Exploring New Intake Models for the Emergency Department

advertisement

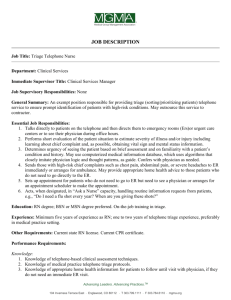

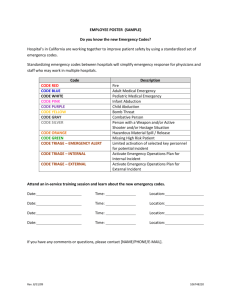

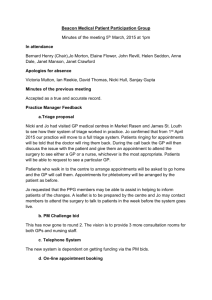

Exploring New Intake Models for the Emergency Department American Journal of Medical Quality XX(X) 1–9 © 2010 by the American College of Medical Quality Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1062860609360570 http://ajmq.sagepub.com Shari Welch, MD, FACEP,1 and Steven Davidson, MD, FACEP, MBA2 Abstract The objective of this article was to explore new intake models for processing patients into the emergency department (ED) and disseminate these new ideas. In the fall of 2008, the Board of Directors of the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) identified intake as an area of focus and asked its members to submit new intake strategies alternative to traditional triage. All EDBA members were invited to participate via an Email survey. New models could be of their own design or developed by another organization and presented with permission. In all, 25 departments provided information on intake innovations. These submissions were collated into a document that outlines some of the new models. Collaborative methodology promoted the diffusion of innovation in this organization. The results of the project are presented here as an original article that outlines some of the new and mostly unpublished work occurring to improve the intake process into the ED. Keywords quality improvement, emergency department, triage, learning community According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the modern-day emergency department (ED) is the point of entry for more than half of all patients admitted to the hospital in the United States.1 Coming through this “front door” to the hospital are over 200 visits every minute of every day in the United States, amounting to an astonishing 40 visits to the ED per 100 citizens every year. The patient visits involve complex medical issues: 43% of patients present to the ED with moderate to severe pain, almost 40% of patients wait more than an hour to see a physician, and one quarter of the patients seen in the ED spend more than 4 hours there.2 On average nationwide, 3% of patients who seek urgent health care will leave the ED without being seen by a physician because of unacceptable waits and delays.3 These figures are even higher in urban settings with highvolume EDs. Thus, ED inefficiencies and delays translate into almost 4 million patients annually walking away from health care after presenting for help. Given the complexity of the clinical setting, it should come as no surprise that The Joint Commission has found that the ED is the most common site for sentinel events in the hospital as a result of waits and delays in care.4 Timeliness of care is an issue that is front and center for EDs in the United States and the world. The dialogue about overcrowding has given way to discussions of patient flow, how to measure patient flow, and how to make improvements. Timeliness of care is among the strongest correlates with patient satisfaction,5 and particularly, the time it takes to see a physician (door-to-physician time) has the best correlation of all. By moving patients quickly to patient care areas and having the physician evaluate them in a timely fashion, patients perceive that the wait time is acceptable.6,7 As the time interval from patient arrival to the physician’s evaluation increases, the rate of patients leaving without being seen (LWBS) increases.8-10 Finally, with growing numbers of clinical entities requiring treatment that is “on the clock,” timeliness of care begins with efficient intake of patients into the ED.11-16 There is bureaucratic pressure to improve ED intake processes as well. The Joint Commission now requires hospitals to demonstrate that they track patient flow from 1 Intermountain Institute for Health Care Delivery Research, Salt Lake City, UT 2 Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose. Corresponding Author: Shari Welch, Intermountain Institute for Health Care Delivery Research, 36 South State Street, 16th Floor, Salt Lake City, UT 84111 Email:sjwelch56@aol.com 2 American Journal of Medical Quality XX(X) Table 1. Characteristics of Traditional Triage Inefficient Many repetitive steps Steps have no value to the patient Processes occur in series, not in parallel Long door-to-physician times intake into the ED through the inpatient side.17 This is in addition to the core measures established by The Joint Commission that involve tracking clinical care critical actions and timeliness for specific disease entities like acute coronary syndrome, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia. Furthermore, in October of 2008, the National Quality Forum endorsed 10 quality and performance measures for the ED.18 This was the culmination of a 3-year process that involved vetting recommendations from numerous quality organizations and technical expert panels. These 10 quality measures include 5 clinical measures and 5 operational measures, the latter including door-toprovider time and its close cousin measure LWBS. These measures are expected to form a foundation for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services pay-for-performance reimbursement plan for EDs. Traditional triage often consists of 8 or 9 steps for the patient prior to contact with the physician—steps that are often repetitive, occurring in series instead of in parallel, and add no value for the patient (Table 1, Figure 1). In this study, a quality improvement collaborative sought information on alternatives to traditional triage for dissemination to its members. Methods The Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) is a nonprofit organization comprising 140 US EDs and representing more than 5 million ED visits annually. EDBA was founded in 1997 as an alliance of performance-driven EDs. It operates as a quality improvement collaborative, sharing performance data and operational strategies to identify best practices. EDBA has developed a benchmarks database and educational program and disseminates new ideas and innovations in print and through conferences.19-26 In September of 2008, the EDBA board of directors identified intake into the ED as an area for collaborative study. An Email survey was sent to all members asking for information about new intake strategies being used or considered for trials at member organizations. All EDBA members were invited to participate, and 25 sent submissions describing new intake models. New models could be of their own design or discovered by another organization and presented with permission. Many of the submissions involved unpublished trials. The results were collated and distributed to the group. Results Table 2 summarizes some of the newer intake models being trialed around the country, much of them as yet unpublished. The table presents a compilation of the ideas, models, and innovations submitted by participating members in the EDBA intake models survey and collated for distribution to its members as a collaborative learning experience. Midlevel Provider in Triage For this alternative, the trend has been to elevate the level of education and experience of the person in triage. When midlevel providers (ie, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) are placed in triage, this change has resulted in reduced throughput time, reduced waits, and reduced rates of LWBS.27,28 Physician in Triage There are ample data to support the placement of the highest level of training at intake. Paramedics correctly predict whether or not patients will need to be admitted from the ED 62% of the time.29 In another study, Kosowsky et al30reported how reliably the nurse could predict a patient’s disposition. On the other hand, there is a growing body of evidence in the literature that demonstrates that physicians’ assessments of outcome and disposition are highly reliable, with 85% to 95% accuracy.31-34 Dedicating a physician to the intake process has a number of advantages. Studies have shown that placing a physician in triage decreases length of stay (LOS), decreases LWBS rates, and increases staff satisfaction, and that approximately one third of patients can be rapidly discharged using few or no resources.35-37 In the Triage Rapid Initial Assessment by Doctor (TRIAD) study, throughput time was decreased by 38%, with no increase in staff. In response to a census that doubled in 5 years and LWBS rates that had reached 20%, the staff at Arrowhead Memorial Hospital in California tested a physician in triage model made possible by bringing in furniture modules that created small cubicles in which physicians could examine patients. Their experience revealed that 50% of patients could be discharged right from the cubicle (Figure 2). This opened up beds and reduced nursing needs. Their LWBS dropped to 1%, and their time to see a physician, which had begun at 4 hours, was reduced to 31 minutes.38 Team Triage In 2004, a British team was among the earliest to suggest innovations, including advanced triage protocols, care teams, and multidisciplinary triage in an article titled 3 Welch and Davidson Patient presents for evaluation Name Entered Traditional Flow Map of Intake AMBULANCE presents for evaluation Back to Waiting Room Initial Assessment Back to Waiting Room Placed in Bed Primary Care Nurse Assessment Registration Calls Patient Physician Notified Patient Ready MD SEES Back to Waiting Room Patient Brought to Room Figure 1. Flow map of traditional triage Table 2. New Intake Models Traditional triage staffing Midlevel provider in triage Physician in triage Team triage No triage, “pull to full” Pivot nurse/abbreviated triage Triage to the diagnostic waiting room Intake kiosks Bio identification techniques Computerized self-triage “A Paradigm Shift in the Nature of Care Provision in the Emergency Department.”39 Since the first reports about placing a physician in triage were first published, many organizations have been experimenting with triage alternatives (eg, team triage). Several innovators have described success with having a team, often including a physician, nurse, and technician, that converges at the bedside to take the triage history together and formulate a diagnostic/therapeutic plan.40,41 A variation on this has been called the clinical intake area. In 2007, Gaston Memorial Hospital was seeing in excess of 80 000 visits annually and had a LWBS rate of 12%. They created a clinical intake area in their department for approximately $800 and streamlined the process to have a physician-led team examine, evaluate, and begin treating patients even when a room is unavailable. Their LWBS rates fell to 1.3%, and their Press Ganey scores (patient satisfaction) rose to the 99th percentile.42 No Triage Faculty physicians in the department of emergency medicine at the University of California, San Diego, 4 American Journal of Medical Quality XX(X) and sent to various patient streams. Using patient segmentation, like patients (those with similar LOSs and resource use) are fed into 1 of 3 patient streams based on the likelihood of admission, the ESI at triage, the resources anticipated, and the LOS. Triage to the Diagnostic Waiting Room Figure 2. Arrowhead Memorial intake cubicle have reported the most radical departure from traditional triage—no triage. If there is a bed in the department, the patient is brought back to a patient care space, and using bedside registration, care of the patient begins. This has led to reduced patient waits, decreased overall LOS, and reduced LWBS rates. This model has also been trialed in the ED Learning Community at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, with similar success. This process is sometimes referred to as the “pull until full” model for intake.43 As long as there is an empty bed, patients are brought straight into the department and intake is done at the bedside. Abbreviated Triage At Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, VA, Jody Crane, MD, tested a new abbreviated triage model. Mary Washington is a high-volume ED; their census topped 100 000 visits last year. A brief description of this truncated intake process follows: there are 5 elements included in this abbreviated triage, or initial assessment, to help segment patients to the appropriate patient care track. The 5 elements include the following: single phrase chief complaint allergies pain scale vital signs emergency severity index (ESI Level) At Mary Washington Hospital, it takes less than 6 minutes to triage a patient using this abbreviated scenario and, with 2 triage nurses around the clock, new patient intakes are performed at a rate of every 3 minutes.44 Dr Crane has added even more innovation to the processes at Mary Washington. Patients are assessed quickly by “pivot nurses” The “Triage to the Diagnostic Waiting Room” is another model that will seem very foreign to the health care worker. For patients who do not need to be supine on a stretcher during their ED stay, a physician in triage or team triage approach is used, and testing is begun in a multifunctional triage bay. The patient is then sent to a cubicle in a large waiting area with his or her family members. Ample efforts are made to occupy the patient’s time (among available resources are televisions, laptop portals, DVDs, snacks, games, and phones). This model has been used with success at Fairfax Inova Hospital in Fairfax, VA. At St Joseph Hospital of Orange, an intake team polices the waiting room and begins workups on selected patients.45 In a variation on this model, the patient and family members are asked to track the patient’s own progress on a large plasma screen tracker and to notify the staff when all test results are available. This involves the patient in the process while off-loading the task of monitoring for test results from health care providers. This frees the clinical staff for other tasks. Using patients and families to monitor results is called customer participation and is a key strategy in demand/capacity management used in other service industries. Intake Kiosks An even more futuristic vision for ED intake involves both process redesign and changing the physical plant. In the Annual ED ReDesign Course in Atlanta, GA, Jim Augustine, MD, describes an ED of the future where there are numerous rapid entry rooms. Patients pass through a kiosk and swipe a health identification card that downloads all pertinent health information into the computer system.46 A rapid assessment is done in these rooms. Then, using protocols that are carefully crafted using pattern recognition for chief complaint data, patients are assigned to the appropriate patient care stream. Assignment is done electronically and based on the chief complaint and vital signs. Registration occurs at the back end—after the medical screening exam. This futuristic model may not be so futuristic after all: Wellington Regional Medical Center in Florida has already implemented a “smart card” system that can be used in a kiosk to register patients. These magnetic stripe cards 5 Welch and Davidson link to the hospital information system and can locate all elements of the patient’s electronic health record. The information is password protected. Such an intake process removes traditional constraints to entering a patient into the emergency health care system, and it is exciting to imagine the operational improvements that will be possible in this area. Bio Identification Techniques Bio identification may be an adjunct to the efficient operation of the intake process. Innovative centers have begun trials using retinal scans, fingerprints, and palm scans to create a unique health care identification for the patient; these are extremely time-efficient methods. In particular, the palmar scanning method of bio identification deserves note.47 Steve Coluciello at Carolinas Medical Center has streamlined his intake process by using palmar scanning. At Carolinas Medical Center a palm print is used to generate an immediate identifier for a patient, which is then tied to an ID number. The ID number is later married to more demographic data. In less than 15 s, there is a way to identify the patient for testing and treatment. The device can ensure that the right patient is associated with the right medical record number. In addition to preventing identity fraud and mismatched records, the device can quickly identify unconscious or “altered mental status” patients who were previously scanned. One such palm scanning system is being marketed as the PASS system (Patient Access Secured System; Simply Scan LLC, Charlotte, NC). Carolinas redesigned their intake area, putting recliners, a multitude of supplies, an electrocardiogram machine, and point-of-care laboratory testing within reach of the physician and his team. Often the low-acuity ESI 4 and 5 patients receive a disposition right from this area. In fact, 45.5% of patients were discharged by the physician from triage. This is an effective way to off-load the main department when it is over capacity. These data are in line with the findings of other departments that put a physician out front: more than a third of patients seen by a physician in triage can be discharged quickly from there. Carolinas has seen improvement in door-to-provider time and the overall LOS during these trials.48 Computerized Self-Triage Perhaps the most cutting-edge application of technology to intake strategies has been reported by the University of Western Ontario. At London Health Sciences Center, triage occurs using pattern recognition programming of data that are entered by the patient into a computer in the waiting room. In the pilot feasibility study, the process was surprisingly fast (5 min, 32 s) and easy to use (92% would use again). In a substudy, the computer outperformed an emergency physician at obtaining data elements for patients with abdominal pain.49 This may be an effective strategy for some subsets of patients who present to the ED and will be part of our intake processes in the future. Discussion The impetus to change and improve on the intake process for the ED is growing and is multifaceted. From improved customer service/satisfaction and improved clinical outcomes to bureaucratic and regulatory requirements, the pressures to improve the quality of ED processes is growing. Every day EDs across the country struggle to meet the growing demands of the patients who show up at their doors, with capacity (in terms of space, staff, and resources) that is regularly outstripped by demand. How to match variable demand with fixed capacity?50 One part of an effective patient flow strategy is to keep patient flow through the health care system smooth and eliminate bottlenecks. One of the most commonly encountered bottlenecks to flow in the ED today is one of emergency medicine’s own making: triage. Data show that 65% of ED patients are seen between 10 AM and 10 PM. The night shift sees only 35% of the patient census.51 Patients are funneled into the department using a traditional triage model, which takes between 12 and 20 minutes to process patients into the department. These delays can be critical in terms of patient outcomes. The following sidebar tells a common story of how ED intake bottlenecks can detrimentally impact quality care. This is an actual case from an EDBA hospital and illustrates how patient safety is at stake when the intake process for patients is delayed. The pace is picking up as the evening wears on, and this ED, like most EDs, struggles to manage the daily surge that occurs. The triage nurse is taking the patients back one at a time and is not keeping up with new arrivals. The physician on duty is monitoring the tracking board and notes with impatience that an elderly man has been waiting 45 minutes for triage. The tracking system “chief complaint” notes that the man presented for evaluation of “foot pain/no trauma.” The physician calls to his charge nurse “Jill, can we bring that gentleman back? I am not busy and I can see him now.” The nurse appears flustered and under stress, “We’re going as fast as we can. It isn’t injured. We’ll get him in a minute.” Several more minutes go by, and now, the elderly man has been waiting for almost an hour to be seen. The physician studies him through the triage window, noting that he seems to be in pain and looks pale. The physician walks to the triage waiting area and introduces himself. He asks the patient 6 about his symptoms and learns that the patient had sudden onset of pain and at the same time noted his foot was getting cold. The physician kneels down and examines the foot, removing the sock and shoe. He is sick himself when he finds an ice cold foot that is turning black. There are no pulses in the foot. The patient has occluded the artery to his foot. Minutes count in terms of saving a limb. Time was wasted. As the ranks of the uninsured in this country grow and resources for funding health care for indigent and lowincome populations shrink, the ED is the health care safety net for many. No matter the insurance status or personal resources, the ED will see and treat all comers. It is the portal of entry into the health care system for many and the first step in the continuum of care. As increasing census has led to bottlenecks at intake, most EDs are too busy managing the care of the influx of patients to redesign the processes involved at intake. This is true in many areas of health care but particularly true for the ED in survival mode. How do you redesign a department where service never stops? This means that those EDs that have been able to innovate and discover new, improved, and alternative processes can help move the specialty forward in solving such problems. Those model EDs and their governing organizations need a venue to vet their findings and share their experiences. Yet innovations and ideas to improve operations are discovered by individual departments in a random and haphazard manner. To date, no journal focuses on ED operations, nor is there a textbook on ED processes to reference for ideas about to innovate in the ED. The ideas presented for dissemination in this article are the work of a collaborative learning model implemented by the EDBA. This demonstrates the value of such a model to advance ED operations. Limitations This is by no means an exhaustive review of the innovations being trialed around the country to improve intake models. It is the culmination of one organization’s collaborative learning project. Many of the new models and strategies are not yet published but are being disseminated at conferences and through learning communities like this one and those of The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the Voluntary Hospital Organization, Premier Healthcare, and others. This is an effort to introduce the broader specialty to the topic and stimulate new areas of innovation, dialogue, and research. This was a qualitative research project, presenting the new intake models being trialed as EDBA uncovered them. To date, there are not enough data to perform a strong comparative analysis of each model or a meta-analysis. That weakness is acknowledged, American Journal of Medical Quality XX(X) though such analyses may be possible in the future. The goal of this article is to provide a forum for dissemination of these new operational strategies. Conclusion Concerns about delays in care in the ED have been brought to the attention of the public by several highprofile news stories after patients have suffered dire consequences associated with long waits and delays in the ED. In one case, a 49-year-old woman presented to triage complaining of chest pain. She was triaged as semiurgent but was sent back to the waiting room. She was not seen immediately by a physician. According to records about the case, she waited in the waiting room for more than 2 hours. When a nurse went to bring her back for evaluation and care, she was not breathing, had no pulse, and was still sitting in the waiting room. She was not successfully resuscitated, and a subsequent homicide charge was filed against the Vista Medical Center ED.52 In another case of some notoriety, video surveillance cameras captured a Jamaican woman slumping to the floor in the waiting room of a psychiatric ED as apparently disinterested staff looked on. She had collapsed on the waiting room floor and was lying there for more than an hour before attempts were made at resuscitation.53 In a third high-profile case, a woman in an inner city “safety net hospital” lay screaming in pain and vomiting blood in the waiting room. She finally called EMS to transport her to another facility. She subsequently died of a perforated bowel and complications.54 Sadly, there are other stories. These cases point out in a dramatic way the problems and dangers of delays in the access to urgent and emergent care in our nation’s EDs.55 The public expects the health care system at large, and the specialty of emergency medicine in particular, to solve the access-to-care problems and intake issues. There is a case to be made for rapid intake in terms of the bottom line for the ED. The link between prolonged intake processes into the ED (as measured by long doorto-physician times) and patients LWBS by a provider was discussed at the beginning of this article and has a solid foundation in the literature. Patients who leave without being seen are in fact “customers” who have a higher than likely ability to pay for their health care, either with insurance or with assets. Would any industry allow paying customers to walk away? With many health care organizations struggling with narrower and narrower profit margins, it is important to see the timeliness of care in the ED and subsequent decrease in patients who walk away as a revenue capture opportunity. The case for ED efficiency and clinical outcomes has been made. At the beginning of this article, some references were cited from this body of literature (that is now Welch and Davidson growing at breakneck pace) that link timeliness of care to improved clinical outcomes for a wide array of illnesses, including acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, stroke, trauma, and sepsis. Because good outcomes are necessarily less expensive, timeliness and cost-effectiveness of emergency care can readily be linked as well. And it all begins with getting the patients into the ED in a timely and efficient manner. Besides the public scrutiny and attention to this area, innovation will be of great interest to many quality organizations and to bureaucracies like Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission. Although the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey does not look specifically at the ED experience or timeliness of care, how quickly patients’ pain is managed and how quickly patients are seen are 2 of the biggest correlates with patient satisfaction. The National Quality Forum recently endorsed 10 measures for quality in emergency care. Two of the 5 operational measures include (1) time to be seen by a provider and (2) left without being seen. Quality organizations and government agencies can be expected to drive this agenda for emergency medicine within the context of overall quality improvement in the ED. The time to innovate and re-create the intake process into EDs has come. The EDBA is a collaborative promoting innovation in ED care. A survey of its membership uncovered and collected many new ideas and innovations in lieu of the traditional triage model. These innovations were compiled and disseminated to the EDBA. The purpose of this review is to introduce the larger specialty of emergency medicine and its providers to these new models, technology, and physical plant changes that support innovation at intake. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. Funding The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.[AQ: 1] References 1. Owens P, Elixhauser A. Hospital Admissions That Began in the Emergency Department. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. HCUP Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Statistical Brief 1. 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2006 emergency department summary. National Health Statistics Reports. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr007.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2009. 7 3. Humphries K, Thompson C. VHA Performance measures and benchmarks. Paper presented at: VHA’s Conference on Optimizing Functional Capacity; November 2006; Tucson, AZ. 4. The Joint Commission. Sentinel event alert: delays in treatment. http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/ SentinelEventAlert/sea_26.htm. Accessed November 27, 2009. 5. Emergency Department Pulse Report 2008. Patient Perspectives on American Health Care. South Bend, IN: Press Ganey Associates; 2008. 6. Urgent Matters Patient Flow Newsletter. Engaging staff to reduce ED wait times to 30 minutes: recognition, rewards and review of data energizes Chicago’s Mount Sinai. Available at: http://urgentmatters.org/346834/318749/318750/318751. Accessed November 27, 2009. 7. Busy ED keeps promise of “door to doc” in 31 minutes. Hosp Case Manag. 2008;16:87-89. 8. Patel PB, Vinson DR. Team assignment system: expediting emergency department care efficiency. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:499-506. 9. Kyriacou DN, Ricketts V, Dyne PL, McCollough MD, Talan DA. A 5-year time study analysis of emergency department patient care efficiency. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34: 326-335. 10. Chan TC, Killeen JP, Kelly D, Guss DA. Impact of rapid entry and accelerated care at triage on reducing emergency department wait times, lengths of stay and rate of left without being seen. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:491-497. 11. Khot UN, Johnson ML, Ramsey C, et al. Emergency department physician activation of the catheterization laboratory and immediate transfer to an immediately available catheterization laboratory reduce door to balloon time in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007; 116:67-76. 12. Diericks DB, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al. Prolonged emergency department stays of non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction patients are associated with worse adherence to the American Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for management and increased adverse events. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:489-496. 13. Semplicine A, Benetton V, Macchini E, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in the emergency department for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:403-406. 14. Wardlaw JM, Zoppo G, Yamaguchi T, Berge E. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD000213. 15. Dean NC, Bateman KA, Donnelly SM, Silver MP, Snow GL, Hale D. Improved clinical outcomes with utilization of a community acquired pneumonia guideline. Chest. 2006;130:794-799. 16. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1-10. 8 17. Joint Commission Resources. 2009 Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals: The Official Handbook. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (The Joint Commission); 2008. 18. The National Quality Forum. NQF endorses measures to address care coordination and efficiency in hospital emergency departments [press release]. http://urgentmatters .org/media/file/NQF%20Press%20Release.pdf. Published October 29, 2008. Accessed November 27, 2009. 19. Michalke JA, Patel SG, Siler Fisher A, et al. Emergency department size determines the demographics of emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(3, suppl):39. 20. Siler Fisher A, Hoxhaj S, Patel SG, et al. Predicting patient volume per hour. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(3, suppl):6-7. 21. Welch S, Allen TA. Census, acuity and ED operations by time of day at a level one trauma and tertiary care center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:247-255. 22. Hoxhaj S, Jones LL, Fisher AS, Moseley MG, Rogers J, Reese CL IV. Nurse staffing levels affect the number of emergency department patients that leave without treatment. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:459. 23. Jensen K, Mayer T, Welch SJ, Harade C. Leadership for Smooth Patient Flow. Chicago: ACHE Management Series, Health Administration Press; 2006. 24. Jones SS, Allen TA, Flottemesch TJ, Welch SJ. An independent evaluation of four quantitative emergency department crowding scales. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1204-1211. 25. Jones S, Thomas A, Evans RS, Welch SJ, Haug PJ, Snow GL. Forecasting daily patient volumes in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:159-170. 26. Welch SJ, Augustine J, Camargo C, Reese C. Emergency department performance measures and benchmarking summit. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1074-1080 27. Wilson A, Shifaza F. An evaluation of the effectiveness and acceptability of nurse practitioners in an adult emergency department. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14:149-156. 28. Sakr M, Kendall R, Angus J, Sanders A, Nicholl J, Wardrope J. Emergency nurse practitioners; a three part study in clinical and cost effectiveness. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:158-163. 29. Levine SD, Colwell CB, Pons PT, Gravitz C, Haukoos JS, McVaney KE. How well do paramedics predict admission to the hospital? A prospective study. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:1-5. 30. Kosowsky JM, Schindel S, Liu T, Hamilton C, Pancioli AM. Can emergency department nurses predict patients’ dispositions? Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:10-14. 31. Sinuff T, Adhikari NK, Cook DJ, et al. Mortality predictions in the intensive care unit: comparing physicians with scoring systems. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:878-885. 32. Rocker G, Cook D, Sjokvist P, et al. Clinician predictions of intensive care unit mortality. Crit Care Med. 2004;32: 1149-1154. 33. Rodriguez RM, Wang NE, Pearl RG. Prediction of poor outcome of intensive care unit patients admitted from the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1801-1806. American Journal of Medical Quality XX(X) 34. Dent AW, Weiland TJ, Vallender L, et al. Can medical admission and length of stay be accurately predicted by emergency staff, patients or relatives? Aust Health Rev. 2007;31:633-641. 35. Terris J, Leman P, O’Connor N, Wood R. Making an IMPACT on emergency department flow: improving patient processing assisted by consultant at triage. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:537-541. 36. Travers JP, Lee FC. Avoiding prolonged waiting time during busy periods in the emergency department: is there a role for the senior emergency physician in triage? Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13:342-348. 37. Choi YF, Vong TW, Lau CC. Triage rapid assessment by doctor (TRIAD) improves waiting time and processing time of the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:262-265. 38. Borger R. Hospital and county case studies. Paper presented at: The California ED Diversion Project Meeting; May 27, 2008; Los Angeles, CA. 39. McD Taylor D, Bennett DM, Cameron PA. A paradigm shift in the nature of care provision in emergency departments. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:681-684. 40. Mayer T. Team triage and treatment (T3): quality improvement data from Fairfax Inova Hospital. Paper presented at: ED Benchmarks 2005 Conference; March 4, 2005; Orlando, FL. 41. Richardson JR, Braitberg G, Yeoh MJ. Multidisciplinary assessment at triage. Emerg Med Australas. 2004;16:41-46. 42. Besson K. Care initiation area yield dramatic results. ED Manag. 2009;21:28-30. 43. Protocols and Process Improvement Workgroup. IHI clinical and operational improvements for the emergency department, 2007–2008. Paper presented at: IHI ED Collaborative Meeting; June 17, 2008; Atlanta, GA. 44. Welch S. Quality matters. ED redesign: zones operate like mini ED’s. Emerg Med News. 2008;30:4. 45. Vega V, McGuire SJ. Speeding up the emergency department: the RADIT emergency program at St. Joseph Hospital of Orange. Hosp Top. 2007;85:17-24. 46. Augustine J. Designing for the future. Paper presented at: The First Annual Emergency Department Redesign Course; Atlanta’s Mart, December 10-12, 2008.[AQ: 2] 47. Savic T, Pavesic N. Personal recognition based on image of the palmar surface of the hand. Pattern Recognit. 2007;40: 3152-3163. 48. Coluciello S. Palmar scanning to facilitate ED intake. Paper presented at: Summit Exploring New Intake Models Into the Emergency Department; February 25, 2010; Salt Lake City, UT. [PE: THIS IS THE AUTHOR’S NOTE REGARDING REFERENCE 48: BY THE TIME THIS PUBLISHES, THE SUMMIT WILL HAVE TAKEN PLACE. I DIDN’T WANT TO TURN IT INTO UNPUBLISHED DATA ONLY TO HAVE TO CHANGE IT BACK.] 49. Benarola M, Elinson R, Zarnke K. Patient-directed intelligent and interactive computer medical history gathering Welch and Davidson systems; a utility and feasibility study in the emergency department. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76:283-288. 50. Davidson S, Koenig KL, Cone DC. Daily patient flow is not surge: “management is prediction.” Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1095-1096. 51. McGrayne J. Seventeen years of ED consulting: data from the Premier Consulting Database. Paper presented at: Taking Your ED From Good to Great: First Annual Advanced ED Operations Course; March 13-15, 2009; Las Vegas, NV. 52. Good Morning America. Illinois woman’s ER wait death ruled homicide. http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/Health/ story?id 2454685&page 1. Accessed January 11, 2010. 9 53. Good Morning America. On call. http://abcnews.go.com/ GMA/OnCall/story?id 2458644[AQ: 3] 54. Health News. LA County supervisors approve pact with university to restore hospital services to inner city. http://blog .taragana.com/health/2009/12/01/la-county-supervisorsapprove-pact-with-university-to-restore-hospital-servicesto-inner-city-16522/. Accessed January 11, 2010. 55. Wilson MJ, Nguyen K. Bursting at the Seams: Improving Patient Flow to Help America’s Emergency Departments. Washington DC: The George Washington University Medical Center, School of Public Health and Health Services, Department of Health Policy; 2004.