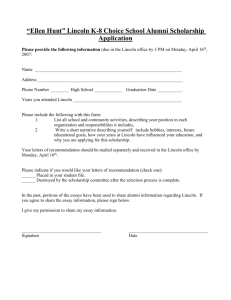

Robert L. Kincaid Endowed Research Center Essay

advertisement

The Dr. Robert L. Kincaid Endowed Research Center and the Judeo Christian Ethic in Antebellum American Political and Social Life Mission Statement: The Dr. Robert L. Kincaid Endowed Research Center promotes the scholarly study and public understanding of the influence created by the Judeo-Christian Ethic upon the era and the legacy of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln Memorial University Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum Harrogate, Tennessee May 6, 2014 1 The Dr. Robert L. Kincaid Research Center focuses primarily on the research and interpretation of the streams of moral and ethical influences in American culture during the life and leadership of Abraham Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln, a documented rationalist, never joined a religious organization but did associate with several denominations, including old-school Presbyterian. 1 Despite his enigmatic views of faith, he memorized large passages from the Bible and used them in many public and private writings. His later speeches were thick not only with Christian language but also with ideas of Providence and Divine Justice. These are concepts that informed his political policies. 2 These underlying beliefs existed in all dominant American Protestant denominations, as well as Judaism and all other branches of Christianity. The problem with many discussions of these related beliefs, which were harbingers of the JudeoChristian Ethic, is they did not result in unified practice but rather highlighted existing divisions along political and sectional positions. Primary research in this area is consistent with the missions of Lincoln Memorial University and the Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum and should make significant contributions to the body of scholarly literature. The current socio-political use of the term Judeo-Christian Ethic has endured recent changes in connotation. By common usage, Judeo-Christian Ethic has come to describe not so much a single moral code but a worldview deriving its basic moral expectations of public and private behavior from the Jewish and Christian Scriptures and teachings. The usefulness of the term largely consists of its applicability across a broad spectrum of those who share the Bible as the source of their ethics. Although the historical connection between Christianity and Judaism 1 This expression refers to the split within the Presbyterian Church in 1837. It is related to the term OldLight which indicates a church that opposed the revivals of the Great Awakening. See Richard Carwardine, “Lincoln’s Religion,” in Our Lincoln: New Perspectives on Lincoln and His World edited by Eric Foner and Ronald C. White, Jr. Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), 128-129. 2 Ronald C. White Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002). 2 dates from the time of Jesus through C.E. 70, their interrelationship has been understudied. Even within Christianity, divisions between branches often obscured shared beliefs. Nineteenth century religious thinking tended to overlook these historic connections. The term Judeo-Christian Ethic evolved in the early 20th century during ideological battles against Nazism and Communism.3 It entered common usage among Protestants because the basic term “Christian” had been co-opted by entities promoting non-Christian ethical positions and divergent political arguments. Advocates of a Christian conviction of truth used Judeo-Christian Ethic to express core beliefs common to both Jewish and Christian teachings. This term has since come to express or defend particular political and social positions favored by various Protestants rather than the literal application of Biblical teachings. For example, a large number of partisan political activists use this expression to promote the worldview known as “American Exceptionalism” (belief that the United States originated as a uniquely Christian culture and nation with a government “for the people and by the people”), and thereby defend issues such as school-sponsored prayer and Bible reading. 4 Because Judeo-Christian Ethic often carries other meanings in political and religious rhetoric, its use as an academic term must be carefully defined. As a basis for initial research and scholarship, the term Judeo-Christian Ethic is defined as a common source of core beliefs and ethics rooted in the foundations of Jewish thought and history (as codified in the Ten Commandments, Torah and other sources), upon which many tenets of Christianity, Western philosophy and political expressions are based. Participants in the Dr. Robert L. Kincaid Endowed Research Center will be encouraged to more particularly describe the Judeo-Christian 3 Mark Silk, “Notes on the Judeo-Christian Tradition in America,” American Quarterly 36, no. 1 (Spring 1984): 68. 4 Abraham Lincoln, “Address at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania,” in Abraham Lincoln: Selected Speeches and Writings, introduction by Gore Vidal (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 2009), 405. 3 Ethic as generally understood in Lincoln’s America, as well as the mutual influences between American religion and politics, which provide a rich area of exploration within early American history. Historically, religious evolution has been tied to socio-political change. In the United States, the Judeo-Christian Ethic originated from a complex fusion of different religious and cultural traditions mixing with contentious political conditions. Historian Mark Noll has noted that an evangelical Protestant theology heavily influenced political thinking in the United States. This theology was “decisively shaped by its engagement with Revolutionary and postRevolutionary America. Christianity became connected in Protestant eyes with democracy and a republican government.” 5 After the revivals of the early 19th century, Noll claims, “Protestant evangelicalism differed from the religion of the Protestant Reformation as much as sixteenthcentury Reformation Protestantism differed from the Roman Catholic theology from which it emerged.” 6 While the religious and political traditions of the United States developed differently from those of Europe, they also brought about diverse groups within the United States. The religious revivals of the 18th and early 19th centuries (particularly the Great Awakenings) had extensive political consequences for the Civil War Era of the United States. The religious/Christian influences were neither simple nor consistent. Many Americans in the Civil War Era believed in the same single source of truth but arrived at drastically different political and ethical positions. Politicians and commentators disputed those interpretations of the Bible (or portions of it) and how its authority should guide public policies. These religious/political beliefs drove most of the “sisterhood of reform” movements that split 5 Mark A. Noll, America’s God from Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (New York: Oxford University Press), 3. 6 Ibid. 4 American society along the fault line of abolitionism. 7 Serious literal readings of the Bible served both to support and to attack slavery as a social and political practice. By the 1830s, the religious discord reflected the national divisions President Lincoln outlined in his Second Inaugural Address. The Judeo-Christian Ethic rarely exerted its influences unalloyed by political or social elements. Conflicts leading to the Civil War have been debated regarding the use and importance of theological and religious thinking in partisan politics. Many current scholars focus on the nonevangelical position Lincoln held and ignore any Christian influences on Lincoln’s writings and speeches. In contrast, uncritical biographies of Lincoln’s religious views range from evangelical Protestant to an agnostic perspective. As a result, these writings have prompted the need for objective study in this subject area. The Dr. Robert L. Kincaid Endowed Research Center seeks a balance that acknowledges the diverse Christian influences on partisan politics as well as the power of popular culture and politics to impact theological positions in the various denominations. The Center invites inquiry and study from all political and religious perspectives. Projects and programs should acknowledge the mutual interaction between moral/ethical convictions and cultural/political worldviews and the profound impact of these forces on conflicting American thought leading to the Civil War and the continuing Constitutional conflicts. 7 Ronald G. Walters, American Reformers, 1815-1860 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1997) and Jean Fagan Yellin and John C. Van Horne, eds., The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994). 5 Further Readings: Carwardine, Richard J. Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1997. Goen, C. C. Broken Churches, Broken Nation: Denominational Schisms and the Coming of the Civil War. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1985. Noll, Mark A. America’s God from Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Silk, Mark. “Notes on the Judeo-Christian Tradition in America.” American Quarterly 36, no. 1 (Spring 1984): 65-85. Walters, Ronald G. American Reformers, 1815-1860. New York: Hill and Wang, 1997. White, Ronald C., Jr. Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002. Yellin, Jean Fagan and John c. Van Horne, eds. The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994. 6