected the parts played by different kinds of enterprises in the food trade? Inevitably initiative in adopting new methods and ability to obtain the necessary finance has varied— see Table 3. In 1961, 72% of the self-service retail food outlets in the Netherlands were owned by independent retailers, 23% by chains and department stores, and 5% by consumer cooperatives. The corresponding percentages for Britain were: independent retailers, 21%; consumer cooperatives, 43%; chains and department stores, 36%. Here the cooperatives were the first to take up self-service on a large scale; and this has helped them to maintain their share of the retail food trade. Initiative in the establishment of large supermarkets has come in Britain mainly from outside the grocery trade—from a Canadian biscuit and bread manufacturer, a large milk chain, and a department store group. In Italy, three-quarters of the new supermarkets have been set up by retail chains like Rinascente-Upim and Standa, which were already experienced in the organization of mass distribution but not previously very active in the food trade. The biggest supermarkets firm in France is controlled by the Brussels department store • ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Engaged first in marketing research and advisory work at the Agricultural Economics Research Institute, Oxford University, and then at the University of California, John C. Abbott is now Chief of the Markefing Branch of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. He received his M.A. from Cambridge University (England) and his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley. He is author of MARKETING PROBLEMS A N D IMPROVEMENT PROGRAMS (Rome, Food and Agriculture Organiiation, I95S) and other publications on international marketing. 19 Food Marketing in Western Europe Today TYPES OP RETAIL Country Britain Prance West Germany Netherlands Switzerland TABLE 3 FOOD STORES AND SELF-SERVICE" Multiple and department stores % selfYear Total service 1961 16,000 21 1961 25,600 7 1961 7,200 53 1961 1,280 50 1960/61 1,241 5 Consumer cooperatives % self% selfservice service Total 2 13,000 30 0.4 8,000 0.3 39 16 9,650 9 900 16 6 4,180 28 Independents Total 200,000 155,000 150,000 22,000 17,140 " Source: Computed from numbers of self-service food stores of different types reported for December 31, 1961, by K. H. Henksmeier in "The Situation of Self-Service in Europe," Self-Service 1961, (Cologne: International Self-Service Organization, 1962), p. 10, and most recent estimates of total numbers of food stores of different types —for Britain, France, and Germany The Economic Performance of Self-Service in Europe (Paris, Organization for European Economic Cooperation, 1960), p. 27; for Netherlands, as supplied by the Vereniging Van Zelfbedienings Bedrijven Arnhem in a personal communication, December 11, 1961; for Switzerland as reported by SWEDA Registrierkassen, in Die Selbsbedienung im Schweizer Lebensmittelkandel (Zurich, 1962), 4 pp. rinnovation. In Spain, the first 50 supermarkets were set up by the government. Insurance companies now recognize a supermarket building as a sound investment for long-term capital. The main problem is to find competent managers; and prior experience in a grocery store of the traditional counter-service type is not an adequate qualification. Following a trial-and-error approach, some of the Italian firms opening supermarkets have appointed and replaced a number of managers before finding men who could meet their requirements. Weston in Britain has brought in experienced Canadians to help start up the new supermarkets, and a number of the chains have started special training courses.^ Prepackaging Food for self-service counters is usually packaged in containers that simplify wholesale and retail handling. The vital self-selling functions which the package then acquires are becoming fully recognized in Western Europe. Packaging of durable groceries such as sugar, tea, dried peas and beans, and rice in units convenient for the average retail purchase has been common practice for some time. By 1956, prepacked foods amounted to one-half or two-thirds of total food purchases in Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Norway, and one-quarter in Italy. The prepackaging of fresh foods^meat, fruit, vegetables, and cheese—has been helped by the improved transparent plastic wraps now available. However, these foods must be packaged only a short while before sale to the consumer if they are to retain quality and appearance. '^ The Financial Times, London, October 27, 19(;2, p. 10. Canned Foods Display of a wide range of canned meats, fruits, juices, vegetables, and soups is a feature of selfservice retailing in Europe. Imports have long been available in quantity from the United States, Australia, South Africa, and South America. An increasing volume is now being canned in Europe. In 1960, 622,000 tons of canned vegetables were sold in Britain and 367,000 tons of canned fruit. In the rest of Europe, however, canned food consumption has not approached the per capita levels in the United States. See Table 4. Perhaps the fastest growth in canning, can be expected in Italy, where large- scale operations have been confined mainly to peeled tomatoes and tomato paste. With more advanced can-making equipment and the entry of firms from the United States and from other parts of Europe, the canning of other vegetables, fruits, and juices began to increase rapidly in 1961. TABLE 4 PER CAPITA CONSUMPTION OF CANNED FOOD IN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES AS A PERCENTAGE OF THAT I N THE UNITED STATES ( 1 9 6 0 ) " Fruit Vege- Fruit tables Milk Britain Belgium Denmark France West Germany Netherlands Fish Meat juice 76 75 33 40 94 15 33 41 42 63 18 4 6 17 27 35 5 22 47 32 29 50 18 88 50 41 3 13 26 127 30 55 n.a. 30 21 " Source: The Financial 1961), p. 6. Times, London (April 4, 20 Journal of Marketing, April, 1963 Frozen Foods Judging by the commercial activity in frozen food distribution in Northern Europe, a still more rapid expansion is anticipated in this field than in sales of canned food. The current European output of 300,000 tons of frozen foods per year is expected to reach 1.7 million tons by 1970. Annual per capita consumption of frozen foods in Sweden is 7 pounds as compared with 40 pounds in the United States; Britain comes next with 6 pounds; and the Western European average is only 2 pounds. At present the frozen-food industry is dominated by a few large firms. In Britain, for example, Unilever's Birds Eye brand has two-thirds of the market, and Findus (now owned by Nestle) and Associated Fisheries, one-tenth each. The increasing trend to combine the marketing of frozen fish and poultry suggests that chicken, turkey, and tuna fish will become direct substitutes and competitors in Europe as in America. More than one-fifth of the food retailers in Germany had freezer cabinets in 1960. It is estimated that some 90,000 retail outlets are equipped to sell frozen food in Britain, but the cabinets are not large enough to hold the full lines of several competing brands. This results in high-pressure wholesaling and extra allowances to retailers, thus bringing their margins above the usual 20%. The need for an uninterrupted refrigerated channel of distribution from processor to consumer is particularly marked in countries such as Italy and Spain, with very hot summers. High investment costs and doubts as to consumer acceptance of frozen foods have slowed down development. However, the refrigeration equipment industry in Europe is now growing out of the experimental stage; with large-scale operation and increasing, competition, purchase costs are tending downward. New outlets for frozen foods in Northern Europe are hotels, restaurants, and institutions providing group meals. In the past, prices of frozen food were thought too high for this market; but they are now being accepted, as costs of labor and handling of other foods rise. There is also interest in automatic vending machines because of their potential appeal in countries where late evening and Sunday opening of food stores is rare.* Convenience foods absorbed 18 to 19% of household expenditure on food by average income families in Britain in I960.* Complete frozen dinners and dehydrated.meals are now on sale; and sliced 3 For example, comment by J. R. Parratt, Chairman of Bird's Eye Foods Ltd. reported in The Times, London, September 25, 1&59, p. 4. * Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Domestic Food Consumption and Expenditure: 1960 (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1962), p. 44. bread and cheese, prepared sweets, jellies, custards, and instant puddings are becoming standard retail items. Standardization and Continuity of Supplies For successful self-service supermarket retailing, there must be easy access to large and regular supplies of produce of uniform type, quality, and size. But it is difficult to obtain these conveniently from small distributors or municipal markets which are characteristic sources of wholesale supplies in many parts of Europe. The Rinascente-Upim group found this a major obstacle in undertaking supermarket retailing in Italy—^the only dependable supply sources were in other countries. With 400 retail outlets in Britain, Marks & Spencer was unable to take up a number of food lines because of difficulty in controlling quality standards, particularly of imported products. Suppliers of food for sale under its brand name have been induced to invest over $16 million in specialized inspection equipment and personnel over the three years 1959-61. Recently some of the major European food marketing firms were approached for funds to finance the coordination of existing food standards through the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and through the Codex Alimentarius (Vienna). The first firm contacted immediately oifered twice the sum needed. Ability to obtain supplies consistent in type, quality, and form is also influenced by import controls, tariffs, and subsidies which protect domestic sources (both farm and trade) against outside competition, and reduce willingness to adapt to new ways of marketing. Entry of imported foods may be cut off abruptly when the price of the home-produced item falls below a certain level (for example, meat, including processed and canned meats in Germany and Italy), or when home produce comes onto the market in a certain volume (for example, Britain and France for fruit and vegetables). Advertising Limited personal contact with the self-service shopper makes effective advertising all important. The big issue in Europe now is whose brand is put before the public—^that of the processor wholesaler or that of the retailer. Processor advertising of packaged foods offered for sale on a standard country-wide basis is favored in Europe by national rather than local radio and television programs and newspapers. Brand promotion is especially strong with convenience foods, such as soups, beans, and cooked meats. In Britain, nearly $3 million was spent in 1960 on the television promotion of wrapped and branded Food Marketing in Western Europe Today bread."' Independent retailers and the managers of small chains are generally pleased to go along with this system, because it ensures that the goods they stock are well known to the public. The large retail chain or a firm with a number of supermarkets has more to gain by putting forward its own brand; it buys and sells enough to justify the promotion cost; and it can then offer something which is not available in the stores of rivals and can set its own price. Thus, Marks & Spencer in Britain prefers to contract with smaller firms for .supplies which will carry its own brand name; and Victor Value, with 30 to 40 supermarkets, is sponsoring its own Dairyglen brand of butter. Wholesale Purchasing and Supply The supermarket retailer wants to obtain supplies regularly and easily in large standardized lots, conveniently and economically packaged, with clear identification to the consumer. In meeting these requirements, substantial economies are attainable with size. In Britain, which imports over half its food supply, wholesale distribution has long been carried out by relatively fewer and larger firms than in Europe as a whole. The Cooperative Wholesale Society is one of the world's biggest food buyers, distributing to affiliated outlets almost one-quarter of all the food consumed. Further large blocks of retail food outlets are supplied by the central wholesale buying departments of large grocery chains. This contrasts sharply with the position in many other European countries where most food is produced domestically and is bought from a large number of very small farms. In France over four-fifths of the food supply is handled by 285,000 retailers buying independently. Also 150,000 grocers are supplied by over 1,000 wholesalers; and 40,000 butchers draw from 20,000 slaughterhouses. In Belgium, Germany, and Italy food has been bought wholesale from a similar structure of small suppliers. Either retailers have gone personally to buy in central markets and from small local wholesalers, or have been visited by a succession of salesmen. Retail Buying Groups The formation of retail buying groups and voluntary chains has enabled many independent retailers to take advantage of quantity discounts at wholesale. In the Netherlands 70% of the independent grocers belong to such chains and buy three-quarters of their stock through them. In Germany, the EDEKA buying group had 42,000 associated retailers in 1960, and REWE had 12,000.e De Spar, Vege, Cen•>' The Financial Times, London, June 8, 1961, p. 7. 6 The West German Market (Zurich: Contimart, 1960), p. 64. 21 tra, and vivo have branches in several European countries; and International Spar has 225 wholesale and 30,000 retail members. Much of the original impetus behind the formation of these retailer buying groups came from the wholesalers' fears of being "squeezed out" as their independent retailer customers lost business to the chains. This threat is being felt again as a new phase of intensified competition with integrated supermarkets opens. There is doubt as to whether the independence of the more loosely organized buying groups can be maintained in face of new investment and merchandising requirements. The result expected in West Germany, for instance, is the transformation of parts of these groups into corporate chains. Spar is encouraging its retailer members to set up supermarkets which though independently owned will carry its name and display material. The establishment of cash-and-carry wholesale food warehouses is another low-cost way of meeting the supply requirements of small retail grocers who cannot buy in great bulk. Buying Arrangements With Agriculture The ways by which a large wholesale processing or distributing unit can best obtain supplies from domestic agriculture with the type, form, and regularity needed are well known in Europe. Long before World War II many European farmers were being supplied with suitable varieties of sugar beet and canning pea seed on production and sales contracts requiring delivery to processing plants of specific quantities on specific days. This approach is now being applied to many mo7e agricultural products: pigs, poultry, eggs, and a wide range of fruits and vegetables, with the most striking developments in frozen broilers. The annual output of broilers in Britain has risen from 5 million birds in 1954 to an estimated 140 million in 1962. Meat-cutting, and prepacking plants are being set up in Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, and other European countries to meet the demand for large regular supplies of standard cuts. Often this results in much more profitable distribution of cuts between markets with differing demands. Towers, which prepacked and froze one million New Zealand lambs in 1961, sold the legs from one lot in Britain, the shoulders in Canada, the loins in the United States, the breasts in Ghana, and the shanks in Honolulu. Marketing Efficiency In Europe the retail phase of food marketing has always taken up a large part of the total margin between producers and consumer—for eggs, 40 to 60% and for beef, 50 to 80%. If new methods 22 Journal of Marketing, April, 1963 and organization can bring about significant savings, this will be a major advance in overall marketing efficiency. One authority maintains that the average sized supermarket in Britain achieves savings in labor over counter service amounting to 2%% of sales, a significant difference in a total margin of 17 to 18%. And against this must be set increased costs of wrapping of about 0.4%.^ Extra investment in equipment is offset by faster turnover of stock; and now that supermarkets are becoming the vogue, investment funds can be found fairly easy to finance the capital cost of the building and lease it back to the operator. Level of Competition How far the benefits of lower costs are passed on to consumers depends on the level of competition among supermarkets. During the early stages of a technological revolution this is usually considerable. The need for each new supermarket to attract a high volume of customers in order to achieve low costs constitutes a strong inducement to price-cutting. Advertisements of "special low prices" for branded goods in Britain, Germany, and other countries is evidence of willingness to do this. The general move by European governments against restrictive business practices and resale price maintenance has also helped. Experience in the United States suggests that competitive reduction of margins in Europe may W. G. McLelland, Economic Joumai, Vol. 72 (March, 1962) pp. 162-163. proceed for some time, as long in fact as the supermarkets are fighting to establish themselves against the competition of retail traders using traditional methods. Benefits to Consumers There is little doubt about the benefits brought by the supermarkets to European consumers. While food traders in France, Italy, and Switzerland, for example, conceded that self-service would permit lower retail prices, they thought that credit and other customary requirements would lead many consumers to prefer the old system. However, rising levels of income available for food purchases, and the steady increase in employed women unable to spend much time cooking and shopping, have changed the character of the "average" European consumer. With recent rises in incomes and the movement of rural populations into new suburbs, this "average consumer" now includes an increasing proportion of the French and Italians whose tastes and requirements were thought so different. In many of the northern European countries, the influences in favor of packaged ready-to-cook food have been present since the early 1940s, but only during the last four or five years have the implications for marketing been recognized. Previously retailers struggled to recruit expensive labor for time-consuming procedures; and consumers tolerated slow service, incomplete cleaning and preparation, restricted choices, and inconvenient shopping hours. Neither had realized that the postwar sellers' market was over. MARKETING MEMO What Have We Learned Frotn The Behavorial Sciences? The impact of the behavioral sciences on our society is far greater than most people realize. At one level they are providing technical solutions for important human problems. But at a deeper level they are changing, the conception of human nature— our fundamental ideas about human desires and human possibilities. When such conceptions change, society changes. In the past few generations, many beliefs about such diverse matters as intelligence, child rearing, delinquency, sex, public opinion, and the management of organizations have been greatly modified by the results of filtering scientific fact and theory through numerous layers of popularizing translation. The casual way in which unproved behavioral hypotheses often find widespread acceptance underscores the importance of strengthening and deepening the behavioral sciences and of securing better public understanding of what they are and what they are not. —"Strengthening the Behavorial Sciences," Science (April 20, 1962), pp. 233-234. Reprinted by Permission of Science.