Discussion Paper 225 - Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy

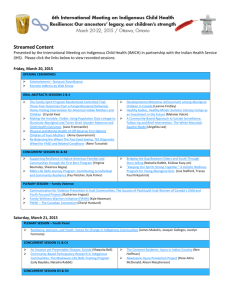

advertisement