- White Rose Etheses Online

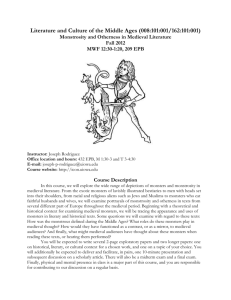

advertisement