A Guide to Measures of Trade Openness

and Policy

H Lane David*

Indiana University South Bend

July 31, 2007

*e-mail: hdavid@iusb.edu

The author wishes to thank Thomas Willett, Arthur Denzau, James Lehman, and

participants at WEA sessions in 2003, 2004, and 2005 for support and invaluable

comments. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the author.

©2007 by H Lane David. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two

paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including ©

notice, is given to the source.

A Guide to Measures of Trade Openness and Policy

1

Introduction

To analysts and policymakers the issue of trade policy (or openness to trade) is

important. There is a large literature supporting the idea of a positive relationship

between trade openness and economic growth (Edwards [1992], Krueger [1997],

Wacziarg and Horn Welch [2003]). Trade openness is regarded by many, in both

academic and political spheres, as one being of the most important influences on

economic growth (along with the quality of institutions1 and tropical geography2). Given

that location is immutable and changing the quality of a nation's institutions is a longterm process, there has been a strong emphasis on trade openness (and trade

liberalization), particularly for developing countries.3

The findings on trade

liberalization, however, are contentious and the research and empirical findings not yet

conclusive (Rodriquez and Rodrik, 2001).

The focus of this paper, however, is not on the effects of trade policy

liberalization on economic growth but rather on how analysts measure trade openness

and policy. Beyond a general understanding that "openness" refers to trade barriers (and

how restrictive they may be) there is not a clear definition of the term. Empirical studies

have described openness in many ways and authors have used varied approaches in the

attempt to capture, via a summary measure, the multifaceted nature of trade policy. As a

result, a large number of measures of trade openness and policy have been created.

Notable examples include Leamer (1988), Dollar (1992), and Sachs and Warner (1995).

Harrison (1996) observed over a decade ago that, at that time, there was "... a dizzying

array of 'openness' measures, methodologies, and sample countries,...".4 The observation

holds true today, as there has been continued production of new measures of trade

openness and policy. As Greenaway et al (2002) noted:

"Even at the conceptual level, liberalisation is not unambiguous. In the

simple 2x2x2 trade model, one naturally thinks of it as tariff liberalisation.

In a more sophisticated setting with instruments affecting the domestic

prices of both importables and exportables, one can conceive of it as a

move towards relative price neutrality. Finally, one can think of second

best liberalisation, i.e. the substitution of more efficient for less efficient

instruments---typically tariffs for quotas. This ambiguity is reflected in

the range of measures used empirically."

Clearly, identifying an appropriate measure is a challenging exercise.5

1 Important contributions include Barro (1991), Knack and Keefer (1995), Easterly and Levine (2002), and

Rodrik, Subramanain, and Trebbi (2002).

2 See, for example, Hall and Jones (1999) and Sachs (2003).

3 It should be noted that there is an ongoing debate as to whether trade openness and trade policy are the

most important determinants of economic growth or whether the quality of institutions is more responsible

for economic growth. The debate is beyond the scope of this paper, but interested readers are referred to

Easterly and Levine (2002) and Sachs (2003).

4 p.420

5 Unless one decides to choose a measure based on the number of times it has been cited, which is a

mistake (as will be demonstrated).

2

Several authors (Harrison [1996], Edwards [1998], Rodriquez and Rodrik, [2001],

and Greenaway et [2002]) have tested the explanatory power of a number of these

measures to find which might be "best". Unfortunately, taken as a whole, the studies

provide little guidance for those wishing to use such measures. First, because the results

have been mixed, ranging from strong scepticism of the usefulness of such measures to

enthusiastic endorsement of them in general. Second, because it is difficult to compare

measures across the studies. Each study considers a relatively small (though generally

diverse) number of measures, ranging from three to nine, and there are few measures that

appear across studies. Finally, all the studies use different methodologies for testing the

measures, again making it difficult to compare results from one study to another even

where they contain common measures. It is safe to say that no single measure or group

of measures has emerged as a universally accepted indicator of trade openness and

policy, highlighting the need of analysts to carefully consider which will be the most

appropriate measure(s) for their work.

The purpose of this guide is to aid researchers faced with choosing among the

plethora of measures available. I have collected a large number of these measures into a

single dataset. Following Pritchett (1996) I also examine correlations between measures

to see if they appear to capture common trade policy elements. As the reader will see,

this does not resolve the discussion of what exactly constitutes "openness" and how best

to measure it. However, analysts who are familiar with the variety and construction of

these measures will be able to identify and use those best suited to their work.

Section 2 contains a brief review of the theory connecting trade and economic

growth, Section 3 reviews the literature on measures of trade openness, Section 4 puts

forth a taxonomy for the large number of measures now extant and then looks at the

strengths and weaknesses of each of the categories in the taxonomy, Section 5 examines

correlations between measures and across groups of measures for evidence that these

measures are capturing some common aspect(s) of trade policy, and Section 6 concludes.

2

Brief Theory of the Gains from Trade

Standard trade theory6 posits three channels through which trade liberalization

affects economic growth. First, there are gains from exchange. Consumers benefit

directly from lower prices of imports when trade barriers are reduced. Producers (and

ultimately consumers) benefit when they can import primary and intermediate inputs at

lower prices. Second, reducing trade barriers encourages firms to direct resources away

from previously protected sectors and towards those that have the greatest value added

(in both domestic and international markets). This results in gains from specialization as

sectors and industries which have comparative advantage in production expand their

output. Finally, there are gains from economies of scale. Lowering trade barriers has a

pro-competitive effect on firms. Previously marginal firms will be forced out of

6 This is the conventional (and dominant) theory of international trade, often referred to as the neoclassical

model of international trade. It has been challenged (primarily because of the assumption of perfect

competition) by models that incorporate imperfect competition, increasing returns, and learning effects.

Seminal contributions in this branch of the literature include Linder (1961), Posner (1961), Vernon (1966),

Krugman (1979), Caves (1985), Helpman and Krugman (1985), and Rodrik (1988).

3

business, allowing surviving firms to increase output and achieve lower average total

costs, allowing for greater efficiency in use of resources and, consequently, output.

These gains from trade can also be viewed inter-temporally. In the short-term

there are static, or efficiency, gains from trade liberalization. Trade restrictions create

price distortions that shift production between countries. Under domestic protection

against international competition, production is encouraged in sectors which are not

internationally competitive, and this forces consumers to pay higher prices. The removal

of these price distortions through the lowering of trade barriers leads to a more efficient

allocation of resources, as making domestic markets more open to competition from

foreign sources encourages production based on comparative advantage.

In the longer run there are numerous potential sources of dynamic gains. Reduced

trade barriers allow domestic industries greater access to intermediate goods, capital

goods, and technologies7 that foster economic growth. Industries that export can enjoy

the economies of scale that result from serving a larger market that includes both

domestic and foreign consumers. This leads to the specialization and economies of scale

mentioned previously, which in turn can lead to the growth of intra-industry trade.8

There will also be increased efficiency due to market competition reducing the degree of

monopoly power that existed prior to liberalization. For many developing countries this

is a significant step, as there are frequently state-run monopolies in important sectors of

these countries. Importantly, increased openness can lead to greater investment from

both domestic and foreign sources. Investment in the economy is crucial to economic

growth. For many developing countries with savings rates insufficient to develop the

capital markets which support economic growth, foreign direct investment (FDI) is

necessary for the economy to grow. Finally, increased openness imposes constraints on

government-induced distortions.9

Given that theory tells us greater openness to trade stimulates economic growth

and that casual observation suggests that countries which pursue more liberal trade

policies are more successful economically, the question that arises for researchers is

"How can we quantitatively capture a countries trade regime (or trade policy stance)?"

The next section begins to answer the question by reviewing the literature on the subject

of measures of trade openness and policy.

3

Some Background

There is a large (and still growing!) body of literature that documents a positive

correlation between trade openness and economic growth. Recent studies supporting a

7 Access to technological advances generated by developed countries can play a particularly important role

in the economic growth of developing countries. See, for example, Grossman and Helpman (1991) and

Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1995).

8 The majority of trade between industrialized countries is of an intra-industry, rather than an interindustry, nature.

9 See Grossman & Helpman (1991).

4

positive empirical relationship between openness and economic growth or growth in

income levels include those by Dollar (1992), Ben-David (1993), Sachs and Warner

(1995), and Edwards (1992, 1998). Up until the mid-1990s this finding was almost

unquestioned.10 However, the study of measures of outward openness published by

Pritchett (1996) brought to the field doubts that researchers were adequately capturing

openness. Pritchett examined the correlations between a number of measures of

openness to see if they were capturing some common aspect of trade policy or openness.

He found that

"Examination of the link between various empirical indicators used in the

literature to measure trade policy stance reveals that, with minor

exceptions, they are pairwise uncorrelated. This finding raises obvious

questions about their reliability in capturing some common aspect of trade

policy and the interpretation of the empirical evidence on economic

performance."

Thus, in an important way, the finding cast doubt on the interpretation of the

empirical evidence on openness and economic growth.

Since the publication of the Pritchett study there has been an active debate

concerning measures of trade openness. A study by Edwards (1998) used 9 measures to

test the relationship between openness and total factor productivity (TFP) growth as a

proxy for economic growth. His thesis was that, given the difficulties of creating

satisfactory summary indexes, it would be worthwhile to examine whether econometric

results were robust to the use of alternative measures. His finding, that TFP growth is

faster in more open economies, was robust to the choice of openness indicators,

providing support for the argument that a positive relationship between openness and

productivity growth exists.

However, the study by Edwards did not resolve the debate. Rodriguez and Rodrik

(2001), in a piece that reviewed extensively four measures (as well as three other studies),

argued that, owing to methodological problems with the empirical strategies used, the

relationship between trade policy (as reflected by openness) and economic growth had

not been well established. Their skepticism was driven by two concerns: first, the

measures used were either poor measures of trade policy or were highly correlated with

other factors affecting economic performance; and second, the mechanisms linking trade

policy and economic growth had not been well established. In their study they found

little evidence that lower trade barriers were associated with economic growth.

Greenaway et al (2002) postulated that both misspecification and the diversity

of the openness measures contribute to the inconclusiveness of the debate. They

addressed the misspecification issue by using a dynamic panel framework and found that

liberalization impacts economic growth with all of three measures of openness they

used.11

The problems of finding measures of trade openness that capture the relationship

between a liberal trade regime and economic growth are explored further in Winters et al.

(2004). They cite three sources of difficulty: 1) measuring trade stances is a difficult

exercise, 2) the direction of causation between openness and growth is difficult to

10 Leamer (1988) did find that the choice of measure was arbitrary.

11 It is important to note that the three measures used were very similar in nature, all of them being

dichotomous open/closed indicators. The weaknesses of dichotomous indicators are discussed further on.

5

establish, and 3) the interaction of trade policy with other policies has to be considered

when determining the effect on economic growth. With regards to the first issue, the

essential problem is that trade policy is multifaceted. Trade policy involves numerous

instruments, including (but not limited to) tariffs, non-tariff barriers (such as

administrative classification of goods, domestic content provisions, government

procurement provisions, restrictions on services trade, and trade-related investment

measures), and quantitative restrictions such as import quotas. There are problems with

the quality of data, assessment, and aggregation both within and across instruments.

The question of causality is an important issue. Trade policy itself may be a

function of other variables. For example, trade liberalization may be driven by income,

rather than the other way around. The push for greater trade liberalization through rounds

of trade negotiations since WWII has come largely from the industrialized countries,

which implies higher income may drive trade liberalization. However, on the other hand,

much trade liberalization has come about as a result of conditionality requirements

imposed by the International Monetary Fund when lending to countries undergoing crisis,

which implies a negative relationship in which liberalization drives income.

Macroeconomic policies as well as institutional and geographic variables can also

affect trade policies. It is thus likely that many of the measures of openness are

endogenously determined. Including an endogenous factor as an explanatory variable in

a regression model creates problems for understanding the relationships between the

explanatory variables (including trade openness) and economic growth. However, work

by Frankel and Romer (1999) and Frankel and Rose (2002) addressed this issue and

provided evidence of a positive causal relationship from trade (in the first) and openness

(in the second) to income, providing further support for a positive relationship from

openness to economic growth.

Finally, there is the observation that trade policy does not operate in a vacuum but

that its effects can be attenuated or ameliorated by other government policy actions.

Baldwin (2002) argues that to understand economic growth one must incorporate more

than just the effects of trade policies. He notes that restrictive trade policies are

"...usually associated with export subsidies to selected sectors, overvalued

exchange rates, large government deficits, extensive rent-seeking and

corruption, unstable governments, and so forth, but significant reductions

in trade barriers are also accompanied by important liberalization efforts in

these non-trade policy areas."

and he emphasizes the efforts of researchers who seek to combine various policy

measures into an index measure.

An approach that addresses the second of Rodriguez and Rodrik's criticisms (that

the mechanisms linking trade policy and economic growth have not been well

established) is to examine the channels by which openness could be linked to economic

growth. Wacziarg (2001) identified six channels through which trade policy can affect

growth: 1) macroeconomic policies, 2) the size of government, 3) price distortions, 4)

factor accumulation, 5) technology transmission, and 6) foreign direct investment. Using

a composite measure of trade openness the effect of trade policy on growth through

specific channels was estimated as the product of the effects of trade policy on the

channel and the effect of the channel on growth. The results support positive impacts of

openness on economic growth through these channels.

6

Despite the significant questions raised in recent years concerning both

methodology and the robustness of the conclusion of a positive correlation between

openness and economic growth, it is generally agreed that, at worst, the relationship

between openness and growth is bounded below by zero and that, more likely, it is the

case that increasing trade openness leads to increases in economic growth and income

levels. Researchers continue working to resolve the questions of whether trade

liberalization does stimulate economic growth in developing countries and on whether

measures of trade openness and policy can be successfully used, in particular for policymaking purposes. New measures of trade policy continue to be developed on a regular

basis and it is safe to say that economists and policy-makers are not about to give up

using such measures. Despite reservations, researchers continue to use existing measures

of trade policy and new measures continue to be developed.

4

Classification

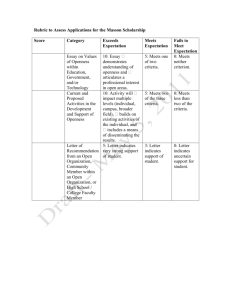

I have collected data for 30 distinct measures of trade openness and policy.

Because a number of the measures have been calculated for more than one period (in the

case of some cross-sectional measures), have an overall measure for the economy along

with sectoral sub-measures (for the manufacturing, natural resources, and agricultural

sectors), or have a measure and some variant(s) of it, there are a total of 70 measures in

the dataset.12 Given the large number of measures of trade openness and policy available,

it is useful to group and then compare them. In this section I do so by presenting a

taxonomy in which the measures are divided into logical groupings. I then review the

strengths and weaknesses of each category. This is a particularly important exercise in

light of the lack of a universally agreed upon definition of openness. The taxonomy used

is adapted from Rose (2002).13 Under this version measures of trade openness and policy

are divided into six groups:

1. Trade ratios

2. Adjusted trade flows

3. Price-based

4. Tariffs

12 The data set is available upon request from the author. The data set contains both cross sectional and

panel data collected from a large number of studies. The measures cover a variety of periods (depending

on the source) from 1950-2000 and 168 countries. A large portion of the data was obtained from the data

set for Rose (2002). Interested readers may wish to consult his website at

http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/arose/.

13 A simpler taxonomy that draws the distinction between causes and effects of trade policy is from

Baldwin (1989), who suggested that measures of trade barriers could be divided into two types: incidence

and outcome. Incidence-based measures attempt to gauge trade policies by observation of policy

instruments (both trade and non-trade) while outcome-based measures deal with the levels of trade flows

or attempt to assess the difference between the actual outcome and what would have transpired in the

absence of the trade barriers. It should be noted that this use of the term incidence is in contradiction to the

way economists generally employ the term i.e. the incidence of a tax describes who bears the burden of the

tax.

Another taxonomy is from Wacziarg (1998) who proposed that there are three broad categories of

measures of trade openness: outcome measures, policy indicators, and measures of effective protection

based on deviations from the predicted free trade volume of trade.

7

5. Non-tariff barriers

6. Composite Indices

It is important to note that the first three categories contain measures that are

based on trade flows or levels of prices while the rest seek to assess trade restrictions

directly. Put another way, the first three categories focus on outcomes while the last

three focus on policies. This is an important distinction. Ideally, one would want to

measure trade restrictions directly to determine the level of protection of a country.

However, in general, it is easier to measure flows and prices than barriers. Flows are

observable and quantifiable. Data on trade flows are gathered and disseminated on a

regular basis. For many countries trade data is available extending back several decades

(to the 1950s for developed countries and at least back to 1970 for a large number of the

developing countries). This data is often rich in detail, frequently available to three- and

four-digit SITC levels, and easy to compare across countries. Information on prices of

internationally traded goods is also generally available.

The availability of these types of data, however, is not a sufficient condition to

create good measures of trade openness and policy. The trade ratios category examines

measures that focus solely on trade flows and finds them wanting. While these types

measures are popular because of data availability and ease of calculation it will be shown

that they capture neither trade policy nor the effects of it. Of great concern is the fact that

there is no theory, only data availability, driving the measures. The other two categories

of flow- and price-based measures attempt to avoid this problem by using theoretically

founded models to create free-trade counterfactuals and then use the difference between

observed trade flows and theoretically predicted free-trade flows to estimate trade flows.

Conversely, data based on the observation of trade restrictions themselves (which

is the focus of the final three categories) is much harder to collect and work with. As will

be seen, even with tariffs, where analysts can go directly to the tariff schedule of any

country for data, quantification and interpretation are difficult exercises.14 Quantifying

and aggregating non-tariff restrictions suffers from the same problems to a greater

degree, as the researcher must calculate and combine the effects of what are frequently

fundamentally different types of instruments as well as problems arising from the use of

qualitative data. The result of these data issues has been the creation of far more flowbased measures than direct measures of barriers. The final category, composite indices,

seeks to combine tariff and non-tariff indicators with other economic and political

indicators. These measures are subjective in both the choice of indicators to be included

and in much of the data used.

Another important issue to be addressed is whether particular measures are based

on theory. Many of the measures (particularly in the trade ratios category, which is the

largest) have been created primarily because of data availability of and not because of a

theoretical basis. This lack of theoretical foundations has to be of great concern in both

the construction of measures and, even more so, in justifying the decision to use a

particular measure.

Wacziarg (1998) emphasizes these issues that the reader should keep in mind: 1)

outcome measures may not be well correlated with actual trade policies (because trade

outcomes are the result of a multidimensional process) but researchers tend to confuse the

14 The problems of working with tariff data are detailed in section 4.4.

8

two, 2) policy indicators such as tariffs, non-tariff barriers, etc., capture different aspects

of a country's trade policy, such that the use of a single one of these indicators may not be

very informative, and 3) one cannot be sure that deviation measures (the second two

categories of the taxonomy) create correctly estimated predicted free trade flows for the

counterfactuals.15 Wacziarg also argued against the use of outcome measures on the

grounds that they may be more reflective of levels of integration than capturing the

effects of institutions that affect openness.

4.1 Measures of Trade Openness and Policy

This section contains a discussion of the nature, strengths, and weaknesses of the

measures in the categories of the taxonomy. For each category at least one example is

reviewed.

4.1.1

Trade Ratios

This category contains the most widely used measure of trade openness and policy, the

simple and intuitively appealing trade ratio measure of openness, most often calculated as

(Exports + Imports) / GDP. Commonly referred to as openness (which is, I think, a

misnomer) it is also known as trade share or trade intensity.16 The measure is popular

because data are readily available for many countries and, as it is quite commonly used, it

allows for comparability across studies.

A variant of the trade ratio measures are import penetration ratios (Leamer, 1988).

Not widely used, these ratios are calculated by dividing imports of a given commodity by

the total domestic supply of that commodity. Total domestic supply is defined as imports

plus gross output of the domestic producers minus exports of that commodity. These

ratios seek to provide a broad indication of the international competitiveness of domestic

producers. These measures have been calculated as overall aggregates for the entire

economy, as well as sectoral measures for the manufacturing, agricultural, and resource

sectors.

Despite the overwhelming popularity of the simple trade ratio measure,

researchers should be aware that this measure is a measure of country size and integration

into international markets rather than trade policy orientation. A few examples using

year 2000 data for the well-cited openness measure (in current prices) from the Penn

World Tables (PWT6.1) serve to illustrate the point. First, the five least open countries

are (in order) Japan, Argentina, Brazil, the United States, and India. While it is clear that

these countries have trade restrictions in varying degrees, it is difficult to believe that

they are the most restrictive countries in the world in terms of trade policies. It is most

likely that the large size of the economies relative to their volumes of trade is responsible

15 Reasons why counterfactuals may not be estimated properly include possible omitted variables in the

estimation of free trade flows, the possible correlation of some of the determinants used to estimate the free

trade flows with trade policies, and an increased downward bias associated with measurement error in the

observed volume of trade.

16 Calculated using either current prices or base year prices.

9

for these results rather than trade policies (China ranks 24th out of the 136 countries for

which the data is available).

Second, many of the comparisons across countries are not plausible with respect

to the degree of difference of openness between them and, for example, the U.S. One

should not be surprised to learn that Singapore and Hong Kong are, by this measure,

ranked as the most open countries. However, according to the data they are 11.2 and 9.7

times more open than the United States. What is surprising are comparisons involving

less developed countries still struggling with economic (and social and political)

development. Jamaica is almost 4 times more open than the U.S. and African nations

such as Ghana and Congo 4.5 and 5.1 times more open. Even many of the former

communist countries are listed as far more open than the U.S., for example, the Ukraine

and the Czech Republic at 4.5 and 5.6 times respectively.17 Given these examples, it is

hard to see that this measure produces satisfactory ordinal rankings much less the

cardinal ranking implied by the precision of the measures. What is obvious from

examining the data is that these measures show that small countries are relatively more

engaged in international trade than large countries, returning us to the contention that this

is a measure of size and not policy.18 This is reflective of smaller countries being

constrained by the size of their domestic markets and needing to trade to achieve

specialization and economies of scale much more than it is a measure of trade policy or

openness.

At best the trade ratio measure would be a highly imperfect proxy for trade

policy. It is difficult to substantiate the claim that trade ratios changes only in response to

trade policy changes. Trade is affected by many factors in addition to trade policy:

structural and environmental factors such as differences in geographical variables,

resource endowments, the size of the country, the level of economic development, the

state of the global economy, etc. Consider the impact of a sudden increase in oil prices.

The price increase would show up in the numerator of the measure, causing the country

to appear to have increased its openness when in fact no trade policy changes had

occurred. If the price increase was severe enough and of sufficient duration it could lead

to an economic recession, which would reduce the denominator in the measure, again

making the country appear to have become more open when that was not the case.

Most damning, there is no theory supporting the idea that trade ratios reflect trade

policies. In fact, trade ratios have been used to support theory tying openness to country

size rather than growth. Alesina, Spolaore, and Wacziarg (2000) develop a model of the

relationship between openness and the equilibrium number and size of nations. They

argue that trade liberalization and size are inversely related and use trade ratios in the

empirical test of their model. Their reasons for doing so are: 1) that they feel it is a

"broad" measure, capturing a policy component, a gravity component, and other

determinants of trade openness such as differences in political and legal systems,

languages, etc.; 2) the data is readily available; and 3) use of the measure allows for

comparability across studies.

17 The actual data for the countries cited are Japan 20.095, Argentina 22.215, Brazil 23.028, United States

26.197, India 30.449, Jamaica 99.332, Ukraine118.236, Ghana 118.75, Congo 132.505, Czech Republic

146.617, Hong Kong 295.186, and Singapore 341.591.

18 For a good exposition and a model of this idea see Alesina and Spolaore (2003), Ch. 6, pp.81-94.

10

Alesina et al reach two conclusions. First, that country size correlates less with

growth for countries that are more open to trade, and second, that the link between

openness and growth is stronger for small countries than large ones. Given the flawed

nature of the measure, I think they read too much into their findings.

I hope that I persuade my readers that none of Alesina et al’s points are good

reasons to use such a measure to capture trade openness or trade policy. By their own

admission it is too "broad" to be a measure of trade policy and is driven by data not

theory (they use the measure to "prove" their theory, not the other way around). As for

the last reason, comparability is not an issue if the measure does not capture what it is

supposed to.

A number of attempts to improve trade share measures have been undertaken.

However, empirical work to improve trade ratios has yet to prove that they serve as

measures of trade openness and policy. Pritchett (1996) noted that highly protectionist

policies should reduce the amount of economic activity that is traded. To estimate the

size of this reduction he used "structure adjusted trade intensity" measures, which are the

residuals from a regression of trade intensity on structural characteristics such as

population, land area, level of per capita GDP, and transport costs.19 The residual from

the equation implies by how much a country's openness differs from what would be

expected of a country with the same characteristics. This is not a large improvement,

however. As Pritchett himself notes "...the regression adjustment is ad hoc and

atheoretic."20 Changes in structural characteristics or omitted variables (such as foreign

demand) may cause changes in the residuals that would be interpreted as changes in trade

policy when policy has not changed. Nor does the measure establish a common

benchmark, such as a free trade or an average level of the residuals that would facilitate

comparisons across countries.

Frankel and Romer (1999) attempt to improve on the standard trade ratios

measure by creating one constructed using a number of geographic characteristics. Their

finding that a 1 percent increase in the trade to GDP per person ratio raises income per

capita by at least one-half percent has been widely seized upon. Yet they themselves

admit the measure is "clearly an imperfect measure of economic interactions with other

countries,...”. They show that the hypotheses that the impacts from trade and size are

only marginally rejected at standard levels of significance. Finally, they caution that their

results "...cannot be applied without qualification to the effects of trade policies." This is

far from convincing evidence.

More recently some authors such as Alcalá and Ciccone (2004) have argued that

it is theoretically preferable to use a measure of "real" openness rather than nominal trade

share measures. Real openness is defined in their work as imports plus exports in

19 A potential problem exists with any regression-based index that uses the residual from a regression to

proxy for an excluded variable: these indices accurately capture variations in the excluded variable only if

the model is correctly and fully specified. If any variables that should be included are excluded from the

estimated equation, the effects of all of them will be included in the index. This caveat, that the measures

themselves are sensitive to the specification of the underlying models that produce them, applies to many of

the measures that follow as well and should be borne in mind when deciding among measures.

Wacziarg (2001) maintains that simple trade ratio measures should be viewed as resulting from a

mixture of policy, factor endowments, and gravity determinant variables.

20 p. 313

11

exchange rate US$ divided by GDP in PPP US$.21 This is a constant price equivalent of

the simple trade ratio measures and is the total trade as a percentage of GDP measured in

constant prices.22 In their paper, which examines the relationship between trade and

productivity, they show that countries that are more productive due to trade may not

necessarily have higher trade ratios using nominal measures. This can occur because of

greater productivity gains in the tradable manufacturing sector than in the non-tradable

services sector, which leads to a rise in the relative price of services, which in turn leads

to a decrease in the nominal measure of openness. They contend that using a real

measure of openness rather than a nominal one eliminates distortions due to crosscountry differences in non-tradable goods relative prices.23 An extension of this

approach is to calculate the real growth rates of the GDP of each of the export partner

countries and compare these with the real growth rates of exports to those countries. If

exports to these partners are growing faster than the real GDPs of the partner countries,

then the export ratios (as opposed to overall trade ratios) would be growing. However,

while agreeing with their contention that a real measure is superior to a nominal one, it

does not change the fact that trade share is still a measure of size rather than trade policy.

Caution should also be exercised when considering the use of import penetration

ratios. While import penetration ratios have long been found to be positively correlated

with levels of import protection, in the late 1970s trade theorists realized that trade

protection should be considered as an endogenous policy (e.g., Brock and Magee 1978).

This interpretation of implies that the impact of trade liberalization tends to be

underestimated by the import penetration variable. The logic is that as import flows rise

domestic import-competing interests are likely to mobilize and lobby for higher

protection (Trefler 1993).24

However, one can also argue the opposite, that there could be a negative

correlation between import penetration and import protection. In an open economy,

while there may be resistance to liberalization from selected sectors, there is probably a

limit on how much the affected industries can influence trade policies. Most likely the

affected sectors can temporarily increase protection but it is very unlikely that they will

be able to get permanent (possibly prohibitive) import tariffs. Thus it may be the case

that we would find a negative correlation in more open economies and a positive

correlation in more protectionist economies.

Two final weaknesses of trade ratios measures (and these are criticisms of all

outcome-based measures in general) need to be addressed. First, there are timing lags

between when policy changes are decided upon and when a measure reflects that policy

change. It takes time to implement policy and it takes further time for producers,

importers, and consumers to react to the change. The length of the period is likely

21 They use log real openness instead of real openness because their theoretical framework does not

determine the functional form of the relationship between real openness and productivity.

22 For examples of other ways real openness has been calculated see Dollar and Kraay (2002) and Bolaky

and Freund (2004).

23 The main finding of their study is that trade has a positive effect on productivity. For a dissenting view

see Rodriguez and Rodrik (2001). A related issue is whether there is reverse causation from productivity to

trade. On this see Ades and Glaeser (1999), Frankel and Romer (1999), and Alesina, Spolaore, and

Wacziarg (2000).

24 Goldberg and Maggi (1999) estimate import penetration interactively with a dummy variable of political

organization but find mixed results.

12

variable, different across countries, dependant on other factors such as long term

contracts and thus it is difficult to separate out the effects of trade policy changes from

other structural or environmental factors that change during the period using these

measures.

Second, business cycles cause movements in these measures unrelated to changes

in trade policy. The measures will be contaminated by these movements, implying that

reform is more effective than it actually is should reform coincide with an upswing of the

business cycle or making reform look less effective should it occur during a downturn of

the business cycle.

I do not recommend the use of trade share measures as indicators of trade

openness and policy. As mentioned earlier, they serve well as measures of country size

or country integration into the global economy, but their interpretation should not be

taken beyond that. Researchers need to bear in mind that their wide usage is not proof of

their ability to capture a country's trade openness or trade policies.

The use of a data-driven, atheoretic measure is difficult to justify in the presence

of a large body of trade theory. Thus, to repeat, there is no basis for the argument that

this measure is capturing changes in trade policy and there is little, if any, justification for

using it. Even the claim of comparability across studies fails when the measure does not

capture either trade barriers or the effects of them.

4.2

Adjusted Trade Flows Measures

The Adjusted Trade Flows category uses deviations of actual trade flows from

predicted free-trade flows (the counterfactual) to form measures of trade policy. The

counterfactuals are assumed to represent what would have happened under different

policy choices, e.g. free trade policies. It is important to note that all such outcome

measures are sensitive to the model chosen to construct the counterfactual.25 Choosing

among the measures in this category thus requires consideration of the underlying

models. Users must think carefully about what explanatory variables they consider

important and the form of the relationship between those variables. Fortunately, the

models used to produce adjusted trade flow measures have theoretical foundations unlike

many measures whose creation is simply driven by data availability) to which users can

turn for guidance.

This section considers two methodologies.26 The first uses an empirical factor

proportions model (also known as the Hecksher-Ohlin factor model) in which trade flows

are determined primarily by resource endowments.27 Factors frequently included are

capital, labor, land, oil production, coal, minerals, GDP-weighted distance, and the trade

balance in terms of net exports. Leamer (1988) used a regression based methodology

25 Pritchett (1996), p. 312.

26 For the factor proportions models a useful overview is contained Appleyard & Field (2001, pp.118-139),

while for the gravity model important works include Anderson (1979), Deardorff (1998), and Anderson and

van Wincoop (2003).

27 The major conclusion of the Hecksher-Ohlin analysis, known as the Hecksher-Ohlin Theorem, is that

countries will export those products which use relatively intensively their relatively abundant factors of

production and will import products that use relatively intensively the relatively scarce factors of

production.

13

employing a factor model to estimate disaggregated net trade flows for 183 commodities

at the three digit SITC level, using 1982 data for 53 countries.28 He then used the

differences between the predicted trade flows and actual measured trade flows as adjusted

trade intensity ratios, using the difference for a country weighted by that country's GDP.29

Leamer (1988) also estimated measures which he termed "measures of trade

intervention". Based on the observation that trade policies do not always have a negative

impact on trade, but that some trade policies are designed to increase the flow of trade

from a country (export subsidies for example), his estimations of the rate of intervention

were an attempt to measure the degree to which trade was distorted by policy.

The second methodology involves use of the gravity model. Gravity models from

Newtonian physics have been widely used in a variety of applications. They have been

used to in the social sciences to explain a wide range of flows including labor migration,

commuting, customers, hospital patients, and international trade, and have also been used

to estimate the impact of policies in these areas. Gravity models of international trade

and integration have been used extensively and are widely accepted (so much so that

Eichengreen and Irwin (1998) have called the model the "workhorse for empirical studies

of [regional integration] to the virtual exclusion of other approaches."30). They are

popular because of their theoretical foundations and their strong fit to empirical data.

An important difference between empirical factor proportions models and the

gravity models is that the former focus on net trade flows while the latter focus on

bilateral trade flows. The use of gravity models is advantageous as bilateral trade flows

may more accurately capture the effects of trade policy changes, such as becoming a

member of a free trade area. Examination of bilateral flows also allows for estimation of

trade creation and trade diversion effects. Net flows, on the other hand, capture

aggregate changes and it is more difficult to distinguish the effects of trade policy

changes from broad movements in the international economy using aggregates.

In the basic form of the gravity model of international trade, trade flows between

two countries are assumed to be positively related to size (as measured by national

incomes) and negatively related in the distance between the two countries (which proxies

for the cost of transport between them). The basic gravity model is expressed in loglinear form as:

ln M ij = α + β ln Yi + γ ln Y j − δ ln Dij + ε ijt

(1)

where Mij is the total trade flow from country j to country i, Y’s are national incomes, and

D is a measure of the distance between the countries.

Extended versions of the gravity model have included population or per capita

income as additional measures, creating what is known as the augmented gravity model.

The use of one of these variables allows for non-homothetic preferences in the importing

28 As the reader has no doubt begun to note, many of these measures require large amounts of data for

estimation. I will not continue to point this out but recommend readers to bear this in mind (particularly if

they are considering constructing a new measure).

29 This measure is calculated (for country i) as TIRi = (

A

∑N

ij

− N ij* ) / GDPi , where N ij is the value

j

*

ij

of net exports and N is corresponding number predicted by the model.

30 P. 33.

14

country as well as serving as a proxy for the capital-labor ratio of the exporting country.31

Further explanatory variables, such as contiguity or a common language between a

country pair, have also been used.

An appealing advantage of gravity models is that they provide an approach to

deal with the problem of the endogeneity of trade. Frankel and Romer (1999) show this

by focusing on the component of trade that can be attributed to geographic factors, such

as distance. Distance between trading partners is not something that is determined

arbitrarily or that changes over time.32 Using instrumental variables based on

geographical characteristics (characteristics that are not affected by income or

government policy and are thus exogenous to the model) they find that trade has a

positive effect on income. This suggests that trade policy liberalization has a positive

effect on income, though they do caution that a:

".... limitation of the results is that they cannot be applied without

qualification to the effects of trade policies. There are many ways that

trade affects income, and variations in trade that are due to geography and

variations that are due to policy may not involve exactly the same mix of

the various mechanisms."33

A recent modification of the gravity model is found in Hiscox and Kastner (2002).

They use trade as a proportion of income for their dependent variable in the basic

equation:

ln( M ij / Yit ) = α it + β ln Y jt − δ ln Dij + ε ijt

(2)

They also use an augmented model, with relative factor endowment differentials

as additional variables to capture factor-proportions type effects. The augmented

equation is:

ln( M ij / Yit ) = α it + β ln Y jt − δ ln Dij + λ ln Lijt + κ ln Wijt + ε ijt

(3)

where Lij and Kij are measures of the differences in endowments of land and capital and

Wjt is the wealth of the exporting country.34 From these equations they find importingcountry-specific and time-specific effects, which they compare to the sample mean in

each year to evaluate the distorting effects of each country's policies. The reported

figures are the deviations of the estimates from a "free trade" benchmark to capture

implicit protection effects of other policies that act as barriers to trade (including

domestic policies concerning industrial policy, labor market policies, etc.).

As with all measures, the ones in the adjusted trade flows category have

disadvantages. The largest concern is that there is no way of assuring that the

counterfactual accurately produces the volume of trade that would occur under free trade.

As Hiscox and Kastner themselves note:

31 Bergstrand (1989).

32 It can be argued that the effects of distance have been reduced through improvements in transportation

and reductions in the cost of transportation. Baier and Bergstrand (2001) find that transport cost declines

account for approximately 8% of the growth in trade between OECD countries for the period encompassing

the late 1950s to the late 1980s. Whether this conclusion can be extended to include developing countries

is open to debate. Hummels (1999) finds that, for the post-WWII period ocean freight rates have increased

while air freight rates have decreased dramatically.

33 P.395.

34 See pp.9-14 of Hiscox and Kastner (2002) for further details.

15

"A key problem here is that we cannot distinguish between the effects of

changes in trade policies and other changes, specific to particular

importing countries in particular years, that also affect trade flows and are

not accounted for in the model."

Our confidence in the counterfactual depends crucially on both the model being correctly

specified and that there are no errors in the data, conditions that are unlikely to be

completely satisfied. A particular concern is that some determinants of trade will be

omitted from the model. However, given the strong theoretical underpinnings of these

models, combined with their robust empirically proven success in other applications, I

urge analysts to consider the use of measures from this category. There is much to be

said for using a measure having theoretical foundations, unlike many found in the other

categories. If the investigator is confident that the model producing the measure has been

well-specified, then justification for the choice of one of the measures in this category is

much clearer.

I believe that the use of gravity model-based measures may be the appropriate

choice for many applications that involve trade policy or trade openness as an

explanatory variable. This broad recommendation comes with a few caveats, mostly

concerning data. While not as data-intensive as the factor endowment approach these

measures still require relatively large amounts of data, as they focus on bilateral trade

flows rather than aggregate flows (across all trading partners). In addition, it is important

maintain in consideration is that these measures are highly sensitive to the data used. It is

often the case that simply changing the time period of, or the countries in, the sample can

have a large impact on the results of the estimation. Users of these types of measures will

need to examine the underlying data carefully. Data availability (as always) is

problematic. Data for industrialized countries may be available back to the 1950s while

that for developing countries may not begin until 1970 or later, potentially leading to a

small sample size. One would generally like to use the longest time period possible but

results are more easily compared when the data time periods are the same for the

countries in the sample. In some cases it will make sense to separate developing

countries from industrialized ones, to make for comparable series.

4.1.3

Price-Based Measures

Price-Based measures attempt to capture trade policy by seeking price distortions

in either goods markets (by comparison with international prices) or with currencies

(generally through the black market premium). Advocates of price-based measures claim

that they capture the effects of both tariff and non-tariff barriers and that economic

interpretation is easier than with the flow based measures, as countries with high price

levels over time would be seen as countries with a relatively high levels of protection.

A widely-cited example of a measure using goods price distortions comes from

Dollar (1992), who constructed two indices, an "index of real exchange rate distortion"

and an "index of real exchange rate variability". For the first, Dollar took data on the

estimated real prices for a common basket of goods and removed the effect of systematic

16

differences arising from the presence of non-tradables.35 The index is supposed to

measure the extent to which the real exchange rate is distorted away from its free trade

level by trade policies. The index of real exchange rate variability is calculated by taking

the coefficient of variation of the annual observations of the index of real exchange rate

distortion for each country over the same period.

Simply looking at levels of prices of tradable goods across countries may be

misleading, however. Trade policies work by altering relative prices within an economy

but the effects of trade policies on the level of prices in one country relative to another

are not clear-cut. Rodriguez and Rodrik (2001) point out that for the index of real

exchange rate distortion to be theoretically appropriate three conditions must hold: 1)

countries are not using export taxes or subsidies,36 2) the law of one price holds,37 and 3)

transport costs and geographic factors do not create systematic differences in price levels

between countries.

It is quite unlikely that all three of these conditions hold at the same time. Indeed,

it is likely that none of them hold in many cases. Countries can and do use multiple trade

restrictions simultaneously on both imports and exports.

This holds true for

industrialized nations as well as developing countries. It is also, at best, dubious that the

law of one price holds continuously. Substantial evidence indicates that deviations from

the law of one price are frequent and that these deviations die out only in the very long

run (Rogoff 1996).38 Finally, it has been shown that geographic factors (and thus

transport costs) are important in explaining trade (see, for example, Frankel and Romer

[1999]). The index of real exchange rate variability measure undoubtedly reflects the

effects of geographic factors in addition to exchange rate and trade policies but has no

mechanism to differentiate between them. As well, and this is a criticism of price-based

measures in general, price-based measures are unable to differentiate between the effects

of domestic market distortions induced by macroeconomic policies and those induced by

trade policy interventions.

35 To do this, he regresses the real price level (RPLi) of the basket of goods on the level and

square of GDP per capita and on regional dummies for Latin America and Africa, as well as year

dummies, which gives him a predicted value, ( RPL i ) . The index of real exchange rate distortion

is then:

RPLi

RPL i

averaged over the ten-year period 1976-1985.

36 This condition is required because tariffs and NTBs, which fall on imports, are not the only tools of

trade policy. Other important tools include export subsidies and export taxes that, if they play more than a

minor role in the trade policy of a country, will affect the ranking of trade regimes. The effect of these

instruments combined with those of import barriers must be considered when using price-based measures.

Countries that try to offset the resource allocation distortion induced by import restrictions through the use

of export subsidies will appear to have higher levels of protection than countries that do not do so. More

perversely, economies that have both import restrictions and export taxes will be seen as less protectionist

than those that rely on import restrictions alone.

37 A consequence of the law of one price failing to hold is that nominal exchange-rate movements affect

the domestic price level of traded goods relative to foreign prices. Therefore a nominal appreciation will

make a country appear to have a higher level of protection while a depreciation make it seem to be more

open.

38 Rogoff concludes that the speed of convergence to purchasing-power parity (PPP) is extremely slow,

perhaps 15 percent per year.

17

Rodriguez and Rodrik demonstrate that Dollar's index of real exchange rate

distortion is neither a robust correlate of growth nor robust to alterations in the

specification of the estimating equation. They dismiss the second measure, the index of

real exchange rate variability, as "...a measure of instability more than anything else." In

addition to their critique, one must add the usual list of suspects that bedevil many of the

measures reviewed in this paper: these measures require large amounts of information on

domestic prices and border prices, as well as adjustments for transportation costs,

markups and quality differences, and the data are not always readily available, especially

for developing countries. Thus, overall, models based on finding distortions in goods

prices across countries have sufficient problems that one should feel uneasy using them.

The most popular currency price measure is the black market premium, which is

measured as the deviation of the black market exchange rate from the official exchange

rate. The black market premium is not a direct measure of trade openness but rather

measures the extent of rationing in the market for foreign currency. The argument for

using the black market premium as a measure of trade openness is that foreign exchange

restrictions act as a barrier to trade. Edwards (1992, 1998) used the black market

premium as a proxy for trade restrictions on the assumption that countries with more

restrictions on imports and fixed exchange rates would often have overvalued currencies;

thus it serves as a broad measure of the extent of distortions in the external sector (i.e. not

only distortions in trade but in capital flows and other markets as well).

Rodriguez and Rodrik have argued against the use of this measure as well.

They contend that it is not a good measure of trade policy stance, as it most likely reflects

a wide range of policy failures (poor macroeconomic policy, weak government, lack of

rule of law, and corruption) as well macroeconomic and political crises. The black

market premium is thus serving as a proxy for many variables which are unrelated to

trade policy. Crises and policy failures, rather than the trade-restricting effects of the

black market premium, would be the reasons for low growth in this case.

The appeal of price-based measures derives from their theoretical foundations.

Unfortunately, the constraints of both data and methodology at this time lead me to

believe that, for the present, price-based measures are inadequate for capturing trade

restrictions. It is most likely that price-based measures in general are affected by much

more than just trade policies. I do not recommend their use.

4.4

Tariffs Measures

Tariffs are highly visible restrictions of trade and can be viewed as the most direct

indicators of restrictions. They are popular because data is available.39 There are a

number of measures of tariffs that have been widely used by trade economists: simple

tariff averages, trade-weighted tariff averages, revenue from duties as a percentage of

39 Nominal tariff rates are either ad valorem, based on the value of the good, or specific, per unit of the

good. Specific tariffs can be converted to ad valorem tariffs by dividing the specific tariff amount per unit

of a good by the price of the good.

18

total trade (which is a shortcut method for estimating the import weighted average tariff),

and the effective rate of protection (ERP).40

Gathering data on tariffs, however, can be challenging. Countries do not report

their weighted average tariff rate or even their simple average tariff rate every year, so the

most recent data may be several years old. The quantity of data required for calculating

weighted tariffs and ERPs is daunting. The data for both tariff and non-tariff indicators

(discussed in the next section) are measured with some error due to weaknesses in the

underlying data (issues of both collection and coding) and there are frequently problems

with missing data due to activities outside the formal market such as smuggling.

Problems thus arise when attempting to aggregate data into these types of index measures

and this can make consistent cross-country comparisons a difficult task.

An example that illustrates the problems of constructing such a measure is the

trade policy component of the Index of Economic Freedom.41 This component is based

on a country's weighted average tariff rate (weighted by the imports from the country's

trading partners). As noted, many countries do not report their weighted average tariff

rate every year and for some of the countries in the 2005 Index the last reported weighted

average tariff data was as old as 1993. In these cases the authors of the Index were

forced to turn to less direct measures of tariff barriers. If the weighted average tariff rate

was not available, the authors then used the country's average applied tariff rate; if the

country's average applied tariff rate was not available, they used the weighted average or

the simple average of most favored nation (MFN) tariff rates. In the case where neither

the applied tariff rate nor MFN tariff data were available, the authors based their grading

on the revenue raised from tariffs and duties as a percentage of total imports of goods. If

data on duties and customs revenues are not available, they either used data on

international trade taxes or they analyzed the overall tariff structure of the country and

estimated an effective tariff rate.42 Obviously, the progression through the different

methodologies implies an increasing chance of error and, as the methodologies move

further from estimating weighted average tariff rates, a decreasing ability to make useful

comparisons across countries.43

Despite the fact that these measures are the most direct indicators of trade policy,

they are viewed as poor indicators of trade policy. First, as mentioned, tariff protection

affects producers and consumers differently. Second, import elasticities are likely to vary

across products and countries, thus implying that a tariff of a given magnitude may have

40 Also known as the effective tariff rate. The ERP for any industry j is commonly calculated as

ERPj =

t j − ∑ i aij ti

1 − ∑ i aij

, where aij is the free trade value of input i as a percentage of the free trade value of

the final good j and tj and ti are the tariff rates on the final good and any input i.

41 Published annually by The Heritage Foundation and Dow Jones & Company, Inc. See pp.57-77 of the

2005 edition for an explanation of the components of the Index.

42 Pp.60-61.

43 The authors of the Index recognize that tariff barriers are not the only impediment to trade and thus,

because the trade policy component also considers non-tariff barriers and corruption as well, the measure is

included in the informal or qualitative category rather than the tariff barriers category. It does, however,

serve to illustrate well the difficulties of constructing measures of tariff barriers. It is also a good example

of a measure that is used by policy makers, as it is one of the criteria considered by the Millennium

Challenge Corporation in selecting the developing countries that are eligible for Millenium Challenge

Account assistance (Millenium Challenge Corporation, 2005).

19

different effects both for differentiated products44 in a single country and for the same

product across different countries. Third, collecting comprehensive tariff data on all

product categories is a large undertaking not often carried out. Even when such data is

compiled, the researcher is still faced with the question of the appropriate weighting

scheme. Finally, the typical trade regime in developing countries also restricts imports

with other barriers as well, such as those discussed in section 4.5.

The list of problems with tariff measures goes on. It is well known that

unweighted average tariff rates tend to overstate the height of average tariffs because they

include very high and prohibitive tariffs whereas weighted average tariff rates tend to be

biased downwards because the import levels of high-tariff items tend to be low. There is

concern about the use of nominal tariff rates reported in tariff schedules. While nominal

tariff rates reflect the impact of trade barriers on consumers, they generally do not reflect

the effective protection granted to producers because of differing tariffs on imported

inputs and final products. Researchers must be clear that they are using the appropriate

measure given that the welfare effects of tariffs are different for the two groups. For

example, in assessing overall impact of trade policy changes it is best to examine the

effects through both nominal tariff rates and ERPs. A final potential conceptual problem

is that tariffs may not be linear in their effects, that is to say, there may be either declining

or (more likely) increasing marginal protection effects as tariff rates rise. In either case,

the effects of reducing tariffs will be nonlinear also and measures based on the levels of

tariffs will not capture this.

Thus, while these are the most direct measures of trade restriction available, I

caution against relying, at least solely, on them. As noted, the measures are far from

perfect and, in addition, other policy actions are important in determining the pattern of

trade. Tariff-based measures might work well in combination with other measures, but

this has yet to be shown.

4.5

Non-Tariff Barrier Measures

As tariff levels have declined (at least on manufactured goods) during the various

GATT rounds, non-tariff barriers (NTBs) have become increasingly important (Bhagwati

(1988), Edwards (1992)). These are policies other than tariffs that alter, directly or

indirectly, the prices and/or quantities of traded goods and services. Official (i.e.

mandated or legislated by the government) NTBs come in a wide variety of forms: import

quotas, voluntary export restraints, government procurement and domestic content

provisions, restrictions on services trade, trade-related investment measures,

administrative classification, etc. They also come in forms that do not appear to be

"barriers" to trade but rather serve to stimulate trade (at least from a domestic viewpoint)

such as export subsidies.

Not all forms of NTBs are "official" barriers, they may also arise from other

sources. Market structures vary across countries and national governments differ in how

much they promote competition. In some cases there is extensive government

involvement in industry, often allowing extensive collusion among firms or creating

government monopolies. This is viewed internally as domestic policy though it has

44 For example with imported beers, wines, cheeses, etc.

20

implications for the international trade policy of the country. Another, more contentious,

source of barriers are the cultural, social, or even political institutions operating within a

country. For example, countries such as Japan and Korea allow intricate relationships

among firms (the keiretsu and chaebol, respectively) across industries that would not be

found in a country such as the U.S. (indeed, would be illegal in the U.S.) and these in a

very real sense create trade policy on their own. The effects of these forms of trade

protection are more difficult to assess than the official NTBs.

The imperfections of NTBs as indicators of protection are well-known and are

larger than those of the tariff measures. To begin with, one has to identify or define the

barriers, which is difficult as NTBs are generally not transparent in either implementation

or operation. Deardorff and Stern (1997) note "A basic difficulty in approaching NTBs is

that they are defined by what they are not. That is, NTBs consist of all barriers to trade

that are not tariffs."45 The creation of a summary measure of NTBs would require the

inclusion of all of NTBs, otherwise the measure will make trade look freer than it is.

Unfortunately many NTBs, particularly the unofficial ones, are hard to identify or

measure and thus cannot be included. Furthermore, given the diversity of NTBs it is

difficult to put information about each of them in a format that is comparable across

them. Consider NTB coverage ratios, which are estimated as the percentage of imports

covered by these types of trade barriers. Counting the frequency of NTBs suggests the

existence of trade barriers but does not capture their effects. Different policy instruments

(say quotas, domestic content requirements, and customs regulations to name just a few)

will have different effects. The impact (intensity) of NTBs is not related to the number of

them but to the enforcement of them, which can vary from non- to strict enforcement.

Aggravating the problem is that the most effective barriers, which are prohibitive (or

close to), receive little weight in the estimations. Thus, coverage ratios for non-tariff

barriers are both difficult to calculate and understate effects of such barriers.46

To sum up, NTBs are poor indicators of trade restrictions both because broad

coverage by NTBs does not necessarily mean a higher distortion level and (as always)

there are difficulties of estimation because of data limitations. Edwards (1992) notes

"...NTB is likely to be one of the poorest indicator of trade orientation." Thus these

measures are often excluded from empirical studies. Ultimately, these measures are more

useful for identifying the existence of barriers to trade than for measuring them.47

4.6

Composite Indices

45 p.4.

46 An additional problem that likely occurs is that the effects of one NTB may affect the performance of

another NTB, which further weakens the idea that NTB measures can simply be added up to get a summary

measure.

47 It is worth noting that the exchange rate regime of a country can serve as a NTB. An overvalued

currency works against exports, as it has the same effect as an export tax, which in the case of developing

countries frequently implies both industrial protection and a bias against agriculture. Manipulating the

exchange rate directly is not the only way to use the exchange rate as a NTB. Capital controls, in the form

of foreign exchange allocations, can serve as a constraint on imports and governments can also ration

foreign currency, favoring certain industries or firms to the detriment of other sectors of the economy.

21

This category contains measures based on subjective evaluations of trade barriers,

structural characteristics, and institutional arrangements. As noted by Baldwin (2002,

p.27) high barriers to trade are very frequently found in conjunction with poor

macroeconomic policies, corruption, and unstable governments. In recognition of this a

number of indices that combine various indicators (such as macroeconomic, exchange

rate and educational indicators in addition to trade openness and policy indicators) into a

single variable have been developed. Researchers considering using composite indices

should become familiar with the components as well as the data on which the indices are

based prior to deciding to use one, in order to ascertain that the chosen measure captures

features important and not features immaterial to their models. Examples of two very

widely used indices are presented here.

The first of these is the World Bank's Outward Orientation Index.48 Examining

effective rates of protection, the use of direct trade controls and export incentives as well

as the degree of exchange rate overvaluation, the World Bank classified 41 LDCs for the

periods 1963-1973 and 1973-1985 into four categories: strongly-outward oriented

economies (rank = 1 in the data), moderately-outward oriented economies, moderatelyinward oriented economies, and strongly-inward oriented economies (rank = 4).

Strongly-outward oriented economies were characterized as having few controls on trade

and a currency that was neither over- or undervalued, moderately-outward oriented

economies had relatively low ERPs and bias in the exchange rate as well as only slight

biases against production for export, moderately-inward oriented economies favored

production for the domestic market through relatively high protection and an exchange

rate regime that discouraged exports, and strongly-inward oriented economies exhibited

comprehensive incentives toward import substitution.

The Bank's much-cited analysis found strong support for the claim that outward

oriented countries grew faster than inward oriented countries. Subsequent research

appeared to strengthen the conclusion. Greenaway and Nam (1988) showed that

economic performance progressively improved as countries moved from strongly inward

oriented stances to strongly outward oriented ones. Alam (1991) found the Bank's

measure of trade orientation to be positively associated with subsequent gains in real

GDP per capita.

As with all measures, there are concerns. Clearly there can be a large degree of

subjectivity in these assessments. Problems arise in coding data uniformly across

countries. Coding data often requires that judgments be made about the impacts of

different types of policies in different countries. This is a highly subjective exercise and

the results can be highly dependant upon who codes a particular country. Even with a

well-defined protocol applied by coders trained to assess data from different countries in

a consistent manner, judgment bias can occur and comparability of measures across

countries (and even for the same country over time) may be suspect.

In my judgment the orientation index is useful for ranking countries in relative