Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention

advertisement

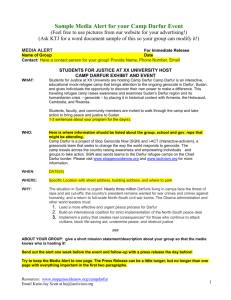

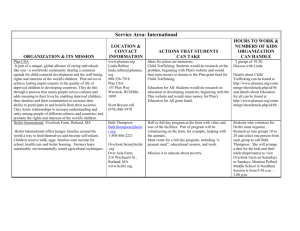

This article was downloaded by:[Hagan, John] On: 10 January 2008 Access Details: [subscription number 788405305] Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713690200 The Mean Streets of the Global Village: Crimes of Exclusion in the United States and Darfur John Hagan a; Wenona Rymond-Richmond b a Northwestern University, American Bar Foundation, Evanston, Illinois b University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts Online Publication Date: 01 January 2007 To cite this Article: Hagan, John and Rymond-Richmond, Wenona (2007) 'The Mean Streets of the Global Village: Crimes of Exclusion in the United States and Darfur', Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 8:1, 54 - 80 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/14043850701695049 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14043850701695049 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 The Mean Streets of the Global Village: Crimes of Exclusion in the United States and Darfur JOHN HAGAN1 AND WENONA RYMOND-RICHMOND2 1 2 Northwestern University, American Bar Foundation, Evanston, Illinois, USA University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA Abstract This paper considers similarities as well as differences in statebased systems of selective exclusion found in the United States and Sudan. Albeit in different ways and to different degrees, large numbers of homeless adults and children are denied the basic human right to secure shelter in the nations of both the Global North and the Global South. Homelessness and imprisonment are pervasive forms of social exclusion in the late modern Global North, while forced migration and mortality are persistent forms of social exclusion in the contemporary Global South. The domestic policies of exclusion in the North—with their legalized use of arrest, due process, conviction, incarceration and homelessness—are a world apart from the policies of criminal exclusion in the Global South—with their death squads, militias, disappearances and displacements. Yet both depend on repression rather than restoration. Mass incarceration and genocidal death and displacement display an awkward symmetry along the mean streets of the global village, and the fragile The Global North and South Should it be entirely surprising that a country, the United States, with a history of importing African slaves and genocidally killing and displacing its indigenous people, would four centuries later respond in ambivalent ways to an African country, Sudan, that has enslaved, killed and displaced its own indigenous population? Perhaps these countries are not as entirely different as they might at first seem. There may be lessons of broader relevance in the seemingly disconnected but in some ways similar and overlapping experiences of the United States and Sudan. Criminology is an important venue for the development of such lessons. 54 DOI: 10.1080/14043850701695049 and disrupted families of the North parallel the destroyed and displaced families of the South. They are parallel faces of vulnerability. The mean streets of the United States and Sudan are not the same, but their risks and vulnerabilities involve parallel and failed policies of punishment, repression, and exclusion. key words: Displacement, Darfur, Exclusion, Genocide, Homelessness, Imprisonment, Killing, Mortality, Rape, Sudan Our starting point is two jarringly different images of the consequences of Sudan’s recent genocidal history. The first image is the well told story in Megan Mylan and Jon Shenk’s documentary, The Lost Boys of Sudan, and in Dave Eggers’ novel What Is What. This is the true tale of the thousands of young boys who when confronted with terrifying choices in the early 1990s between being child soldiers, slaves, and death, chose to flee from southern Sudan to refugee camps in Ethiopia. When life proved desperate there too, many of these same youth fled back through the still raging killing fields of southern Sudan, winding up in refugee camps in Kenya. Finally, in 2000, the US governJournal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention ISSN 1404–3858 Vol 8, pp 54–80, 2007 # Taylor & Francis Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Figure 1. Lost Boys of Sudan (www.lostboysfilm.com). ment began bringing some of these youth to the United States where they received help, often from church groups, in negotiating a challenging inclusion and reintegration into more normal lives in the Global North (Cheadle and Prendergast 2007). This outcome was an enormously important accomplishment of restorative justice for the fortunate Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention few who survived their early lives as child victims and soldiers in Sudan. The second image is a less uplifting and more sobering reflection of the exclusionary stigma and punitiveness that more often has confronted refugees from Sudan’s genocidal policies. This second image appeared in a colour photo ‘above the fold’ on the front page 55 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Figure 2. One Sudanese refugee, left, crying out as he was grabbed by riot policemen, as another, right, tried to hand over his child through a bus window after both were arrested by Egyptian security troops. (New York Times December 31, 2005) Courtesy of AP Images/Ben Curtis. of the New York Times, on New Year’s eve, 2005. The picture was of a Sudanese man crying out as another man tried to deliver his infant child to safety through a bus window as they were forcibly removed by Egyptian police from a protest in Cairo. The police killed at least 23 adults and children that day, when hundreds of Sudanese refugees refused to leave a public park they had occupied to protest denials of their refugee claims by United Nations officials. The officials implausibly told thousands of Sudanese camped in the small park across from their offices that they were ineligible for relocation because it was safe to return to their ‘homes’ in Sudan. When the officers charged, women and children tried to huddle together, 56 and to hide under blankets as some men grabbed for anything—tree limbs, metal bars—struggling to fight back, witnesses said. The police hesitated, then rushed in with full force, trampling over people and dragging the Sudanese off to waiting buses… (Allam and Slackman 2005:1) Those who survived were bused away and later released on the streets of Cairo with no possessions and nowhere to go (Allam and Slackman 2005)—yet again the victims of social exclusion. No reports followed as to what became of the latter group of refugee claimants and their children, but it is reasonable to imagine that their fates on the streets of Cairo were far less favourable than those of the lost boys of Sudan who were allowed sanctuary in Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village the United States. Of course, the Global North has its own problems of social exclusion, notably including homelessness and imprisonment, and the field of criminology has copiously researched the life course outcomes of young as well as older persons who are treated with analogously punitive (e.g. arrest and imprisonment) as opposed to reintegrative policies (e.g. shelters, alternative school and work programs) in North America. We can learn much from this criminological research in the Global North, and we argue in this paper that the implications of this work are instructive for our understanding of the Global South as well as the Global North—not just because our fates are linked by the shrinking and interconnected dimensions of the joined worlds in which we live, but also because even more fundamental aspects of our geographically separate lives may be more intertwined than they ordinarily seem. In particular, we argue that there are lessons from the experiences of homeless youth and families in the Global North that can make the Global South, including the life prospects of the displaced and dispossessed in Darfur, more understandable. This paper ultimately considers similarities as well as differences in the state-based systems of selective exclusion found in the United States and Sudan. Readers may wish to jump ahead to Table I below for a summary statement of where this discussion is heading. Our discussion begins with a more broadly based comparison of policies of social exclusion in the Global North and Global South. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention The criminology of two hemispheres Albeit in different ways and to different degrees, large numbers of homeless adults and children are denied the basic human right to secure shelter in the nations of both the Global North and the Global South. For some, this form of social exclusion is a cause of involvement in crime, while for others it is a form of criminal victimization in itself. For many, it is both. Homelessness and imprisonment are pervasive institutions of social exclusion in the late modern Global North, while forced migration and mortality are persistent institutions of social exclusion in the contemporary Global South. We have already seen that the shrinking dimensions of world history and worldwide population shifts interconnect these institutional trends, often yielding conflict, as when the feardriven exclusivity of the North pushes back against the successive waves of forced displacement and pleas for sanctuary from the South. These hemispheric processes beg for comparative research and understanding, and criminological theory and research can speak to this need. Major contributions of late modern criminology speak in useful ways to the themes of social exclusion and inclusion that we explore in this paper. Any accounting is highly selective, but brief mention of some of the most notable contributions of recent recipients of the Stockholm Prize in Criminology can help to make this basic point. For example, John Braithwaite (1987, 2002) explains how stigmatic social exclusion and more inclusive and reintegrative shaming policies can characterize opposing regimes of punishment and strongly 57 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village influence the life paths of those who experience them. Alfred Blumstein (2006) explains how an exclusionary period of escalating imprisonment and confinement of young, black males linked to a perceived drug epidemic in the United States has prolonged the challenge of encouraging desistance from lifelong criminal careers. Losel and Schumucker (2005) explains how social cognitive treatment programs in community settings can reduce persistent criminality. Moffit (1993) explains how adolescent-limited involvements in antisocial behaviour followed by social reintegration and inclusion can be distinguished from life course persistence in antisocial behaviour and its exclusionary developmental consequences. This contemporary criminology builds further on the shoulders of giants. For example, when we elaborate the developmental concept of antisocial behaviour with Robert Merton’s classic sociological typology that highlights ‘innovation’ and ‘rebellion’ as forms of criminalized deviance, we have the foundations of a late modern criminology that has much to tell us about the causes and consequences of not only the street crimes of the Global North, but also about crimes against humanity and the responses they provoke in the Global South. What we have learned in the North can tell us much about the South, while the lessons of the South may also be consequential for the North, if only partly as a result of the forces of displacement and immigration already noted. We begin in the more familiar terrain of North American criminology, before returning to the urgency of current lessons from the Darfur region of 58 Sudan. We review research indicating that reintegrative and restorative justice policies providing shelter and assistance are successful in limiting life course persistence in delinquency and crime. Alternatively, comparative research reveals more punitive and stigmatic policies are more likely to produce enduring criminal careers. Yet leading late modern states in the Global North, such as the United States and Great Britain, have trended toward increasingly punitive and stigmatizing justice system policies (Garland 2001). These are policies of legalized social exclusion. We consider new evidence that the collateral intergenerational consequences of this kind of institutionalized legal exclusion of parents are to increase family disruption, homelessness, educational detainment, delinquency and crime (Foster and Hagan 2007). We argue that underwriting all of this are distinctive alternative collective framings of groups, such as the homeless and displaced, in exclusive as contrasted with inclusive terms. The difference is as distinctive as the alternative collective framings in the nations of the Global North of ‘street youth who can be helped’ and ‘street criminals who must be punished’. If trends in the Global South are especially dire, they are foreshadowed by the often downward trending experiences of the Global North. The challenge is to see the countertrends in what otherwise too often seems an accelerating downward descent. Out of this mixed story comes a rich research agenda for a changing criminology, including a better understanding of some of the most desperate criminality of the Global South. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 Street youth and street criminals in three cities Two cities in the Canadian Global North, Toronto and Vancouver, adopted contrasting inclusive and exclusive policies in relation to homeless youth in the 1980s and 90s. The result was a research opportunity for the first author of this book to consider how alternative policies of inclusion and exclusion impact on homeless youth and street crime in the late modern urban settings of the Global North (Hagan and McCarthy 1997). A further study undertaken at the turn of the millennium in Glasgow, Scotland (Fitzpatrick 2000), provides a subsequent opportunity to confirm and extend some of the findings of the Canadian research—many thousands of miles away in another part of the Global North. We begin with Toronto and Vancouver. On the one hand, Toronto had many features of an inclusive and restorative social welfare model that framed youth living on the streets and away from home in the developmental vernacular of ‘street youth’ or ‘street kids’. In Toronto, provincial legislation allowed youth who lived apart from their families and without parental consent to receive emergency and longer-term public shelter and financial assistance. Thus in the 1990s, there were four hostels in Toronto reserved exclusively for youth aged 16 through 21. Although these hostels had their problems, and some youth preferred to live on the streets, most youth clearly valued the shelter and other services provided by these youth-oriented settings. The situation in Vancouver was far different. Vancouverites worried about Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention the enticements of their city’s mild climate and unique coastal location. They foresaw security threats in an unceasing onslaught of westward migration. In the 1990s, the province and city’s welfare policies were restrictive and exclusionary. Family and welfare legislation required that youth living apart from their families in Vancouver could only receive publicly funded support in unusual circumstances. Care providers could only offer shelter to youth if they first had parental permission to be away from home—an unrealistic precondition for youth in violent conflict and often hundreds or even thousands of miles away from their parents. Beyond this, authorities in Vancouver refused to implement a framing of ‘street youth’ that was separate and apart from ‘street criminals’. Thus in the 1990s, there was no developed system of hostels, shelters, or safe houses for the short-term housing of homeless youth in Vancouver. Very few settings provided support for these youth on the street. They were stigmatized as ‘ordinary street criminals’ and socially excluded. The situation in Vancouver made the police the first responders to homeless youth. The police responded either by returning youth to their families, who were liable to criminal prosecution if they refused to accept and promise to support their children; or by placing the youth in government care and sending them to a foster or group home; or by preemptively arresting and jailing these youth. These options did not offer promising solutions to problems that caused these youth to leave their homes in the first place. 59 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Our panel survey interviews with the youth in the two cities confirmed that the settings and alternative policy models made a difference. This was reflected most clearly by a strong effect of being in Vancouver as contrasted with Toronto on involvement in crimes of theft, drugs, and prostitution. The results further highlighted another key difference in outcomes between these cities, one that further diminished involvement in street crimes in Toronto. Toronto’s inclusive social welfare model of providing access to overnight shelters and social services reduced exposures to the criminal opportunities of street crime networks and subcultures, whereas Vancouver’s exclusionary crime control model and absence of assistance made these exposures more common. Heightened exposure to the street and its criminal opportunities intensified a movement toward the fulfillment of criminalized expectations, including embeddedness of these youth within criminal networks and without legally employed peers (Hagan 1993). Vancouver youth were also more likely to be charged by the police for their involvement in street crime, which is, of course, also consistent with an exclusionary crime control model, a framing as street criminals, and inconsistent with getting and keeping jobs. More generally, the direct and indirect effects of taking to the streets in Toronto’s more inclusively and Vancouver’s more exclusively framed policy settings illustrate the significant roles that macrolevel policies play in determining life outcomes. Inclusive and exclusionary framings and their connected policies can determine life paths that lead further into or away from the 60 criminally networked subcultures of the streets that pervade cities of the Global North. Confidence in the preceding conclusion is increased by a fascinating yearlong intensive study of the lives of homeless youth across the Atlantic on the streets of Glasgow, Scotland (Fitzpatrick 2000). By the year’s end, this ethnographic field study confirmed that those youth who avoided the ‘homeless subcultures’ of city centres and stayed in youth-specific (‘street kid’) shelters were also able to take advantage of social services and achieve better employment outcomes. These latter youth who participated in the specialized programs designed to reintegrate them into work and school programs and to reframe them as conventional adolescents were better able to avoid the ‘downward spiral’ experienced by youth who remained outside this sphere in adult-dominated hostels. The latter youth spent much of their time hanging out on street corners with other homeless youth who saw themselves and were seen by others as street criminals. From North to South What can the street experiences of homeless youth in the Global North tell us about the Global South? In the Global South, late modern economic policies imported from the Global North often combine with the strengths and weaknesses of local nation states in ways that threaten family survival and intensify youth problems. Latin and South America are sites of prodigious homelessness yielding corresponding levels of family disruption and heightened risk behaviour among young people, who as Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village in the Global North are most often seen as street criminals. Also as in the Global North, the latter problems peak in late adolescence and early adulthood. Of course, some Latin and South American as well as African nations are also victims of direct forms of social exclusion, including state-led military and paramilitary regimes that organize massive ‘disappearances’ as well as fullfledged massacres, resulting in even more extensive family displacement and destruction. Sub-Saharan Africa is today the epicentre of such one-sided, state-led violence against civilians and families. The Middle East and North Africa are also sites of surges in multisided violence against civilians (Liu Institute for Global Issues 2006:Chapter 2). Rebellion against these circumstances is a predictable result, and again the demography of age and crime informs the shape and form of this rebellion. Darfur, of course, is our focus. The challenge of the remainder of this paper is to use new evidence from selected sites in Darfur to illustrate the range of consequences that assaults on the lives of African youth and their families are creating for current and future generations. There are, of course, differences of kind as well as degree between the experience of genocidal victimization in Darfur and the problems of youth in the Global North that we have thus far emphasized. Yet related life course challenges exist for high-risk youth throughout the world (Osgood et al. 2005). Our argument is that these separate but related problems of youth present an urgent new research agenda that underlines the need for a reconstituted and more internationally focused science of crime. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention To introduce as well as provoke this new research agenda, we present in Table I a comparative snapshot of similarities as well as differences in the state-based systems of selective exclusion we argue characterize the US and Sudan. We acknowledge that other countries should be included in this comparison. For example, China probably should occupy a place in this figure between the US and Sudan, while Canada and many European countries are likely to be to the left of the US. Elaborations of this figure await further research. We focus first on the US and Sudan. Racial selectivity is a pervasive feature of both the US and Sudan state-based systems of exclusion. Polarized racial images are prominent in both countries, resulting in practices of differentiation if not oppression. For example, the New York Times columnist Bob Herbert (2007) recently observed that in the United States ‘No one is paying much attention, but parts of New York City are like a police state for young men, women, and children who happen to be black or Hispanic. They are routinely stopped, searched, harassed, intimidated, humiliated, and, in many cases, arrested for no good reason’. Of course, Herbert qualified his observation by drawing ‘likeness’ and not ‘equivalence’ between the US and police states elsewhere. Selective practices characteristically are implemented indirectly in the US and directly in Darfur, which can be a crucial difference. Thus in the United States, racial differentiation is customarily legalized through recourse to juridical procedures, which may or may not 61 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 Table I. State-based systems of selective exclusion (institutionalized forms of removal and relocation) Example states: United States Exclusionary method: Selection mechanism: Institutional authority: Indirect Racial differentiation Legal/juridical procedure Operational mode: Putative rights and protections: Individualized Domestic constitutional, civil, and criminal law Forms of exclusion: Police harassment, Arrest and conviction; Incarceration; Homelessness; Disenfranchisement; Death penalty Crime as war (‘war on drugs’) Criminal innovation, recidivism, and mass incarceration (street crimes) Theoretical metaphors: Predictable consequences: prove to be discriminatory in themselves. The Sudanese state organizes racial oppression more visibly and directly in Darfur: through the unchecked command chains of the polity and military and paramilitary forces. This difference implies individualized punishment in the US and collective punishment in Darfur. However, both forms of punishment create collateral consequences (Hagan and Dinovitzer 1999) . Ideally, there should be checks on practices of racial differentiation. Of course, these due process checks and procedures depend on the enforcement of domestic constitutional, civil, and criminal law protections in the US, while 62 Sudan Direct Racial oppression Political/military and paramilitary chain of command Collectivized International humanitarian and criminal law Mass killings and rapes; Displacement; Deportation; Property loss; Refugee status War as crime (genocide) Organized attacks, armed rebellion, and counterinsurgency (war crimes) in Darfur there is (thus far) an ineffective reliance on international humanitarian and criminal law. Organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch have limited success in delivering protection in both places, but especially via the International Criminal Court in Darfur. Weaknesses in legal and other protective measures in both the US and Darfur result in extensive racial disparities. These follow in the US from discriminatory practices of police harassment, arrest, conviction, incarceration, homelessness, and disenfranchisement. The resulting racial differentiation, including wrongful convictions, leads to misapplications of the death penalty and massive Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village disproportionality in the incarceration of African Americans. Meanwhile, the racial oppression in Darfur is catastrophic. The racial consequences of the use of the political and military and paramilitary command structures of the Sudanese state to organize militia attacks on African groups in Darfur are genocidal in scale. The results are hundreds of thousands of killings and rapes, displacement, deportation, property loss, and the confinement of millions of homeless Africans in internal displacement and refugee camps. These similarities as well as differences in the US and Darfur are reflected in the parallel policy metaphors describing them respectively in terms of ‘war against crime’ and ‘war as crime’. In the US, the crime metaphor is intermittent but often explicit, and is expressed in such policies as the ‘war on drugs’, which had its modern beginning in the Goldwater US Presidential campaign of 1964 and was implemented in the Nixon Administration in the 1970s. Ironically, it is the Bush Administration which has extended the crime metaphor to Darfur with an ambivalent labelling of this armed conflict as genocide and an abstention from the UN’s referral of the Darfur case to the International Criminal Court. Our thesis is that these wars of exclusion in both the US and Darfur have enormously harmful and predictable consequences. In the US, Blumstein (2006) has explained how the massive reliance on incarceration in a ‘war on drugs’ against the crack epidemic in the 1980s resulted in the exclusionary imprisonment of older gang leaders and the creation of vacancy chains for new Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention recruits to meet continuing demands for drugs. The vacancies were filled by not only new but younger and characteristically more violence-prone recruits who set off spiralling increases in gun deaths and subsequent surges in imprisonment in the US. This produced the worst of several possibilities: an age-based and network-fed subcultural process in which mass incarceration led to more violent forms of crime through the 1980s and into the early 1990s. As we see next, an exclusionary process with some notable parallels is at work in Darfur—in this case involving state-led and -supported violent attacks on African groups that have intensified an armed rebellion that features the young male children of the targeted victims. In the same sense that mass incarceration aggravated a surge in violent youth crime in the US, in Darfur military and paramilitary attacks are intensifying an armed rebellion among newer and younger recruits. Again, this is an age-based and network-fed subcultural process in which exclusion is leading to more violence, in this case armed rebellion. If the past is predictive, this increasingly youth-driven rebellion will span war crimes in its own right. Criminology is experienced in enumerating and explaining such processes of racial differentiation and violence. Desperation and defiance in Darfur Should it be entirely surprising that in a country with a region like Darfur, where scorched earth tactics of ethnic cleansing against African groups are epidemic, would produce a violent and defiant rebel movement that is especially attractive to the youth whose families are 63 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Figure 3. Young rebel soldier in Darfur. viciously victimized? We argue that this violent subcultural response is exactly what should be predicted by a tradition of labelling and conflict theory in criminology, including, for example, Laurence Sherman’s (1993) late modern version of defiance theory. The more uplifting alternative prospect, of course, is the fate of the Lost Boys of Sudan, with whom we started this paper. Yet the true tale of the Lost Boys of Sudan is a restorative story of inclusive turning points that is even less likely for the boys of Darfur than are the parallel probabilities of ghetto youth on the urban playing fields of America becoming successful professional athletes. As we demonstrate below, age-related patterns of death and displacement are the 64 far more likely outcomes in Darfur. The lesson of defiance theory is that rebellion is too often the more plausible alternative for disadvantaged youth confronted with sobering life choices in the killing fields of nations as different as the United States and Sudan. The larger lesson of defiance theory is the unanticipated self-perpetuating rage and rebellion that is the product of repressive policies in many social settings, especially settings that provide too few peaceful pathways to success or even survival. It is in such circumstances that opportunities and strain theories classically predicted innovation and rebellion. The age-connected forms of this innovation and rebellion are foreshadowed in the criminological research already conJournal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village sidered. Again, there may be lessons of broader relevance in the seemingly disconnected but in some ways similar and overlapping experiences of the United States and Sudan, and criminology is an important venue for the development of these lessons. Our starting point is thus a third image, part myth and part reality, to consider in juxtaposition to the two we have already considered in this paper. This image is of the adolescent and young adult males in Darfur referred to in the Sudanese conflict with the demonizing imagery of ‘Tora Bora’. The Sudanese government has simultaneously identified the Tora Bora with the history of the Western frontier of the United States and the American pursuit of Osama Bin Laden (i.e. into the same named mountain range on the Afghanistan border with Pakistan). The goal of the Sudanese government is to create the image of a scourge worth fighting by brutally repressive means. The Sudanese government in press releases by its embassies and through other news media describes the Tora Bora as armed robbers and smugglers who prey on the Arab groups in Darfur, much as in the history of the settlers in the lawless American West: Historically, these groups have been existent in Darfur’s extreme rural areas for many centuries conducting acts of highway robbery. The situation here is reminiscent of the 18th and 19th century American robber… in the Wild West. The highway robbery is an ancient practice in nomadic societies which are not unique to Darfur. It is to be found in communities or similar circumstances Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention in different parts of Africa. Groups such as the Tora Bora… emerged as new fledglings conducting the old practice of highway robbery (El Talib 2004). Threatening activities of the Tora Bora are thus said to be an important source of the self-defense-motivated actions of the Arab Janjaweed militias. The argument is that ‘the major function and the raison d’être for this militia are to protect herds of nomadic tribes in western Sudan from attacks of looters, highway robbery and particularly, attacks of rival nomadic tribes at times of conflict on pastures and water’ (El Talib 2004). As noted, the Tora Bora also are linked to Islamic extremism in Sudanese government news releases. ‘Any study of the conflict in Darfur’, a government source reports, ‘can no longer ignore the clear involvement of Islamic extremists in fermenting rebellion in western Sudan’ (El Talib 2004). The evidence for this assertion, which is refuted below, again features the Tora Bora images, noting that ‘amongst the rebels there is a self-styled ‘‘Tora Bora’’ militia—named after the Afghan mountain range in which Osama Bin Laden, al-Qaeda, and the Taliban fought one of their last battles, and from which Bin Laden escaped American capture’ (AliDinar 2004). It is true that groups of young rebels sometimes also describe themselves as Tora Bora and are a small but growing part of the Darfur conflict. These youth are part of the large number of child, adolescent and young adult soldiers in Africa. Although young males may always have fought wars in the largest 65 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village numbers, they are an increasingly important and vicious part of African armed conflicts. The reasons are likely little different than in the Global North, where youth as well are valued in gangs for their loyalty, fearlessness, willingness to take risks and readily renewable availability as new recruits (Gettleman 2007). Also like gang members in the Global North, these youth often are recognizable by their adopted symbols. In Darfur and elsewhere in Africa, these menacing images include dreadlocks, wraparound sunglasses, displays of weapons and sometimes small leather pouches worn with string around their necks and containing good luck pieces. They often ride into conflict in rocketequipped pickup trucks and gun-laden land cruisers. It is important to emphasize the polarized racial identification of the Tora Bora in Darfur. There is a clear linkage between the rising racial polarization of everyday life in Darfur, represented in the reports of racial epithets heard during Janjaweed militia attacks in Darfur. We make this and related points in the remainder of this paper by drawing on a survey conducted by the US State Department with Darfur refugees in Chad in July and August of 2004 (see Hagan et al. 2005). Figure 4 presents a summary based on this survey of the rise in the explicit expression of racism in Darfur. The figure presents three-month moving averages of the reports from Darfur refugees of hearing racial epithets from spring–summer 2003 to the same period in 2004. This was a period of rise and fall in killings, which peaked at the beginning of 2004 in Darfur. 66 Figure 4 similarly shows a peak in reported racial epithets just before a widely observed peak in killing, at the end of 2003. However, this figure also shows that when attacks continued to occur in 2004, the level of reported racial epithets remained high, with about 40% of the respondents hearing these taunts, compared to about 20% at the beginning of the time series. We will see below that the Tora Bora references were nearly always accompanied by racial epithets when they were heard during the attacks. The racial and Tora Bora taunts are joined expressions of a racial demonology. In classical terms of labelling and subcultural crime theory, or Sherman’s defiance theory, the youth who take on the Tora Bora role are acting as if to say, ‘we are everything you say we are, and worse’. They have adopted what Edwin Lemert (1967) called the ‘symbolic appurtenances’ of the demonized cultural frame. The question is thus less about the existence or size of these rebel groups than about the sources and sequences of their development in settings like Darfur. There is no doubt that rebel groups such as the Tora Bora exist and pre-date the current conflict in Darfur. The most prominent of the organized rebel groups, the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), announced their existence in February and March of 2003. The SLA and JEM rebels joined forces in a seven-hour attack on the al Fasher air base with 33 land cruisers in April of 2003, destroying a number of Sudan air force bombers and gunships. The rebels killed more than 75 Sudanese soldiers and lost only 9 of their own. This attack is usually cited as the Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village 40% Racial Epithets Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 50% 30% 20% 10% 0% 4/03- 5/03- 6/03- 7/03- 8/03- 9/03- 10/03- 11/03- 12/03- 1/04- 2/04- 3/04- 4/04- 5/046/03 7/03 8/03 9/03 10/03 11/03 12/03 1/04 2/04 3/04 4/04 5/04 6/04 7/04 Date of Attack Figure 4. Moving average percentage of refugees from Darfur who reported they heard racial epithets during attacks, by date of departure (Atrocities Documentation Survey, Summer 2004). beginning of the current conflict (Flint and de Waal 2005). Yet the most exhaustive survey of reported attacks by both sides in Darfur reveals a very one-sided picture of this armed conflict, with few although increasing rebel attacks over time (Petersen and Tullin 2006). This survey is based on 178 witness statements/ accounts and reports of attacks involJournal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention ving 372 sites in Darfur from January 2001 to September 2005. Although the accounting is certainly not exhaustive, it makes use of all known available sources. It begins by revealing at least eight significant attacks on African villages before the first major rebel attack on the al Fasher air base in the spring of 2003. In total, the survey reveals only 13 attacks by rebel forces 67 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village (3% of the total). All of the remaining attacks (97%) were conducted by Janjaweed militia groups, Sudanese government forces and/or aircraft, or a combination of these groups. Perhaps of even greater interest, however, is that while 3 of the 13 rebel attacks each are reported in 2003 and 2004, the remaining 7 attacks are reported in 2005. Six of these seven attacks are reported in South Darfur, with only one in North Darfur. It is very doubtful that this reporting of attacks is comprehensive, but it may well be representative of the relative distribution and sequence of the attacks, with the rebel attacks increasing over time. This evidence is consistent with reports that the numbers of rebels seem to be growing along with the frequency of rebel actions, both against Arab targets and between rebel factions. This begs the question of who the rebels are and where they come from. Our answer is that they are usually the victims and sometimes also the perpetrators of war crimes, as well as more common crimes of subsistence. They come from all the targeted African groups—most notably the Zaghawa, Fur and Masaleit. They are mostly young, and some are under 18. All of the rebel groups—the SLA, JEM, and the newer National Movement for Reform and Development (NMRD) — are predominately made up of males in their later teens and twenties. As many as 80 Fur boys under 18 are known to have been in the ranks of the SLA and have been seen with weapons by Human Rights Watch observers (Human Rights Watch 2004a). Sudan is a ratified signatory to the Optional Protocol to 68 the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which established 18 as the minimum age for forced recruitment and calls on states to assist with the rehabilitation of child soldiers. Yet any thoughts of rehabilitation or restorative justice ignores the reality that the Sudan government’s strategy of counterinsurgency in Darfur is a policy of collective stigmatization and exclusionary punishment concentrated on the families of the African farmers and villagers who are the targets of the joined government and Janjaweed militia attacks. An important Human Rights Watch (2005) report uses the term collective punishment to aptly describe the brutality we further describe below in the southwestern part of West Darfur state: These tactics—which were replicated throughout much of Darfur—were supplemented by other particularly brutal crimes in three Wadi Saleh, Mukjar, and Shattaya localities as a form of collective punishment—and total subjugation—of the civilian population for its perceived support of the rebel movement (Human Rights Watch 2005: 11). Understanding the nature and dimensions of this collective punishment requires a further look at the pattern of victimization associated with the rebellion in Darfur. A key to understanding the consequences of collective punishment as a counterinsurgency strategy involves seeing its impact on families. The collective punishment of families in West Darfur An important way of understanding the impact of the counterinsurgency policy Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 Table II. Darfur families before and after attacks (Atrocities Documentation Survey, Chad, 2004) Settlement Percent Average family size before Average number males killed attacks of family killed Percent Average family size after reporting attacks rapes Abu Gumra Al Genina Beida Bendesi Foro Burunga Garsila Habila Kabkabiyah Karnoi Koulbous Kutum Masteri Seleya Sirba Tine Umm Bourou Near Karnoi Adar Tandubayah Near Tine Girgira Near Abu Gumra 25.66 9.29 22.62 6.75 6.68 6.81 8.63 8.63 17.88 8.39 7.51 9.59 7.79 7.23 7.13 8.66 8.56 10.06 6.59 9.33 8.44 7.76 19.94 2.43 16.31 2.19 1.44 1.44 2.15 2.18 11.68 1.23 2.44 2.33 1.37 1.13 1.13 2.69 2.44 3.88 0.65 1.87 1.06 2.12 56 87 55 92 78 96 90 95 64 94 79 76 87 89 97 77 87 76 72 86 53 91 20 45 14 38 41 38 41 33 31 0 26 47 27 29 22 27 23 35 6 0 0 12 5.71 6.86 6.31 4.56 5.24 5.38 6.48 6.45 6.21 7.15 5.07 7.22 6.43 6.10 6.00 5.96 6.13 6.18 5.94 7.47 7.38 5.64 Total 10.44 4.19 69 29 6.25 of the Sudanese government in Darfur is to reconstruct the numerical changes in family composition and how they have occurred as a result of attacks on farms and villages. We do this first by looking at all 22 settlements represented by the 932 refugees interviewed in the State Department Survey in Chad. Table II provides a before and after picture of the average families in these settlements, in terms of their mean size, loss of life and experiences of rape over the 18 months before the 2004 survey. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention This table indicates that across the 22 settlements, the average family size before the attacks included more than ten persons (10.44). By the time these families reached the refugee camps in Chad, however, they consisted of just over six persons (6.25)—having lost on average more than four family members (4.19). Nearly 70% of these lost family members were males (69.2%), while nearly 30% of the respondents (29.1%) reported that rapes occurred during the attacks. These latter numbers reflect a 69 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village pervasive pattern of killing men and raping women. The averages are influenced by especially high numbers of reported lost family members in several settlements, most notably Abu Gumra, Beida and Karnoi. For unknown reasons, these settlements which report the highest numbers of lost family members report somewhat lower rates of rape. The best documentation of the patterns of death, disappearances and destruction in Darfur is in the southwestern areas of West Darfur known as Wadi Salih and Mukjar. These are among the most fertile land areas of Darfur, and the Mukjar area includes the strategically important Sindu Hills where rebel forces have often sought refuge. Four settlements in this region are included in Table II: Bendesi, Foro Burunga, Garsila and Habila. Although the numbers of lost family members are somewhat lower in this area than elsewhere in Darfur, we will see that the overall destruction of African group life, which has led to an increase in rebel recruitment and activity, is overwhelming. This area thus provides an important illustration of genocidal victimization and its consequences in Darfur. The damage to family life in the about four settlement clusters included in Table II shows a consistent pattern. On average, the family sizes varied between six and more than eight members (6.68 to 8.63) before the attacks. Families on average lost from about one to two members (1.44 to 2.19), so that after the attacks the average family ranged in size from about four to six members (4.56 to 6.48). About 40% of the respondents from these families reported that rapes 70 occurred during the attacks on their settlements (38%–41%). Three of the four settlements reported that more than 90% of the lost family members were male, while the fourth settlement reported that 78% of those lost were male. Thus the loss of family members was pervasive, and the direct or indirect experience of rape was extensive. However, the narrative accounts we consider next make it even more clear how devastatingly comprehensive the destruction of group life was in this southwestern area of West Darfur. The destruction of Bendesi The town of Bendesi is an instructive example of genocidal victimization in the southern part of West Darfur. Except where otherwise indicated, the quoted interviews come from the US State Department survey referenced and described above (see also Hagan et al. 2005). Tensions grew between Arab herders and African farmers for at least two years before intense violence broke out in this Wadi Salih locality in August of 2003. For example, a refugee interviewed in Chad reported an early attack on the village of Kaber, south of Bendesi, in December of 2002 and several times thereafter. The attackers were Arab and dressed in khaki uniforms. An Umdha (i.e. tribal leader) and several others were killed, including several children who were thrown into a nearby river. The refugee reported that during the attack ‘they tried to defend themselves, and when they did they were defeated’. Four persons were killed and cattle were taken when Kaber was hit again in June and in the first days of August Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village 2003. A plane dropped bombs on the village in the 3 August attack. As a woman fled this attack, she ‘stopped at my father’s shop and found him dead and the shop looted. I also saw the body of my ex-husband. My cousin was shot too, and died later of the injury’. Another village, Bamboi, was bombed and strafed in early July, with the attacking Janjaweed militia calling their victims ‘Nuba [Arab for black slave] dogs’. Another respondent reports two killings on the road to Bendesi. These ‘pre-attacks’ were taken as warnings, and the populations of Bendesi and Mukjar began to swell as farmers and villagers in smaller centres began to move toward what they hoped would be the safety of larger settlements (Physicians for Human Rights 2006:24). The population of Bendesi was seven to ten thousand before widespread violence broke out in the area. The vegetation around the town is lush, and the surrounding region is a fertile growing area. In the past, Arab nomads often passed through the area and stayed with their herds near the town of Bendesi. They frequently were seen in the markets of this and surrounding towns. The town of Mukjar is located 25 kilometers to the northeast. Arab herders have long regarded land more generally in Darfur as belonging to Allah, with rights of use and settlement contingent on mutually advantageous exchange relationships (de Waal 2006). From the farming season of approximately July to February, the nomadic herders traditionally kept their livestock off the cultivated land and on established migration routes. Farmers in the Bendesi area complained that Arab Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention herders were increasingly allowing their livestock to graze on their crops during the growing season. The effects of desertification and scarcity of grazing opportunities likely fueled the growing tensions. In 2002, a dispute followed an attempt to negotiate this disagreement and resulted in the shooting of four African men. For the next two years, Arab groups were accused of looting and shooting African farmers in this area (Physicians For Human Rights 2006: 23–4). The African groups of this area—who are mainly Fur but also Masaleit and Zaghawa—began to arm and defend themselves. A resident of Bendesi remarked that negotiation with the Arab herders was futile: ‘Anyone who tried to dispute them was shot… Also during this time, it became very unsafe for young women to go outside the village… Many young women were beaten and raped and were killed if they refused’ (Physicians For Human Rights 2006:24). The local African tribes began to secretly arm and train themselves as a defense measure. An Umdha (i.e. a ranking leader in the Fur group) reported that arms became more readily available in the area following the civil war in Chad. Local Tora Bora rebels reportedly were smuggling them across the border. These rebels also attacked the local police and army barracks. In early August, the SLA attacked and stole weapons and a radio from the Bendesi police station, killing two Arab men. Similar raids occurred in Mukjar and surrounding villages (Human Rights Watch 2005:6). Tension mounted in the early weeks of August, 2003, as the government 71 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village began to actively recruit local Arabs into more formally organized militias. There was a public call for recruits, but only Arab volunteers were taken, and Africans were explicitly turned away. Ali Kushayb, an Arab militia leader charged with crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court, led this recruitment effort, integrating the militia members into the structure of the Public Defense Forces of the region. The local African groups identified these militias as Janjaweed, characterizing them as highwaymen and robbers—the mirror image of the Sudanese government’s depiction of the Tora Bora. Ahmed Harun, a middle-level Sudanese ministerial official responsible for Darfur and also charged with crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court, was seen on numerous occasions during this period in the Bendesi/Mukjar area. The Umdha interviewed in the Chad refugee camp recalled that ‘I was at a meeting where he announced that those that disrespected the government should be cleansed away by the government’. He reported that ‘the government has a propaganda program against blacks… which tries to show that all blacks are rebels and should be fought’. Harun is identified in the interviews as the government architect of the strategy of collective punishment which held all the African civilians in the Bendesi area responsible for the scattered local rebel attacks on police stations and government installations. Harun used the analogy that these farmers and villagers were the ‘water’ in which the rebel ‘fish’ swam and survived (International Criminal Court 2007). 72 As noted in the Chad State Department interviews cited above, smaller villages surrounding Bendesi were attacked in the first weeks of August, in a lead-up to the assault on Bendesi on 15 August, 2003. Reports of more planned attacks circulated in the markets and among mothers and children. For example, one woman reported that ‘I heard about that in the market, and also from children who heard it from Arab children while herding. They were saying, ‘‘We’re going to eliminate all the Nuba and just leave the trees— we’ll even eliminate the ants’’ (Physicians for Human Rights 2006:25). The major government-organized attack in the Bendesi area began on 15 August, 2003. Witnesses reported to Court investigators that the Arab militia leader, Ali Kushayb, was seen leaving Mukjar on 15 August in a vehicle with Janjaweed militia (International Criminal Court 2007:73). He was seen later the same day in Bendesi in military uniform and issuing orders to the Janjaweed. The Janjaweed arrived at the Umdha’s house and indicated they would be back later to collect ‘zakat’—an Islamic tax. A refugee in Chad from Bendesi recalled that ‘at 7 a.m., six land cruisers with mounted guns of the Sudanese military force arrived and on a loudspeaker announced that everyone had to bring their goods and be assessed for taxes in a central area’. The government troops on the land cruisers with machine guns were accompanied by Janjaweed on horses, camels and on foot. The combined force included more than 500 men. The government troops and Janjaweed simply waited an hour or Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village two while the people of Bendesi gathered with their possessions for ‘tax collection’ and then attacked. The government soldiers had land vehicles with fixed machine guns and rockets, while the Janjaweed attacked on horseback and camels. As they rode and fired into the crowd, a refugee remembered they were shouting ‘Tora Bora’ and ‘we don’t want any blacks in this area’. This woman described seeing many people killed and injured and that as she was fleeing it felt like she was ‘running on dead bodies’. This same woman saw a 12-year-old girl raped by five men in Bendesi. The girl was abducted and later returned to Mukjar where the woman saw her again, now covered in blood. She died soon after. Another refugee in Chad from a village near Bendesi counted 32 persons killed and that girls were raped, abducted, and returned days later. Although some respondents offered exact counts of persons killed and raped, others emphasized that the attacks were too chaotic and terrifying to allow such counts. A woman observed that ‘they rode into the village and were screaming ‘‘exterminate the Fur, kill the Fur!’’. It was total destruction. I saw people dead. I saw them raping women. But I didn’t have time to count how many were killed or raped’ (Physicians for Human Rights 2006:25). A sheik said he and other sheiks were arrested and accused of being Tora Bora. He described being taken to a military base and tortured. ‘The conditions were terrible—37 men in a small room about four by three metres. We were all lying down, tied up, some on top of each other.’ He was detained for Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention seven days and heard later that three of the men died as a result of the torture. During the attack on his village, a mile from Bendesi, he heard Janjaweed shouting ‘kill the Nubas’ and that ‘the young Fur and Masaleit should be eradicated’. Many fled from the area of Bendesi to Mukjar, but to little avail. For example, a refugee in Chad said ‘we stayed in Mukjar… but it was very dangerous for men. I didn’t leave the house because the soldiers were arresting and killing many men suspected of being rebels’. Respondents consistently recalled hearing a mixture of racial epithets along with the allegations of being Tora Bora. A refugee who tried to flee but was caught in Bendesi described the Janjaweed saying to him ‘you were at Tora Bora’, which meant to him that he was from the rebel group. His captors wanted information about the sheik and information about rebels. Another respondent from a nearby village said he was told he was ‘protective of the Tora Bora’. The attack on Bendesi that began on 15 August, continued for five days, and followed a pattern that was repeated in many parts of Darfur. After the initial assault, members of the armed forces and Janjaweed went through Bendesi in a door-by-door fashion, searching for remaining residents and killing those they found. Then, over the following days, witnesses described seeing ‘the attackers divide into three groups: one burned the village; one collected animals and broke into houses; and the third chased the people who were running away… Witness DFR-023 stated that she heard the attackers say that they had been sent ‘‘to kill every black thing 73 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village except the Laloba and Daylabe trees which are also black’’ (International Criminal Court 2007:74). During this period, and over much of the next month, rapes and killings continued. A refugee in Chad was able to identify over 50 young men who were shot and killed between 15 August and 8 September in the Bendesi area. All together, he knew of 229 men who were killed. Young men were repeatedly arrested and taken into custody, where they were often tortured. Ali Kushayb was prominently involved in the operation of police stations and military bases for these purposes. A refugee in Chad also reported more than 30 girls were abducted and raped by the Janjaweed in the Bendesi area. ‘Of these, two had their throats slit, one was strangled, and one was shot when they resisted being raped.’ He indicated that Government of Sudan soldiers then took some of the women to Khartoum as a form of ‘booty’ and that the Governor and Deputy Governor of Mukjar were present during the attacks. The account of the rapes and the removal of women to Khartoum is widely enough known that the al Bashir government, in a rare intervention, authorized a court inquiry into the abduction of women and girls from the villages of Wadi Saleh in 2005 (Winter 2007). Death, survival, and rebellion The killing, abductions and the enslavement of children has long been a part of the conflict in southern Sudan, as noted in the account of the Lost Boys of Sudan above. Abductions are a smaller but still very significant part of the Darfur 74 conflict in western Sudan. To get a measure of the magnitude of the direct impact of these crimes on young males and females in Darfur, we developed a data file from the State Department survey with the age and gender of every nuclear family member identified as killed or missing in the Chad refugee sample. We then constructed the population pyramids presented in Figure 5. This figure makes it clear that two groups are most likely to be dead and missing from the families of refugee families: the ‘fighting-age’ population of African males between 15 and 29 years of age, and younger pubescent females between 5 and 14 years of age. About a third of the former young adult males as well as the latter preadolescent girls are dead or missing. This is consistent with a policy of killing the fighting-age males while raping and killing younger females. This is also consistent with an exclusionary policy that is likely to intensify rebellion among victimized groups. Note that the policy of killing fighting-age males parallels in demographic terms the earlier pattern we observed of incarcerating the young adult leaders of drug gangs in the United States. The effect of both is to create a vacancy chain for the recruitment of remaining younger replacements. The potential pool of recruits is identified in the population pyramids presented in Figure 6 from three internal displacement camps in West Darfur. This figure displays what demographers call a ‘population bulge’ of adolescent males. The German demographer Gunnar Heinsohn (2003) indicates 68 of the most populous nations of the world have Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Figure 5. Age and sex distribution of killed and missing household members (Atrocities Documentation Survey, Darfur 2004). adolescent bulges that will mature into ‘fighting-age’ bulges, and that 62 of these 68 nations are—or recently have been— characterized by high levels of violent mortality. As a result of its high birthrate, Sudan is already among these nations. In Darfur, this pattern is intensified by the killing of fighting-age males. Criminologists, among all others, are perhaps most sensitive to the violent potential of these population dynamics. In the Global North as well as the Figure 6. Age and sex distribution of surviving household members. Reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 364 No. 9442, E. Depoortere et al., Violence and Mortality in West Darfur, Sudan (2003–04): Epidemiological Evidence from Four Survey, p. 1315–1320, Copyright (2004), with permission from Elsevier. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention 75 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Global South, it is the young who are most violent and aggressive. However, they are also sensitive to further aggravating factors we have been describing, most notably, of course, the killing of parents and siblings, and the raping of pubescent girls of approximately the same ages as the surviving males. These factors combine to make an intensified rebellion predictable, with age-graded networks of recruitment and subcultural resentments playing leading roles in focusing the group-based defiance. The International Criminal Court (2007:76) also makes clear that the raping and killing reflected in these figures was explicitly linked to issues of rebels and the demonization of the Tora Bora. This point is illustrated by the following witness report described in the Court Brief: DFR-023… witnessed a separate incident of rape in which Militia/ Janjaweed and members of the Armed Forces selected and led away at least ten females between 15 and 18 years of age. She watched as the girls were raped in a field nearby… While carrying out the rapes, the attackers were saying ‘we have taken Tora Bora’s wives, praise be to God’. At least one woman who was raped bled in the course of the assault. When this happened the rapists shot their guns into the air and announced ‘I have found a virgin woman’ (International Criminal Court 2007). Despite the references to Tora Bora, the Court (78) explicitly indicates that ‘no defense was mounted by the residents, and there was no rebel presence in the town when it was attacked’. The 76 patterns we have described predict intensification of a more organized and youth-fueled rebellion. Some residents of Bendesi and Mukjar and other settlements stayed in the general area in the following months, hoping that they could salvage some of their crops and survive this period of violent collective punishment. Kushayb and Harun were seen frequently with their troops in the area. In the fall of 2003, the Arab nomadic groups brought huge herds of their camels and other livestock into the area to graze on the newly available farmlands. This further undermined the African groups’ hopes to resettle and reclaim these lands. Ali Kushayb also undertook a program to systematically eliminate the leadership of the African groups in the fall of 2003 and winter of 2004. The ‘educated persons’ and Umdhas and Sheiks of these groups were taken into custody and executed. A refugee in Chad explained that ‘they were told they were being taken to Garsila but we found them in a wadi about one half hour between Mukjar and Garsila. The bodies were in long lines of 20 to 50…. They had been shot—in the head, back, and waist’. The limited number of SLA rebel forces in the area had by this time withdrawn into the nearby Sindu Hills. In February of 2004, the SLA were able to mount some successful attacks on government troops and installations. The government struck back with an unprecedented show of force: The SLA’s presence and attacks prompted a massive response by Sudanese government forces and militias that targeted civilians and civilian Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village villages. By mid-March, the government’s scorched earth campaign of ground and air attacks around the Sindu Hills had removed almost all existing or perceived support base for the rebellion by forcibly displacing, looting, and burning almost every Fur village near the hills and then extending ‘mopping up operations’ to villages and towns farther away (Human Rights Watch 2005:11). At this point, the villages had been destroyed, and the African groups who had lived there were gone—either as a result of being killed or displaced, in large part to the refugee camps in Chad. Before and after the government offensives We have already presented evidence that in Bendesi and the surrounding area families lost on average one to two members. We have also seen that these losses disproportionately involved young adult men and teenage girls. This loss of life occurred in an intensely racial atmosphere that included both the shouting of racial epithets during the attacks and claims about membership and support of the Tora Bora or rebels in the area. A study of the Bendesi and surrounding area by ITERSOS (2005), for the United Humanitarian High Commissioner for Refugees, provides some final insights on the impact on families of the attacks. Of the total number of 245 villages and towns considered in this research, about 100 were found to have been destroyed, with 8 more abandoned but not destroyed. Furthermore, in most of the destroyed or abandoned villages, nomad Arab groups had moved on to the sites and started to put the land to use for farming or grazing. This was Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention especially true in the Mukjar area (de Montesquiou 2007). The families and children displaced by the government offensives tend to be living in highly problematic conditions. Less than 20% of the children who have survived their ordeal are attending school. Girls are even less likely to be doing so than boys. It is estimated that about 10% of the families are very conservatively classifiable as ‘vulnerable’ in the whole population of this region. This figure is estimated at 25%–30% among the internally displaced. Single parenthood is the most common vulnerability, with the greater number of these families headed by a female caring alone for her children. A social norm known as ‘zaka’ fostered the reintegration of vulnerable children and families before the recent conflict in Darfur. This norm has lost much of its force and protective capacity in the current circumstances. These are among the many and most disturbing collateral consequences of the exclusionary armed conflict in Darfur. The streets of the global village Is it surprising that there are similarities as well as differences in the patterns of legal and criminal exclusion we see in the streets of the Global North and South? As distant and foreign as the streets of Bendesi in West Darfur may seem, they bear similarities and connections to the everyday world of the Global North. In revealing ways, they are as close as the contrasting images of The Lost Boys of Sudan and the defiant rebels of Tora Bora. It is not a coincidence that the faces of the rebel youth hiding out in the Sindu Hills nearby Bendesi—with their dreadlocks, 77 Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village wraparound sunglasses, and their menacing weapons—look very much like the indigenous and immigrant youth increasingly seen on the streets of the Global North. In the high-speed warp of late modern electronic technology, the mean streets of the global village overlap more closely than we often imagine. The challenge of joining late modern domestic and foreign policies is to see common themes as well as differences. The domestic policies of exclusion in the Global North—with their legal forms of arrest, due process, conviction, and incarceration—are a world apart from the policies of criminal exclusion in the Global South—with their criminal forms of death squads, militias, disappearances, and displacements. The individualized punishments of the North offer some protection against the collective punishments of the South. One important hope is that the institutions of international criminal law can narrow the distance between these worlds. Yet both are based on punishment rather than restoration. They have notable features in common: the impulses to exclude and repress. The alternative impulses, to include and support, are elusive notwithstanding the contrasting faces of the abundance the Global North and the scarcity of the Global South. Mass incarceration and genocidal death and displacement display an awkward symmetry along the mean streets of the global village. The fragile and disrupted families of the North parallel the destroyed and displaced families of the South. They are parallel faces of vulnerability. The mean streets of Vancouver and Bendesi are not the same, but their risks and vulnerabilities are joined by parallel and failed policies of punishment and exclusion. Their fates are joined by the shrinking distances between them. The hopeful faces of The Lost Boys of Sudan are reassuring but misleading alternatives to the defiant faces of the rebel youth of Tora Bora. References Braithwaite J (2002). Restorative Justice and Responsive Regulation. New York: Oxford University Press. Cheadle D, Prendergast J (2007). Not on Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond. New York: Hyperion. de Montesquiou A (2007). Darfur Graves Unearth Evidence of Atrocities. The Moscow Times, May 28, 2007: issue 3685. de Waal A (2006). Who Are the Darfurians? Arab and African Identities, Violence and External Engagement. Contemporary Conflicts, Social Science Research Council. New York. El Talib H (2004). Definition and Historical Background of the Janjaweed. Sudan Ali-Dinar A (2004). Darfur: The Next Afghanistan? London: Darfur Information, The European-Sudanese Public Affairs Council. Allam A, Slackman M (2005). Egypt Disperses Migrants’ Camp: 23 Sudanese Die. New York Times December 31, 2005: 1. Blumstein A (2006). The Crime Drop in America: An Exploration of Some Recent Crime Trends. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention 7(Suppl 1): 17–35. Braithwaite J (1987). Crime, Shame and Reintegration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 78 Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Embassy in South Africa, August 21, 2004. Fitzpatrick S (2000). Young Homeless People. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Flint J, de Waal A (2005). Darfur: A Short History of a Long War. London: Zed Books. Foster H, Hagan J (2007). Incarceration and Intergenerational Exclusion. Social Problems 54(4): 399–433. Gamson W (1995). Hiroshima, the Holocaust, and the Politics of Exclusion. American Sociological Review 60:1–20. Garland D (2001). The Culture of Control. New York: Oxford University Press. Gettleman J (2007). The Perfect Weapon for the Meanest Wars. New York Times, April 29, 2007, section 4, P. Hagan J (1993). The Social Embeddedness of Crime and Unemployment. Criminology 31:465–91. Hagan J, Dinovitzer R (1999). Children of the Prison Generation: Collateral Consequences of Imprisonment for Children and Communities. Crime and Justice 26:121–62. Hagan J, McCarthy B (1997). Mean Streets: Youth Crime and Homelessness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hagan J, Rymond-Richmond W, Parker P (2005). The Criminology of Genocide: The Death and Rape of Darfur. Criminology 43:525–62. Heinsohn G (2003). Söhne und Weltmacht. [Sons and World Power]. Zurich: Orell Fuessli Verlag. Herbert B (2007). Arrested While Grieving. The New York Times, May 26, 2007. Human Rights Watch (2004). Darfur Destroyed: Ethnic Cleansing by Government and Militia Forces in Western Sudan. New York: Human Rights Watch. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention Human Rights Watch (2005). Targeting the Fur: Mass Killings in Darfur. A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper, January 21, 2005, New York. International Criminal Court (2007). Situation in Darfur, The Sudan. 27 February 2007. ITERSOS (2005). Return-Oriented Profiling in the Southern Part of West Darfur and Corresponding Chadian Border Area. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, July, 2005. Lemert E (1967). Human Deviance, Social Problems and Social Control. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. Liu Institute for Global Issues (2006). Human Security Brief 2006. Human Security Centre, Liu Institute for Global Issues, Vancouver, Canada: The University of British Columbia. Losel F, Schumucker M (2005). The Effectiveness of Treatment of Sex Offenders: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology 1:117–46. Moffit T (1993). Adolescence-Limited and Life Course Persistent Anti-Social Behavior: A Developmental Taxonomy. Psychological Review 100:674–701. Osgood W, Foster EM, Flanagan C, Ruth G (2005). On Your Own Without a Net: The Transition to Adulthood for Vulnerable Populations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Petersen A, Tullin L-L (2006). The Scorched Earth of Darfur: Patterns in Death and Destruction Reported by the People of Darfur, January 2001–September 2005. Copenhagen: Bloodhound. Physicians For Human Rights (2006). Darfur: Assault on Survival. Cambridge: Massachusetts. Sherman L (1993). Defiance, Deterrence, and Irrelevance: A Theory of the Criminal Sanction. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 30:445–73. 79 hagan and richmond: the mean streets of the global village Downloaded By: [Hagan, John] At: 16:00 10 January 2008 Winter J (2007). Probe of Darfur ‘Slavery’ Starts. BBC News, March 21, 2007. professor john hagan Northwestern University American Bar Foundation Department of Sociology 1810 Chicago Avenue Evanston Illinois 60201 USA Tel: +1-847 491-5688 Fax: +1-847 491-9907 Email: j-hagan@northwestern.edu 80 Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention