MOVING HISTORY: THE EVOLUTION OF THE POWWOW

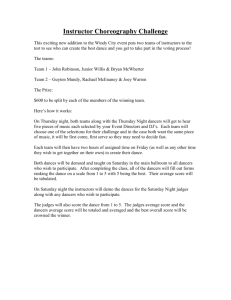

advertisement