CPD Spotlight Quiz September 2012 Working Capital

advertisement

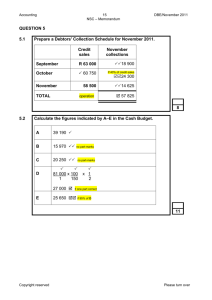

CPD Spotlight Quiz September 2012 Working Capital 1 What is working capital? This is a topic that has been the subject of debate for many years and will, no doubt, continue to be so. One response to the question is that it is the ‘ready cash that keeps the wheels turning’. Another might be the classic accounting definition of ‘current assets less current liabilities’. To start to answer the question ‘What is working capital?’ first we need to be clear what we mean by the term. We mean the investment that has to be made in the company in order for it to trade normally. For a manufacturer that means, the investment to buy and stock raw materials, to complete the manufacturing process and to be able to wait for the final customer to pay his invoice – the classic ‘asset conversion cycle’. So, we can sum that up as stocks plus debtors less creditors. Stock and debtors being the amount that we have to invest, the investment being partly offset by the fact that we don’t have to pay for all of it, some is held over as creditors. All of this is fairly basic stuff. The difficulty starts when we ask what the number is. Question 1 What is the best measure for the net investment in working capital? (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) All current assets less all current liabilities All current assets less only trade creditors All stocks plus all debtors less creditors All stocks plus all trade related debtors and creditors Don’t know Answer (a) The right answer is (d) All stocks plus all trade related debtors and creditors. Stock and debtors are fairly clearly part of the working capital cycle, sometimes called the asset conversion cycle, because they have to be incurred in order to do business. On the liability side the offsetting part of working capital is made up of those items that concern the trading cycle – in other words the unpaid trade debts. Most clearly this includes trade creditors. But we also need to include other items concerning the costs of raising raw material to either work-in-progress or finished goods. So we include accruals and other trade related items. What should be excluded is any item that relates to either short term debt, tax payments or dividend payments; these are not to do with the trading cycle, they are funding related or profit related. Payables for employee taxes however could be included as trade related. At the core of this issue is the distinction between working capital and the funding of that working capital. If we don’t get this clear then we will always be confused. Current liabilities – more strictly creditors due in less than one year – includes some items that are trade related and some that are funding related. 2 Funding working capital The problem with the traditional ‘current assets less current liabilities’ definition is that short term creditors’ includes a mixture of funding items and trade items. Take an example; a company asks for a loan to fund its working capital. The bank grants a short term loan and all is well. Has working capital increased? Current assets have increased because the company can now fund more stock and debtors. But the short loan is categorised as a short liability so it increases current liabilities. The net effect is that current assets less current liabilities remains the same – as long as all of the loan goes towards funding stock and debtors. So do we have more working capital? By the traditional measure, no we don’t! We know what has happened in reality, we do have more working capital and it is funded by the new loan. But what would happen if we spent some of the loan proceeds on longer term assets? This brings us to the next core issue of working capital – how should it be funded. Question 2 How should working capital be funded? (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) It is all about short assets and liabilities, so the funding should be short. We always need working capital, so it should be long term funding Term funding for the ‘permanent’ portion and short funding for the seasonal portion This is all theoretical – maturity doesn’t matter Don’t know Answer The right answer is (c) Term funding for the ‘permanent’ portion and short funding for the seasonal portion. The traditional answer is (a) hence the widespread use of the overdraft in the UK and short finance elsewhere. This can be very risky because short finance has to be renewed at maturity and circumstances may not make it easy to renew loans. In the UK, the overdraft is nominally repayable on demand – in other words it can be called at the first sign of trouble. Even if repayment could be managed, the cross default clause is very likely to trigger bigger problems. The key is to understand that working capital is a long term asset even though it is made up of recirculating short term assets and liabilities. Rather like a car hire company that always has cars less than a year old, each car is short term but the asset that is the hire fleet is there for the long term. Funding should reflect that. The seasonality of working capital can then be accommodated by taking short term funding for the period when stocks and/or debtors are high. A really cautious approach would be to use all long term funding and accept having excess cash for the off-season. 3 Why does it matter how much working capital we have? The short answer is that it is an investment and we want to get the highest return for the lowest investment if our target is to increase shareholder value. Does extra working capital mean that we can sell more goods? Or charge more for our goods? There may be times when the answer to those questions is yes – and then we should encourage more investment. But much of the time the answer is no – so we should use less rather than more. We can overdo the pressure on working capital though. For example, if we cut down on stock in a retail operation then we may lose customers because we don’t have what they want to buy. If we cut down on debtors by being aggressive with late-payers then again we can lose customers. We need to find the right balance. A very useful metric for analysis and monitoring is the proportion of sales that is tied up in working capital; net working capital % sales. A percentage of sales is a relatively rough measure, but it is surprisingly stable over time as sales levels vary. As sales levels grow, more stock and debtors are needed. As sales levels decline, fewer stocks and debtors are needed. Working capital when sales grow Question 3 Which of the following would have the highest working capital ‘cost of growth’? (a) An engineering business making a wide range of steel bearings for short notice draw down by industrial customers (b) A mobile phone operator (c) An advertising agency designing advertisements and buying advertising space (d) A large food retailing business (e) Don’t know Answer The right answer is (a) an engineering business making a wide range of steel bearings for short notice draw down by industrial customers. The wide range of bearings and the short draw down means that a lot of stock has to be held. Couple that with industrial customers, who buy on credit rather than retail customers who pay cash, and the level of stock and debtors is likely to be high. But what about creditors, the offsetting item? Input costs, and therefore creditors, are likely to be steel and people cost. Debtors and stock are likely to be much higher than creditors giving a high percentage of sales tied up in working capital. Mobile phone operators have a heavy fixed investment but a relatively modest investment in working capital. This is because debtors are relatively small – either ‘pay-monthly’ or prepaid – and stock is non-existent. Creditors on the other hand – trade creditors accruals and deferred income – more than outweigh the investment in debtors. The result is a negative investment in working capital. This is the situation for the large food retailer too. Although the physical amount of stock is high, the relative amount probably averages across products at about a week’s worth of sales. Contrast that with the six weeks or so of trade credit that they take and their situation becomes clear. Add in the nature of retailing, i.e. sales are for cash not credit, and it is clear that a food retailer should have a negative investment in working capital. The advertising agency is in broadly the same position, a minimal amount of stock, but possibly high debtors. Offset that with the fact that they can take credit from the purchase of advertising space and again we have low or negative levels of working capital. The key in all of these is that as firms grow, their working capital grows at the same rate – a wellmanaged firm will maintain broadly the same proportion of its sales. A high level of working capital means that the investment needed to fund growth is high. If the level of working capital is, say 20%, then if sales grow from £100m to £110m then the working capital needed to fund that growth will be 20% of the growth, i.e. £2m extra investment. Unfortunately the extra stock and debtors has to be “paid for” before the extra profit on the new sales is received. 4 Working capital and lending risk If growth is pursued without the extra investment the most common problem is ‘overtrading’. Most commonly seen in small businesses, this is a management problem as much as a financial problem – too much to do, chasing fires all the time. Financially, stock is always short and debtors always being chased earlier than they would normally. The most serious implication of the problem is that, unless the problem is correctly diagnosed, the solutions tend to make things even worse. The problem can easily be seen as a liquidity problem – being short of cash. The solution is to get more sales to provide extra profit. Of course, more sales is the last thing needed – more sales is the problem not the solution. The other side of the coin of working capital intensity is when sales decline. Question 4 Which of the following businesses is likely to suffer the biggest cash impact when sales decline? (a) An engineering business making a wide range of steel bearings for short notice draw down by industrial customers (b) A small restaurant chain (c) A department store (d) A large food retailing business (e) Don’t know Answer The right answer is (d) a large food retailing business. The engineer will have a large working capital and so as sales decline, cash is generated as debtors pay up and we have to invest less in new debtors and stock. The restaurant chain and the department store will both probably have a very small level of working capital and so will not suffer a dramatic change in cash. The large food retailer is likely to have a negative working capital, as already described. It is decline in sales that creates the problem here. Normally we get cash from customers before we have to pay suppliers, but when sales decline we have to pay suppliers at our old level of operation while getting in cash at a reduced level. The negative working capital works against us. Growth generates cash but decline consumes cash. If lending facilities were already stretched before sales declined, then this cash consumption can be a major problem. Imagine arguing the case for more borrowing – we need to invest more in working capital because sales are declining! So what does the food retailer do? Maybe cut prices to shore up sales? In terms of immediate cash flow, that risks making things even worse, especially if the ploy doesn’t increase sales as hoped. The price cut might need to be significant, we don’t rush for a 5% discount any more. So in terms of risk for a lender, borrowing for working capital investment may be less risky for the engineer because if things go wrong and sales fall, then cash is generated from reduced working capital and the debt can be repaid. But businesses with negative working capital have exactly the opposite effect – debt for working capital here is more risky. 5 Working Capital and Liquidity When we talk about working capital changes – growth consuming cash and decline releasing cash – we assume that working capital is controlled. In practice that control is very difficult to achieve because it involves the active, successful cooperation of purchasing, selling and production departments. As sales increase it is very tempting to overdo the increases in purchasing, for example. As a purchasing manager the last thing you want to happen is to be caught out and ordering too little – you would be blamed for running out of stock. Similarly the production manager authorises more overtime or more hiring than might be strictly necessary for the same reasons. Decline is even harder in practice, reducing stocks and debtors in line with sales is notoriously difficult. A well managed company will accept some variation, but re-impose control fairly quickly. A badly managed company may not realise the problem and suddenly experience cash shortages. Question 5 What is the best measure for determining and forecasting liquidity? (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) Answer A cashier’s forecast for the next three months A cash flow forecast for the next three months A projection of current assets less current liabilities A projection of ‘current assets less stocks’ divided by current liabilities Don’t know The right answer is (b) a cash flow forecast for the next three months. Cashier’s forecasts are said to include detailed knowledge of when individual debtors actually pay. They are useful over very short periods, but for a three month period they may be less reliable because they include the settlement of debtors yet to be invoiced and purchases yet to be made. Without knowledge of sales forecasts and other inputs for a cash flow forecast, this is unlikely to be accurate. Current assets less current liabilities is a confusing measure because both working capital and the means of funding is often included. So, in theory, these are all short term assets and liabilities but the funding for stock and debtors is not always short term – in fact would ideally not be short term. A similar problem exists for ‘current assets less stock’ divided by current liabilities, often called the quick ratio or the acid test. Ratios of current assets and current liabilities can be misleading if they are taken at face value. Many textbooks suggest that an ‘acceptable’ level for the current ratio is 2. Yet many retailers have ratios much less than 1 – because they have large creditors and relatively small stock and debtors – and they are certainly not running out of cash. The nature of the business is highly significant in interpreting all ratios – these especially. Cash flow forecasts are the only real way of ensuring that cash requirements are within limits – i.e. for forecasting liquidity levels. That is why cash flow forecasting has such a high priority in many companies. Liquidity is a slippery concept because all financial problems ultimately resolve themselves into a liquidity problem. Too little profit, too much investment, too much growth; all of them eventually show up as a liquidity problem. 6 The attraction of too much working capital This may seem an odd subtitle – how can too much working capital be an attraction? Within the company that is unlikely to be true. But to an acquiror it might be very attractive. Acquirors are attracted to companies that are not well-managed. These are companies that can be bought and then transformed into something better performing. Question 6 As an acquirer, you have identified a poorly managed business that you believe you can transform. At present the investment in working capital is 22% of sales. You believe that you can reduce that dramatically to 20% in the first year of your ownership, 18% in the second year and then finally 15% in the third year. This level of 15% will then be the stable level of working capital investment for the business. What is the acquisition value of this working capital reduction if sales remain constant at £100m per annum and your cost of capital is 10%? (a) (b) (c) (d) £7.0 million £6.3 million £5.7 million £5.0 million (e) Don’t know Answer The right answer is (c) £5.7 million The gross reduction in working capital is £7m, i.e. £22m down to £15m, but it is spread over three years. The present value, i.e. the impact on the acquisition value, is Year 1 change = £22m - £20m = £2m discounted by one year at 10% = £1.8m Year 2 change = £20m - £18m = £2m discounted by 2 years = £1.65m Year 3 change = £18m - £15m = £3m discounted by 3 years = £2.25m Total = £5.7m This is a one-off gain, extracting the cash investment cannot be repeated year after year. Effectively the business has an excess investment of £7m. That can be taken out over a period of three years but it can’t be repeated.