Tendering for Government Business: process contracts, good faith

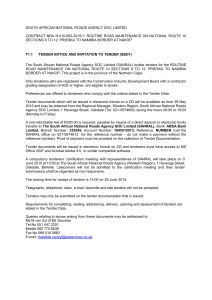

advertisement