Case 1 | Bulletin 20 – General

Published January 2014

For archived bulletins, learning reports and related background

documents please visit www.ipcc.gov.uk/learning-the-lessons

Email | learning@ipcc.gsi.gov.uk

This document is classified as NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED in accordance with the IPCC’s protective marking scheme

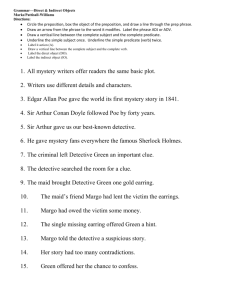

Control of a detained person

Arrest of a person suspected of involvement in drugs importation, raising issues about:

Working with other forces.

Carrying out and documenting risk assessments.

Supervisor roles in relation to risk assessment.

Selecting a location to detain a suspect.

Keeping suspect under constant supervision.

Use of personal protective equipment.

Location of post incident procedures.

Providing identity protection for officers involved in a death following police contact.

Overview of incident

Officers attempted to arrest two men after they left a property late one evening. A vehicle was

pursued and the two men were eventually both detained and arrested. One of the men was

found to have been carrying a bag containing a kilogram of cocaine.

Subsequent mobile phone analysis showed that the men had been in recent contact with a

phone belonging to Mr A. Officers researched the address that the men had been seen leaving,

and later attended the property to arrest Mr A and Ms B in connection with the supply of class A

drugs.

Officers took Mr A into the kitchen, where he was arrested by Detective Constable C. Mr A was

not handcuffed and sat in a chair at the kitchen table for approximately two hours while officers

searched his property.

As a result of his arrest, Mr A was interviewed and conditionally bailed with an electronic tag

and subjected to a curfew. He was later charged with ‘being concerned in the supply of class A

drugs’ and a date was scheduled for him to appear at Crown Court, for trial, together with the

other two males seen leaving his house.

Although he had been charged, the investigation into Mr A’s activities continued.

Intelligence was later received, linking Mr A to a smuggling attempt.

After further work, officers were able to obtain substantial evidence which suggested that Mr A,

together with his daughter, Ms D, and another man, Mr E, were pivotal in a drugs importation

network.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 1 of 22

On viewing this new evidence, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) advised that all three

suspects would need to be arrested for the importation offence before the trial, as it was clear

there would be an impact on these proceedings and the date may need to be changed.

Detective Constable C began planning the arrests, which were now scheduled to take place a

week before Mr A’s trial. Part of the strategy was for none of the three suspects to be informed

of the other arrests.

The plan was for each arrest team to be in possession of a Section 8, Police and Criminal

Evidence Act (PACE), search warrant to allow them to force entry to properties and recover

items specified on the warrant, if any of the suspects were not at home.

The key evidence outstanding in the investigation was a mobile phone used to contact the

couriers and a computer which had been used to book flights.

Taking into consideration the intelligence concerning Mr A, his conviction history, his age,

physical appearance and their recent contact with him, Detective Constable C assessed the

threat posed by Mr A to officers and himself as low. A similar risk assessment was carried out

for Ms D and Mr E who lived at separate addresses, and again the risk was assessed as low.

Detective Constable C did not conduct a formal documented risk assessment on any of the

suspects or their addresses, and neither he nor Detective Sergeant F considered there to be a

risk connected to the change in offence for which Mr A was to be arrested. Detective Sergeant

F also felt that the risk associated with Mr A had not changed since he was last arrested.

At the conclusion of his research, Detective Constable C produced three briefing packs, one for

each team making the arrests. The packs contained photos, maps and a brief background note

relating to the operation. Although the risk was deemed low, all officers were reminded to wear

their personal protective equipment (PPE).

On the morning of the day the arrests were due to be carried out, a briefing took place for the

teams that were due to be involved in the arrest. Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant

F ran through the aims and objectives for the day, the low risk associated with each address

and reiterated that none of the suspects were to be informed of the other arrests. Detective

Sergeant F also requested each team establish an arrest incident log before leaving.

Due to their previous dealings with Mr A, Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant F

decided they would attend his address. Before leaving, Detective Sergeant F asked Detective

Constable G, who was on the telephone setting up her arrest incident log for Ms D, to add the

place where they were going to arrest Mr A.

The operator informed Detective Constable G that the address was located in another force

area. She relayed this information back to Detective Sergeant F who stated he knew that to be

the case and so requested the incident record be sent through to the other force.

Detective Constable G relayed this information to the operator who generated an incident

record number, which was passed to Detective Sergeant F.

At around 7am, Detective Constable G and her team attended the first known address. Ms D

was not at home, but officers were able to obtain a contact number for her. When speaking to

Ms D, on the phone, the officers told her they wished to see her and asked her where she was.

The officers then made their way to her location.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 2 of 22

When officers arrived at her location, they arrested Ms D for conspiracy to import class A drugs.

The arresting officer conducted a dynamic risk assessment and decided not to handcuff her.

She was then taken back to her known address before the property was searched. After this

was completed, she was transported to the local police station.

Around the same time, Detective Constable C, Detective Sergeant F, Detective Constable H

and Detective Constable I arrived at Mr A’s property.

On arrival, Detective Constable H and Detective Constable I put on their stab protection body

armour and ensured they were in possession of personal protective equipment such as CS

spray, batons and handcuffs.

Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant F did not wear their body armour when they

entered the address. Detective Constable C also took a pair of handcuffs and a radio, while

Detective Sergeant F carried a baton and a pair of handcuffs.

Shortly after knocking on the door, Detective Constable I noticed Mr A looking out of a bedroom

window.

Detective Constable I identified himself as a police officer and asked Mr A to come down from

the bedroom. Mr A opened the front door completely naked and appeared to recognise

Detective Constable C from their previous dealings.

Detective Constable C informed Mr A that they had a warrant to search his house and Mr A

allowed them in without discussion.

Mr A appeared calm. When the officers asked him to put some clothes on he indicated he had a

dressing gown hanging on a door and was escorted by Detective Constable C to fetch it from an

upstairs bedroom.

Detective Constable H searched the dressing gown before it was handed to Mr A.

Mr A was then taken downstairs and sat in the dining area of the kitchen where the warrant was

explained to him. Detective Constable C then arrested Mr A for conspiracy to import class A

drugs into the UK, and cautioned him. Mr A did not respond.

Detective Constable H sat opposite Mr A at the table and made a note of the arrest in the

search log. Mr A was then asked to sign next to the note of his arrest, but declined to do so,

saying he would like to speak to his barrister first.

Detective Constable C conducted a dynamic risk assessment of the situation taking into

consideration Mr A’s physical build, the fact he was barefoot, naked under his dressing gown

and sat at a table. Mr A was compliant with all requests and had never acted in a violent or

confrontational way. Detective Constable C therefore assessed the likelihood of him becoming

violent as low. As a result, Detective Constable C felt that handcuffing him was an unjustified

use of force in the circumstances.

There were no knives or weapons visible and although they were sat in the dining area of a

large kitchen, Detective Constable C was comfortable as it was the same place Mr A had sat

when they had searched the property previously without incident. He did not believe Mr A was

an escape risk or posed a physical risk to himself or the officers.

Officers asked Mr A whether there were any firearms, drugs or large sums of money in the

house, to which he replied, “No”.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 3 of 22

Detective Constable H had a general conversation with Mr A and he told the officers he initially

thought they were visiting about the recent burglary at his house. They explained this was not

the case and they were there for the drug related matters that he had been arrested for.

Mr A had reported a burglary at his house to local police the previous week. During the burglary,

thieves reportedly stole the keys to three expensive cars parked at the house. These cars were

subject to a restraint order in relation to the supply of drugs offence, which meant they could not

be sold and were to be seized under the Proceeds of Crime Act. Detective Constable C was

unaware of the burglary and found it strange that only the keys to the vehicles had been stolen.

Around this time, Mr A asked to make a telephone call but this was declined by the officers. He

was told he would be taken to the local police station at the end of the search and he could

make a call from there.

Mr A informed the officers that he had a meeting with his barrister later that afternoon. Detective

Constable C recalls telling Mr A that there was lots of time left to get him interviewed and out,

but if they felt he was not going to make it, they would contact his barrister. This did not affect

his demeanour, he was content with the response and remained laid back and calm.

Detective Constable C wanted to build a rapport with Mr A and play-down the significance of the

arrest so chose not to make him aware that the CPS were likely to be charging him with

conspiracy to import class A drugs.

As he had just woken up, Mr A asked Detective Constable C and Detective Constable H if he

could have a cup of herbal tea.

Detective Constable H remained sat at the table but looked up from his paperwork. Detective

Constable C checked the work surfaces to ensure they were safe, before allowing Mr A to make

a cup of tea under his close supervision. After making the tea, Mr A thanked the officers, smiled

and returned to his seat.

During the previous search of Mr A’s home, he had been allowed to make himself cups of tea,

and Detective Constable C did not see why he should not be afforded the same courtesy on this

occasion.

Some time later Detective Constable I came into the kitchen and informed Detective Constable

H that he had started seizing exhibits.

Shortly after Detective Constable C received a phone call confirming that both Ms D and Mr E

had been arrested. Detective Constable C stepped out of earshot into the living room to take

this call, and Mr A remained unaware that the arrests had taken place.

Detective Constable C returned to the kitchen and after being happy with Mr A’s demeanour,

left him with Detective Constable H and went into another room to begin searching.

A few minutes later, Detective Constable I returned to the kitchen area and gave the evidence

he had found to Detective Constable H. While he was in the kitchen, Detective Constable H

asked him to remain with Mr A while he went and drew a sketch plan of the house in the search

log.

Mr A looked at the exhibits on the table and asked Detective Constable I what documents he

had seized. Mr A asked why he had taken these documents and Detective Constable I

explained that in matters of this type they were interested in company and financial documents.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 4 of 22

Detective Constable H returned to the kitchen and Detective Constable I asked him if he wanted

his body armour taken back to the car. The house was very warm and both officers decided Mr

A did not pose a risk warranting them keeping their personal protection equipment on.

Detective Constable H started entering the evidence from Detective Constable I into the search

log. Detective Constable I took their body armour to the car before going back upstairs to

continue searching. Detective Constable C was still in the study and Detective Sergeant F was

searching upstairs.

Detective Constable I found various items of interest in one of the bedrooms, including a laptop

computer, a mobile phone and a quantity of drugs.

Mr A’s daughter, Ms J, arrived just after 8am.

Detective Constable C opened the front door and identified himself as a police officer. He did

not tell Ms J that Mr A was under arrest or let her in the house.

Ms J then spoke to Mr A briefly before leaving the property.

Detective Constable H and Mr A then returned to the kitchen.

Once back in the kitchen, Mr A asked Detective Constable H if he could make another cup of

tea and have some biscuits. Detective Constable H agreed, and watched him make the tea from

his position sat at the kitchen table. Mr A also took a packet of biscuits from the cupboard

before returning to his seat.

The officer joked with Mr A that he must like his tea as he was drinking from a very large mug,

to which Mr A nodded in agreement as he was eating. He ate several biscuits before returning

the packet to the cupboard.

Detective Sergeant F took the items he had seized from the living room into the kitchen, where

he recalls Mr A was sat in the same position as earlier with a full mug of tea. He then left the

kitchen and went upstairs to search some of the bedrooms.

After making a phone call about the seizure of the cars, Detective Constable C went upstairs

and joined Detective Constable I who had identified several items of interest. Detective

Constable C sealed these items in evidence bags and took them down to the kitchen.

Detective Constable H remained at the kitchen table, entering the seized items into the search

log. The officer asked Mr A if the computer and the phone he had seized were both his, and he

replied that they were.

A short while later, Mr A admitted that the substance officers had found in the bedroom was

drugs, and he was further arrested by Detective Constable C for possession of cannabis.

Detective Constable C then asked Mr A about his car keys that he said had been stolen in the

burglary the week before. Detective Constable C went outside and checked the cars, which he

found to be unlocked. He found it strange the cars were still there as he would have expected

them to have been stolen when the car keys were taken.

Detective Constable C returned to the kitchen and discussed the burglary with Mr A. Detective

Sergeant F also entered the kitchen during this conversation and began searching through

some paperwork.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 5 of 22

During this time, Detective Constable H continued to enter the items into the search log. Mr A

remained polite and calm which was a continuation of the relaxed manner between them.

Detective Constable C stepped outside the house to make a phone call to his office regarding

the burglary. Shortly after, he returned inside, collected the search kit from the hallway and took

it out to his car.

While he was doing this, Detective Sergeant F went into the study opposite the kitchen. At the

same time, Detective Constable I had finished upstairs and came downstairs, where he recalled

Mr A being sat calmly in the same position as before. He then took this moment to step outside

the house to get some fresh air.

Detective Sergeant F had a quick look around the study before going outside to look at the cars

in the garage for himself. As he did so, he remembers glancing into the kitchen and seeing Mr A

leaning back in his chair with his mug of tea in front of him.

Detective Constable H was aware they were coming to the end of the search, as the other

officers had stopped bringing items down to the kitchen.

At this point, Detective Constable H noticed out the corner of his eye that Mr A was standing up

with his back to the fridge.

Detective Constable H recalls that Mr A appeared to bend to his left and then immediately stand

upright, and as he did so, Detective Constable H noticed he had an object in his right hand.

Detective Constable H then looked up properly and was not initially concerned because

throughout their time in the property, Mr A had never presented himself to be a threat.

Mr A was now stood facing Detective Constable H with both his arms open to the side at

shoulder height. Detective Constable H then noticed that Mr A was holding a large knife.

Detective Constable H shouted “knife!” to warn his colleagues. Detective Constable C had reentered the property and was making his way down the hallway to the kitchen when he heard

shouting. He could not initially make out the words but then heard Detective Constable H shout

and knew he needed assistance.

Detective Constable H recalls that Mr A then threatened officers with the knife, and that his

body language had completely changed, he now looked very angry and screamed at the

officers.

As he was screaming, Mr A plunged the knife into his chest.

As he was swinging the blade round, Detective Constable H recalls shouting “Stop! No!” and

stood up from his chair with his arms raised, showing the palms of his hands in a passive

gesture.

He then ran around the table towards Mr A, while at the same time shouting to colleagues to

call an ambulance. Detective Constable C arrived in the kitchen around the same time.

Detective Constable C recalls running into the kitchen and noticing the chair where Mr A had

been sitting was empty. Turning to his left he almost bumped into Mr A who appeared enraged

and was shouting.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 6 of 22

Detective Constable H could see the knife was embedded in Mr A’s chest. Mr A then let go of

the knife and raised his hands out to the front in a grabbing motion, making an angry roaring

noise as he did so. He lunged towards both the officers and they instinctively grabbed one arm

each.

Mr A remained on his feet and was fighting against the officers, moving both his arms and trying

to grab the knife.

Hearing the shouting, Detective Constable I made his way to the kitchen. He saw Detective

Constable C and Detective Constable H struggling with Mr A, who was making a growling type

noise and facing towards the table with both his arms raised.

Detective Constable I recalls Mr A’s right profile was slightly turned towards him and he could

clearly see the dark handle and wide back end of what he believed was a knife protruding from

Mr A’s chest. He was shocked at what he saw and it took a few seconds for him to realise what

was happening.

Realising an ambulance was needed urgently, he turned to get his phone, which was in the

pocket of his jacket by the front door. As he did so, Detective Sergeant F appeared in the

hallway behind him and Detective Constable I said “Get an ambulance, he has stabbed himself

in the chest,” followed by, “Give me some handcuffs”.

Detective Sergeant F recalls running through the front door and hearing the shout, “knife”.

When he fully entered the kitchen, he noticed blood on the floor and Detective Constable C

pulling Mr A to the floor while having difficulty holding his arm. Although he was aware Detective

Constable H was shouting, he had not taken in what he was saying and had not yet seen the

knife.

As Detective Constable C was taking Mr A to the floor, Detective Constable H was shouting at

him, “He’s got a knife in his chest; he’s got a knife in his chest!”. Detective Constable H held

onto Mr A’s right arm, almost holding him up and shouted, “Stop struggling we’re trying to help

you.”

Mr A went down in a controlled fall onto his left side with his head very close to the corner point

of the kitchen units. He continued trying to grab the knife and Detective Constable C shouted for

handcuffs. Detective Constable H recalls it being only a matter of seconds from the moment

they took hold of him to the moment he was laying on the floor.

As Mr A went to the floor, Detective Sergeant F took out his mobile phone and dialled 999.

An ambulance was called and officers attempted to administer first aid.

Shortly after the ambulance crew entered the house, Police Constable K from the local force

arrived and was met outside by Detective Constable I and Detective Sergeant F.

Detective Sergeant F stated that he wanted to speak to the duty inspector from the local force

and Police Constable K put them in touch. He also started a scene log, recording everyone who

went in and out of the address.

The local force duty inspector that day was Inspector L. After speaking to Detective Sergeant F,

he made his way to the scene.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 7 of 22

Shortly after, Ms J arrived back at the property. On arrival, she was met by Police Constable K

who informed her that she could not go in, so after asking what was going on and being told

nothing, she sat back in her car and awaited information.

Mr A died later of his injuries.

More officers from the local force arrived at the house and arrangements were made for

Detective Constable C, Detective Sergeant F, Detective Constable H and Detective Constable I

to be taken to a local police station for a post incident procedure.

During this process each of the four officers gave an initial written account of the events. These

were thorough and in line with the guidance. They were also examined for injuries by a forensic

medical examiner. None of the officers had any fresh injuries. They were also photographed

and blood staining on their bodies and clothing was recorded. The clothing from each of the

officers was forensically taken and subsequently retained by the IPCC.

Approximately two weeks after the incident, the four officers provided further detailed accounts

via their solicitors. Although asked to be interviewed as a significant witness to Mr A’s death,

Detective Constable H declined.

In the early afternoon, scenes of crime officers from the local force began the forensic

examination.

A Home Office forensic pathologist attended the scene and examined Mr A’s body in situ,

before his body was then moved to the mortuary at the local hospital for a post mortem

examination.

Officers from the local force provided a cordon to secure the scene throughout the night.

Type of investigation

IPCC independent investigation.

Findings and recommendations

Pre-operation

Finding 1 – Passing of information

1.

The operator in the control room was told by Detective Constable G that Mr A’s home

was within another force area.

2.

Detective Constable G requested the operator inform the local force of their intention to

conduct a cross-border operation. The local force had no record of receiving this

information.

3.

The processes and systems are already in place for cross-border liaison and there are

no recommendations to change them. It is likely that on this occasion, the failure to pass

on information was due to a breakdown individually or locally within the control room.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 8 of 22

Local recommendation 1

4.

Checks should be made with the control room to see where the liaison between the two

forces broke down.

Local recommendation 2

5.

Officers in charge of cross-border operations should ensure they are in possession of the

incident log reference raised by the host force before deploying officers.

Finding 2 - Obtaining information for the risk assessment

6.

When planning the arrest and search of Mr A’s home, Detective Constable C did not

conduct any checks with the local force’s Intelligence Bureau.

7.

He was therefore unaware that Mr A had reported a burglary at his home the week

before the search, during which he stated the keys to three expensive cars (which

Detective Constable C was hoping to seize) had been stolen.

8.

As a result of the burglary, an officer from the local force visited Mr A’s home and would

have been in an ideal position to provide current details that would have been pertinent

to the risk assessment and planning of the operation.

Local recommendation 3

9.

Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant F should be reminded of the importance

of contacting the host force’s Intelligence Bureau as part of the risk assessment process.

Supervisors overseeing cross-border operations should ensure this has been done.

Local recommendation 4

6.

It is recognised that on some occasions, the host force’s Intelligence Bureau will not be

contacted for operational reasons, however, if this is not carried out, the reason should

be documented.

Local recommendation 5

7.

Contact with the host force Intelligence Bureau (for cross-border operations) should form

part of the check list in the Risk Assessment Aide Memoire contained within the force’s

Search Log. This document should also contain a supervisor’s approval section which

would ensure a supervisor had seen and agreed the risk assessment.

Finding 3 - The application of Section 8 PACE search warrants

8.

Detective Constable C applied for three Section 8 Police and Criminal Evidence Act

(PACE) warrants, one of which was for the search of Mr A’s home address. The warrant

obtained was not an all-premises search warrant and did not include the three vehicles

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 9 of 22

that Detective Constable C stated he wanted to search before seizing them under the

Proceeds of Crime Act.

9.

Section 32, PACE, allows for the search of premises where a person is at the time of, or

immediately prior to, arrest. As the officers stated they believed he had just got out of

bed, they could not have relied on this power to search these vehicles.

10.

Under PACE, vehicles are premises in their own right and therefore must be individually

listed for the purposes of a Section 8, PACE warrant application.

Local recommendation 6

11.

Detective Constable C and the supervisor responsible for approving search warrants,

should be reminded of the law in relation to Section 8 PACE.

Local recommendation 7

8.

In addition, to ensure this is not a wider problem within this police unit, it is recommended

that a dip sample of Section 8 PACE warrants covering the past 12 months is conducted.

The results of the dip sampling may identify that wider learning is required.

Assessing risk

Finding 4 - Documenting the risk assessment

9.

There is no evidence of a documented risk assessment and the Search Log Risk

Assessment Aide Memoire had been crossed through as ‘N/A’.

10.

According to the force’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) on the Investigation of

Crime (Secondary), the Search Log Aide Memoire must document the risks associated

with the search.

Local recommendation 8

11.

It is understood that in operational policing, there is not always time to document a risk

assessment. However, where time does permit, as in this case, documented risk

assessments must be completed. These do not necessarily need to be lengthy but

should be focused on the activity they relate to and demonstrate that a range of risk

factors have been considered and managed.

Local recommendation 9

12.

Detective Constable C must be reminded that documenting risk assessments before an

operation is essential. If this is not carried out, a conclusion is likely to be drawn that a

risk assessment was not carried out.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 10 of 22

Local recommendation 10

13.

Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant F should be made aware of the SOPs in

existence for the completion of a documented risk assessment before a search of a

property.

Local recommendation 11

14.

Detective Sergeant F should be reminded of his responsibilities as a supervisor to ensure

the risk assessment is comprehensive and documented before deploying for a search of

property.

Local recommendation 12

15.

Other specialist units within the force record risk assessments against pre-defined

templates held locally on a computer database. A check should be conducted to

establish if such templates exist within this police unit.

Local recommendation 13

16.

If predefined templates for recording risk assessments do exist, clarification must be

sought within the force, as to where officers are expected to record the risk assessment

before searching premises – in the Search Log (as per SOPs) or on the templates.

17.

If the force want risk assessments relating to property searches to remain in the Search

Log, the Search Log Risk Assessment Aide Memoire should be modified to make it more

comprehensive and easier to use. Or, if the force want risk assessments relating to

property searches to be conducted using computer-held templates only, and not be

completed in the Search Log, existing templates must be validated to ensure they meet

the business need they were created for. If they do not exist, a structured template

should be created and held on the local computer system to allow for risks associated

with searching properties to be identified and assessed easily. The Search Log Aide

Memoire and this page should then be removed from the Search Log.

18.

The SOPs contained within the SOP for the Investigation of Crime (secondary) must be

updated to reflect the change in procedure.

Finding 5 - Identifying risk factors and grading risk

19.

The risk assessment conducted by Detective Constable C before this operation was not

adequate in that when assigning the risk, he did not consider anything other than the

physical risks. There was no consideration given to the psychological risk associated with

the arrest of Mr A.

20.

There was no consideration given to any unpredictable behaviour of the suspect.

Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant F felt they ‘knew’ Mr A because of their

previous dealings with him.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 11 of 22

21.

Detective Sergeant F, the supervisor, did not believe the risk associated with Mr A had

changed since the last time they arrested him the previous year. Detective Sergeant F

was not in a position to make this judgement as he did not have any current knowledge

on Mr A’s lifestyle or the occupants of his home.

22.

The offence that Mr A was arrested (conspiracy to import class A drugs) was more

serious than the previous offence (conspiracy to supply class A drugs). Mr A was also on

bail and being monitored by an electronic tag, therefore he was unlikely to be bailed

following this arrest. Mr A is likely to have known this.

23.

All of these factors increased the psychological risk to Mr A.

24.

Detective Constable C’s grading of the risk was ‘low’, a grading which is not officially

used in the force.

Local recommendation 14

25.

Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant F should be re-trained on identifying and

managing risks.

Local recommendation 15

26.

The current Risk Assessment Aide Memoire contained in the Search Log is not adequate

for officers to conduct and document concise risk assessments. Currently there is a free

text box for identifying and managing risks, which although is necessary, it is

recommended the use of a risk model is incorporated into the Aide Memoire to assist in

structuring assessments.

Local recommendation 16

27.

An officer should never base their risk assessment of someone solely on the fact they

have arrested someone before. All suspects should be treated as an unknown risk. The

modification to the Aide Memoire must include a section to show the assessor has

considered unpredictable behaviour by a suspect.

Local recommendation 17

28.

It is recommended that an ‘approval’ section is incorporated into the risk assessment to

ensure a supervisor has seen and approved the assessment.

Finding 6 - Officer safety and control of a detained person

29.

When they entered his home, Mr A was taken to the kitchen and arrested. He was not

handcuffed and remained sat in this area at a table opposite Detective Constable H, who

was filling in the Search Log.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 12 of 22

30.

After a short while, Detective Constable H and Detective Constable I removed their

safety equipment to their car.

31.

As the officer left to supervise Mr A, Detective Constable H sat in a position that

prevented him from having a good level of control over Mr A. He was situated in between

the kitchen table and the kitchen French doors, meaning that if Mr A decided to use

violence against this officer, he would be unable to defend himself or get out of the way.

32.

At the start of the search, Mr A made himself a cup of tea under supervision from

Detective Constable C who stated he did not feel this was a risk as they had afforded him

the same courtesy when they arrested him previously.

33.

Towards the end of the search, Mr A asked if he could make another cup of tea. On this

occasion, Detective Constable H observed him from his seated position make a cup of

tea and get some biscuits on the other side of the kitchen.

Local recommendation 18

34.

There is no recommendation made over the fact Mr A was not handcuffed. Exerting

control over a suspect does not always require the use of handcuffs and should be

judged on a case-by-case basis in line with officer safety training and handcuffing SOPs.

35.

All operational officers should be reminded of the following:

Suspects must always be detained in the safest room of the house. This is the part

of the house which negates the risk of harm to the officers and suspect. Kitchens

must therefore (generally) be avoided at all times.

A suspect may have weapons concealed in their homes and therefore, once

detained, they should not be allowed to freely move around and should remain in

one location, e.g. sat on the sofa, which should be searched prior to them sitting

on it.

Suspects must remain under constant supervision.

If a suspect requests refreshments they must never be allowed to make them

themselves.

On every search, one person should take responsibility for the safety of the search

including the suspect(s), officers and the environment.

Only if absolutely necessary, and after the premises and occupants are under

control, should consideration be given to the removal of safety equipment.

The situation should never arise where there is no protective equipment available

to officers who have a detained person who is not handcuffed.

Thought must be given to where officers position themselves to maximise their

safety and the control they can exert over a suspect. This is heightened if the

suspect is not handcuffed.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 13 of 22

36.

All of the above should be factored into officer safety training or the most appropriate

course delivered by the force to operational staff.

37.

Consideration should be given to using this scenario for training purposes.

Local recommendation 19

38.

All the officers involved in the search of Mr A’s home must be debriefed on the learning

from this investigation.

Local recommendation 20

39.

All existing staff in this police unit should be informed of the learning coming from this

case.

Finding 7 – Officer safety equipment

40.

Despite making a note in the briefing packs that all officers involved in the operation

should wear their personal protective equipment, Detective Constable C and Detective

Sergeant F, the team sergeant, approached Mr A’s property without stab proof vests.

41.

Their attitude towards the risk to themselves was partly because they knew Mr A through

their previous dealings with him.

42.

Detective Constable H and Detective Sergeant F wore stab proof vests and had their

personal protective equipment (PPE) as per the briefing.

Local recommendation 21

43.

All officers and staff who attend search operations must deploy with the appropriate

personal protective equipment and adopt the risk mitigation measures identified following

a suitable and sufficient risk assessment of the operation.

Local recommendation 22

44.

Suspects must always be treated as unknown risks no matter how many times they have

been dealt with previously by the police.

Local recommendation 23

45.

Detective Constable C should be reminded that if he outlines a control measure to a risk

during a briefing, he should follow it and set an example.

Local recommendation 24

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 14 of 22

46.

Detective Sergeant F should be reminded that as a supervisor he had a duty to ensure

both he and Detective Constable C were wearing their stab proof vests and that each

had adequate personal protective equipment.

Local recommendation 25

47.

Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant F must be reminded that a suspect

always presents an unknown risk no matter how many times they have been dealt with

previously.

Post incident

Finding 8 – Deciding on a location for the post incident procedure (PIP)

48.

There was confusion created by the force as to where the PIP was going to take place,

which in turn created a delay in IPCC attendance.

Local recommendation 26

49.

Once the location of a post incident procedure is decided this should not be changed as

it can cause significant delay to the start of the PIP and to the attendance of the IPCC.

Finding 9 - Identity protection

50.

At the beginning of the PIP, the officers who attended Mr A’s house demanded

anonymity from the IPCC.

51.

It appeared the officer’s compliance with the PIP was dependent on them obtaining this

status, and therefore a decision was taken by the IPCC to allow the officers to be given

pseudonyms for use at this time.

52.

Detective Constable C, Detective Constable H, Detective Constable I and Detective

Sergeant F did not want photographs taken of their faces.

Local recommendation 27

53.

Please note that this recommendation is not applicable following fatal firearms

incidents.

54.

The following points should be brought to the attention of Detective Constable C,

Detective Sergeant F, Detective Constable H and Detective Constable I and all

operational officers.

The IPCC can offer ‘identity protection’ where necessary to officers if they are

significantly involved in a death following police contact and if the IPCC believes

this a significant reason to do so.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 15 of 22

Protection of identity during an IPCC investigation simply means the officers

names will not be known to anyone other than the lead IPCC investigator.

Identity protection is not a given right and officers who normally operate in an overt

role using their real names, should not expect their names to be protected within

an investigation.

Officers who are merely trained in a covert role, such as conventional surveillance,

but operate in an overt role are unlikely to have their identity protected on this

basis alone.

Officers should not refuse to have photographs taken during a PIP process for the

purpose of safeguarding evidence and must understand this serves to protect

them as well as to progress the investigation.

Although subject to legal advice, the PIP should be open and transparent to avoid

public speculation of wrongdoing on behalf of the officers involved, especially in

cases of heightened sensitivity.

Officer’s identity is always safeguarded by the IPCC and subject to a harm test

before being disclosed to a third party.

The IPCC does not grant anonymity, this can only be given by the judge or a

coroner after consideration, and before any criminal or inquest proceedings.

Force response

Local recommendation 1

1.

The force’s final position remains that Detective Constable G contacted the control room

asking for an incident log to be sent relating to the arrest. However the force has been

unable to find any evidence that the message was sent and the local force maintain that

they did not receive it.

Local recommendation 2

2.

The risk assessment in the record of search booklet has been amended to require

incident log or equivalent incident reference numbers from both forces to be included for

any cross-border enquiry, proving that both parties have communicated with each other.

Local recommendation 3

3.

Detective Constable C and Detective Sergeant F were reminded about the importance of

contacting the host force Intelligence Bureau as part of the risk assessment process.

4.

The force notes that the incident arose in the context of a ‘cross-border arrest enquiry’,

not a pre-planned ‘cross-border operation’. As a result, there is a practical distinction

between the two. The term ‘police operation’ normally refers to a co-ordinated policing

activity involving a number of officers from one force, for which plans are necessary in

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 16 of 22

order to effectively carry out the operation. These plans may involve a document that

covers a wide range of areas such as briefing material, logistical information, times,

dates, command structure and responsibilities, radio call signs, officer details, contact

details, maps, plans, diagrams, and contingencies for various unforeseen eventualities.

For smaller, less comprehensive deployments, and especially in the case of fast-moving

spontaneous matters, the relevant details may be recorded in an officer’s pocket book or

other relevant document produced and maintained by the officer. The term ‘policing

enquiry’ would normally be associated with a smaller deployment that is conducted

without the need for detailed forward-planning. An enquiry of this nature may cover a

wide range of policing activities, from a search of a location, area or premises, either for

a person or for evidence, to no more than a knock on a door to see if a person is there. In

either case, it is expected that the host force would be informed of the activity and details

registered within the host force’s command and control system.

Local recommendations 4 and 5

5.

Following the incident, a decision was made that existing standard operating procedures

(SOPs) would be reviewed.

6.

Recommendations from the investigation have been incorporated into a new toolkit with

details about risk assessment methodology.

7.

The toolkit, condenses the most important aspects of policy into a handy check list (a

brief flowchart, or collection of bullet points, containing only the key information needed

by the operational officer), supported by more detailed contextual information, specific

forms to be used, and so on, optionally available as needed via hyperlinks from the main

toolkit.

8.

The toolkit also reminds supervisors of their responsibility to review risk assessments and

endorse the record with their signature.

9.

The record of search booklet already includes a section for a supervisor to complete. The

force will ensure that it remains a specific duty for a supervisor to read and approve the

risk assessment page or any document referred to in the record of search booklet. The

supervisor will be required to date and sign the physical risk assessment checklist page,

or otherwise endorse an equivalent document held electronically.

10.

Had officers contacted the local force’s Intelligence Bureau, before they attended the

scene, they would have seen Mr A’s earlier crime report of a burglary at his address.

They may then have noted that the person reporting the offence could not provide his

own telephone number to the reporting officer, a fact commented on by that officer.

Indeed, once officers arrived at the address and were speaking to Mr A, they did ring the

local control room to find out what the crime report stated. The information received as a

result of this enquiry however, had no bearing on their dynamic risk assessment of the

situation.

11.

Ideally, a search of all possible sources which might reasonably be expected to have a

bearing on a pre-planned police activity should have been carried out. This needs to be

balanced against other factors, such as the time a more detailed search for information

and follow-up enquiries might take, and the impact this delay may have on the police

activity.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 17 of 22

12.

Contact with the host force Intelligence Bureau is accepted as best practice. Non-contact

of the host force Intelligence Bureau would need to be accounted for in the new

procedures now in place as a result of the learning in this case.

Local recommendations 6 and 7

11.

The force does not agree with the legal position adopted by the IPCC.

12.

A vehicle may be searched if it is parked within the curtilage of premises covered by the

warrant. In that context it constitutes goods on the premises. As statute makes clear, a

vehicle may also be ‘premises’ in its own right under section 23 of PACE. It is suggested

that the IPCC may have taken an overly narrow view about the limits of the definition of

‘premises’ for the purpose of a search conducted under the authority of the section 8

warrant. This may be through a mistaken assumption that powers of search following

arrest under section 32 of PACE were being exercised, rather than under the authority of

a section 8 warrant. The Police National Legal Database is helpful here: “The lawfulness

of police conduct in the execution of a search warrant will often depend on the precise

wording of the warrant. By virtue of section 23 PACE, the term ‘premises’ includes,

amongst other matters, any vehicle, vessel and any tent or moveable structure. From this

it can well be argued that if the search warrant were to be couched in the terms of

‘authorised to search premises situate at …………. (specify address) ….’ the warrant

would authorise search of vehicles at that address, irrespective of who they might belong

to, as well as the dwelling itself.” (Source: D17273 / Search warrant - extent of power

[FAQ] )”

13.

It follows, that the suggested random ‘dip sampling’ of warrant applications would prove

ineffective unless sufficient resource-intensive ‘background’ was obtained for each case.

This would place the terms of any particular application in its correct perspective. It would

be more appropriate to ensure that there was effective supervisory oversight of all

warrants and warrant applications.

Local recommendation 8

14.

The existing search log already includes a Risk Assessment Aide Memoire. A short

response of ‘n/a’ (not applicable) may not be sufficient for many search activities in a preplanned situation. A brief entry to the effect that ‘no known risks are identified’ however,

may be defensible legally, depending on the circumstances, since this indicates that the

question of risk was considered and then set aside. This point has been addressed in the

unit through the development of an enhanced set of risk assessments.

15.

The risk assessment, which is featured in the new toolkit, includes specific reference to

its use in the search log, and includes further guidance to supervisors as to the kind of

written presentation they should expect to see completed where an authorising signature

is needed for risk assessing a premises search.

16.

A number of organisation-wide training courses on the proper conduct and documenting

of risk assessments for officers and staff in various ranks and roles are already in place.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 18 of 22

17.

The force describes risk assessment as a two-part process, with an initial written stage

during planning, and then, while the policing activity is occurring, the focus shifting to

dynamic risk assessment, supported by the skills and techniques offered through officer

safety training. However, if the officer believed, at the planning stage, that the subject,

the equipment being used, any materials present and the environment did not pose ‘a

significant risk’ there would be no need to record any specific risk assessment.

Local recommendations 9, 10 and 11

18.

The officers listed have been spoken to about the issues identified.

Local recommendation 12

19.

The force has developed an enhanced risk assessment which has been included in a

new risk assessment toolkit as part of the organisation-wide redrafting of standard

operating procedures.

Local recommendation 13

20.

The points raised during this recommendation have been incorporated within the

organisation-wide review of standard operating procedures and in the development of a

new risk assessment toolkit.

21.

Officers have the choice either to make amendments to risk assessments in the search

log or to maintain an electronic version. While the ‘standard’ hard copy search record is

suitable for many routine police search tasks, more specialist documents, perhaps

replaced by, or supported through, computer-held templates may be required for more

specialised or extensive searches undertaken by certain units. The form the

documentation takes is of less consequence than the fact a unique retrievable, auditable

document is completed in every case, and supervised by accountable, competent

individuals in accordance with the principles of nationally-recognised risk assessment

processes and risk assessment training. This issue will be addressed through the current

review.

Local recommendation 14

22.

The force has taken steps to ensure both officers continue to receive refresher training

as operational considerations permit.

Local recommendation 15

24.

The search log contains an aide memoire which addresses the issues raised within this

recommendation. This must be set against the potential further risk of an over-reliance

on rigid risk assessment models. For these reasons, a free-text area will always be

necessary in order to document and respond flexibly to the changing and inherently

unknowable aspects of a risk. This is also supported by the inclusion of an enhanced risk

model, contained within the online risk assessment toolkit. This will assist corporate

adherence to a single, upgradeable, best-practice risk assessment model across the

force.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 19 of 22

Local recommendation 16

25.

Current owners of the search log confirm that the risk assessment guidance within the

toolkit is consistent with force policy. It also provides an enhanced aide memoire within a

redesigned search log.

26.

The force is also reviewing recruitment and in-service training for officers, with a new

emphasis on identifying and responding proportionally to ‘vulnerability’ in a person,

regardless of the source of that vulnerability.

Local recommendation 17

27.

The search log already includes a section for a supervisor to complete. The force will

ensure that a supervisor continues to read through and approve the risk assessment

page or a similar document. The supervisor will then be required to sign, print and date

the risk assessment checklist page, or to confirm the status of any electronic counterpart

that has been authorised.

Local recommendation 18 and 19

28.

All the officers involved in the search of Mr A’s home have been debriefed on the

learning from this case. All staff working within this unit have also been informed of the

recommendations made during the course of the IPCC investigation.

Local recommendation 20

29.

The recommendation has been cascaded to all relevant officers.

30.

Where appropriate, this circulation has also been supported by further direction on

related matters. For example, in one unit, all current in-house training materials will,

when next due for review, be quality-assured against the eight points to ensure

compliance with the principles they set out.

31.

The investigation report has been forwarded to the lead for officer safety training to

consider including in future officer safety training interventions. It has also been

forwarded to the Curriculum Design team to consider including in any other relevant

courses.

Local recommendations 21 and 22

32.

The force believes that the existing principles of health and safety risk assessments and

dynamic risk assessments address these issues at the organisational level.

Local recommendations 23, 24 and 25

33.

The force has confirmed that the relevant issues have been brought to the attention of

the individuals concerned.

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 20 of 22

Local recommendation 26

34.

It is accepted that unfortunately in this case, in the immediate friction of events involving

three potential decision-making parties – the force, the local force and the IPCC – the

venue for the post incident procedure was changed. It is beyond question that a single

fixed location for post incident procedures is always to be preferred when possible. There

is therefore learning from this incident for the managers of all three organisations

regarding full communication between all parties at the earliest possible point. It is also

felt that it would be counter-productive to attempt to draw any general rule from this

specific incident, since circumstances will inevitably differ from incident to incident, and

possibly change during the course of an incident as new information is assessed. The

requirements of safety, effective investigation, and victim and witness care clearly must

always take precedence over choosing a venue merely because it was the one first

nominated. The siting and, if necessary, re-location of the most suitable venue for post

incident procedures must always remain a matter for the judgement and agreement of

the investigating parties in each case, while respecting that the immediate investigative,

operational, and safety demands of the incident remain the most important.

Local recommendation 27

35.

The force has brought the relevant points to the attention of the relevant officers.

36.

Regarding the suggestion that ‘all operational officers be made aware of the following.’

The force respectfully submitted that a general circulation outlining this, without the

context of an incident that immediately involves that target audience, may achieve the

opposite effect. By highlighting the possibility of requesting ‘identity protection’ from the

IPCC for all officers where possibility may not have previously occurred to the officers.

37.

Regardless of the internal measures employed by the IPCC in the granting of identity

protection, the officers concerned will also be entitled to seek Police Federation and legal

advice, in addition to taking the wishes of the IPCC into account. It follows that it would

be more effective for the IPCC to make the argument on this issue on a case-by-case

basis, as the appropriateness of a request for identity protection will always depend on

the particular circumstances of the case. For this reason, at present, no general

circulation on this point is envisaged.

Other action taken by this force

38.

This case has also been brought to the attention of the Training Sub Group of the Mental

Health Programme Board Initiative. Though still a work in progress, the Training Sub

Group is keen to ensure that new training inputs will draw on a number of relevant,

recent incidents. Although this work sits under the umbrella of ‘mental health’, it

incorporates a large-scale thematic review of all aspects of police interaction with

‘vulnerable’ people, regardless of the source of their vulnerability. An emerging strand of

the work is that standard officer safety and first aid training, both for recruits and serving

officers, in future needs to incorporate an awareness of how best to recognise and

interact with such ‘vulnerable’ people, whether their vulnerability is due to substance

abuse, mental or physical illness, permanent disability or, as it would appear in the case

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 21 of 22

of Mr A, emotional distress exacerbated by the situation. It is anticipated that some of this

training will be video or role play based.

39.

Additionally, a 'fast time' anonymised scenario based on the lessons of this case was

incorporated into the current round of officer safety training. In the next round of officer

safety training, a reminder will be included, which states that during any police encounter

or activity there are only ever two levels of risk: 'High' and 'Unknown'. Unknown means

this could be that the officers know certain things (such as a previous unproblematic

relationship with a subject) but they cannot know everything about a subject, and this

should mean they are thought of as an unknown risk. No subject should ever be seen as

low risk. We teach our officers to project calmness, achieve rapport, and exert effective

control. Regarding the 'Rapport' stage, it is accepted that this has a wider remit for

certain officers and roles and consequently, whilst they may wish to allow a subject more

freedom, for example during the course of a long search at a venue, they should still be

able to control them. We will re-enforce that a subject should never be seen as a low risk

and that if an officer makes a decision to allow a subject a certain amount of freedom,

such as not being handcuffed during a premises search, they would have to look at

controls, such as the guidance we circulated regarding a suitable, safe, and searched

location in which to detain the person, and an appropriate number of officers on hand to

safely manage the situation should the subject suddenly shift from 'unknown' to 'high' risk

for any reason.

Outcomes for officers and staff

1.

There were no criminal, disciplinary or misconduct outcomes for any of the police officers

or police staff involved in this case.

If you need more information about this case, please email learning@ipcc.gsi.gov.uk

© Independent Police Complaints Commission. All Rights Reserved.

Page 22 of 22