La Mansión del Inglés - http://www.mansioningles.com THE

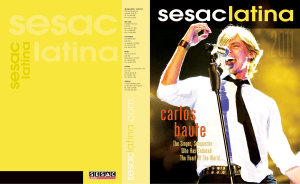

advertisement