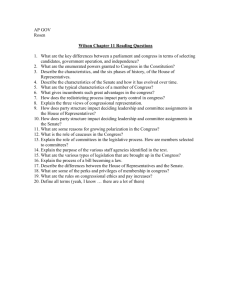

Congress - McGraw Hill Learning Solutions

advertisement