A FRAMEWORK FOR THE CLASSIFICATION OF ACCOUNTS

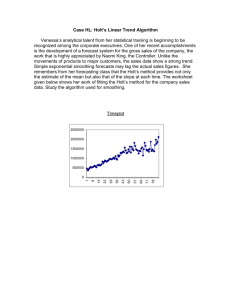

advertisement