Recovery-Remission from Substance Use Disorders

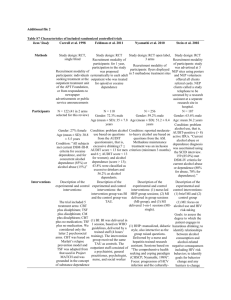

advertisement