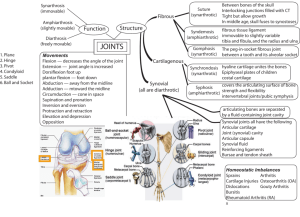

REVIEW: Hyaluronan and synovial joint: function, distribution and

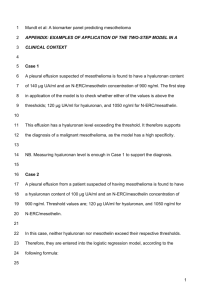

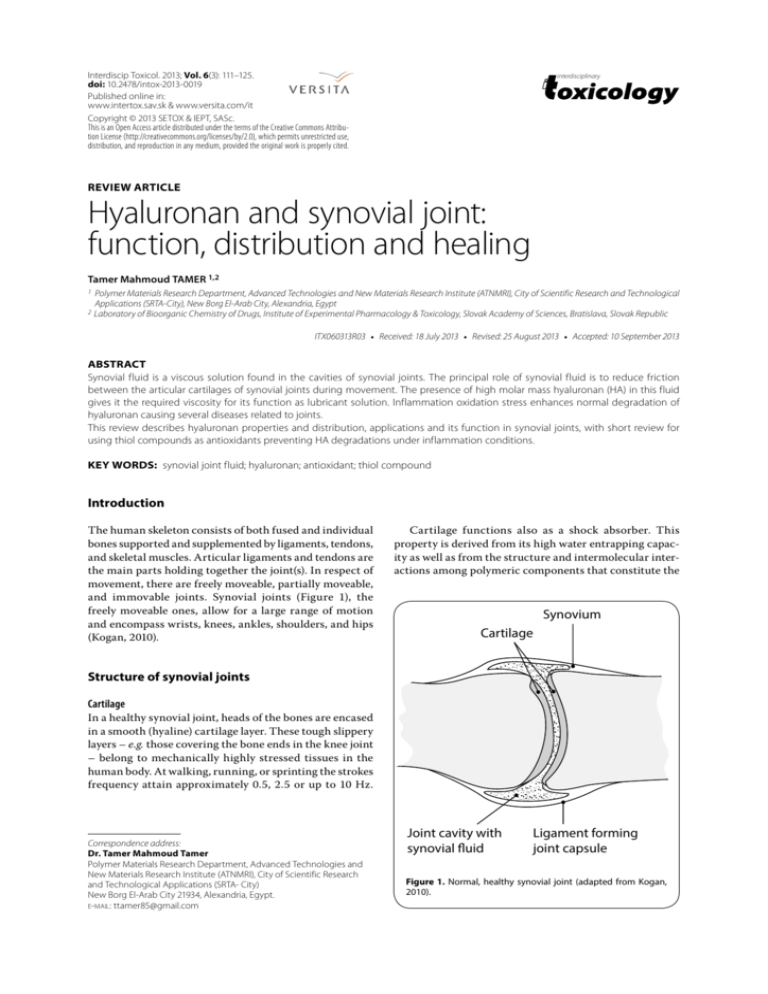

advertisement