A Vision for the Future of the Athletic Training

advertisement

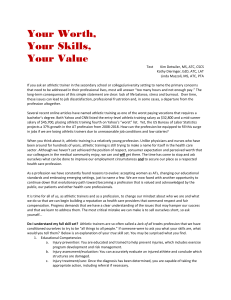

from the editor A Vision for the Future of the Athletic Training Profession The historic development of the athletic training profession is very different from that of any other health profession, having originated outside the clinical medical system when scholastic and professional sports organizations were formed over a century ago. Creation of the National Athletic Trainers’ Association in 1950 led to the development of standards for professionalism and education of athletic trainers, but the extent to which the profession was viewed as a legitimate component of the medical community was dramatically increased by the American Medical Association designation of athletic training as an “allied health” profession in 1990. Although national board certification, state regulation, and educational program accreditation standards have established a very high degree of professional competence to deliver health-related services to the physically active population, the identity of our profession remains strongly linked to the image of a minimally qualified technician who supplies water and tapes ankles for a sports team. Even though an increasing number of athletic trainers are working in physician practices, rehabilitation clinics, hospitals, worksite occupational health programs, and other healthcare organizations, many athletic trainers are extremely frustrated by a public perception of the profession that seems to undervalue the benefits that we can deliver to physically active people in settings other than scholastic and professional sports programs. A factor that has probably been a primary obstacle to the integration of athletic trainers within the mainstream clinical healthcare system is differing paradigms of care delivery. Clinical medicine has historically addressed health in the context of diagnosis and treatment of disease or injury, and procedures for third-party reimbursement of charges for medical services have reinforced a process-oriented approach to restoration of health that requires documentation Athletic Therapy Today of patient need and specified provider credentials. Conversely, athletic trainers have historically addressed health in the context of an individual’s functional capabilities with primary concern for the outcome of treatment and relatively little concern for economic factors associated with the delivery of care. Emphasis on the interrelated areas of injury prevention and performance enhancement for a defined group of individuals represents an additional distinction that is more closely aligned with a “population health” perspective. The term “population health” has historically been associated with the public health field, which is concerned with threats to the overall health of a population.1 A population may be as small as a few individuals or as large as the total number of inhabitants of several continents. The public health field includes epidemiology, behavioral health, environmental health, and occupational health. Increasingly, the term “population health” is associated with the changing reality in the organization, delivery, and financing of healthrelated services, with the population defined in terms of health plan membership, a group of employees, or the patients treated by a particular clinician, physician practice, or a healthcare delivery system. Although clinical care is delivered to individual patients one at a time, proponents of population-based health care argue that providers should systematically collect and analyze clinical data on all similar cases to improve the quality of care delivered to individual patients, an approach that is referred to as clinical epidemiology. Having recognized the growing importance of the population health concept to clinical practice, the Association of American Medical Colleges has stated, “A population health perspective encompasses the ability to assess the health needs of a specific population; implement and evaluate interventions to improve the health of that population; and provide care for individual november 2007 patients in the context of the culture, health status, and health needs of the populations of which that patient is a member.”2 The term “population health management” has been defined as the optimization of clinical, financial, and quality-of-life outcomes accomplished by management of the entire range of health risk for a population.3 The historic professional role of the athletic trainer has clearly reflected the basic principles of population health management. The primary population has historically been competitive scholastic and professional athletes, whose primary health concerns have related to musculoskeletal disorders. Although other medical conditions are less commonly encountered, athletic trainers receive an exceedingly broad education that ensures competence in managing a wide variety of neurological, cardiovascular, respiratory, digestive, and dermatological conditions associated with physical activity. Increasingly, athletic trainers are managing the health of physically active populations that are not limited to young competitive athletes, such as industrial workers, military personnel, public safety personnel, entertainment groups, and patients of a healthcare delivery organization. The susceptibility of middle-aged populations to development of chronic diseases, and the clear inverse association between physical activity and chronic disease prevalence, presents the athletic training profession with the opportunity to make a valuable contribution to the growing national crisis related to obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and rising healthcare costs. A population athletic trainers have often treated on an informal basis is the faculty and staff of the educational institution that sponsors an intercollegiate athletic program. Because musculoskeletal disorders often present a substantial obstacle to participation in regular physical activity, athletic trainers can provide an exceedingly valuable service to the institution through involvement in a formal population health management program for faculty and staff. In conjunction with physicians and other health professionals who are affiliated with the institution, provision of a screening program for “metabolic syndrome” can identify employees who need to become more physically active to prevent subsequent development of diabetes and coronary heart disease. Because optimized musculoskeletal function plays a central role in resolving metabolic abnormalities related to insulin resistance, athletic trainers should recognize the profound impact november 2007 that they can have on an individual’s future by facilitating an increase in physical activity. In addition to the improved quality of life realized by individuals, the athletic trainer is providing the institution with the tangible economic benefits of healthcare cost containment and improved employee productivity. Many corporations have recognized the value of athletic trainers for delivery of population health management services at the worksite, but educational institutions have largely failed to take advantage of the athletic training personnel and facilities that already exist. Pharmacists recognized a need to reformulate the vision for their profession, which led to a shift from an orientation primarily toward the dispensing of drugs to a greater focus on pharmaceutical care.4 The American Pharmaceutical Association now promotes an approach to practice designed to promote health, prevent disease, and assess, monitor, initiate, and modify medication use to ensure that drug therapy regimens are safe and effective.5 In the same manner that pharmacists have been changing their image from pill counters to health facilitators, the athletic training profession needs to embrace an initiative to change our image as ankle tapers to population health managers. Such an approach would not logically be interpreted as an effort to displace any other health professionals (e.g., nurses, physical therapists, exercise physiologists), because no other health profession combines expertise relating to injury prevention, physical performance enhancement, early recognition of conditions, administration of therapeutic procedures, coordination of medical care, and return to high-level physical function with a population-based approach. Rather than classifying athletic trainers on the basis of practice setting, this paradigm emphasizes the characteristics of the population whose health is managed by an athletic trainer (e.g., intercollegiate athletes, industrial workers, patients of a medical practice). As health care costs continue to increase annually at two to three times the rate of inflation, changes in the structure of the current system for delivery and finance of health care services are inevitable. To capitalize on the opportunities that develop, we must provide athletic training students with clinical experiences that address the needs of populations other than intercollegiate athletes only (e.g., university faculty and staff). Rather than limiting ourselves to populations that are already physically active, we must embrace a professional role that also responds to the needs of Athletic Therapy Today individuals who would benefit from greater physical activity but experience musculoskeletal disorders that present obstacles to attainment of an optimal level of physical activity. Furthermore, we must take steps to ensure that all athletic trainers, not just researchers, acquire knowledge in the area of clinical epidemiology and evidence-based medicine. We can continue to cling to our primary identity as a profession as it currently exists and accept the limitations that it imposes, or we can embrace a collective professional image that more accurately represents our expertise and offers solutions to the health-related needs of many populations. Gary B. Wilkerson, EdD, ATC University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Editor, Athletic Therapy Today Athletic Therapy Today 1.Tufts Managed Care Institute. Population-based health care: definitions and applications. November 2000. Available at: http://www. tmci.org/downloads/topic11_00.PDF. Accessed August 12, 2007. 2.Association of American Medical Colleges, Medical Informatics Panel, and the Population Health Perspective Panel. Contemporary issues in medical informatics and population health: report II of the Medical School Objectives Project. Acad Med. 1999;74:130-141. 3.Peterson KW. Population-based health management—Focus on the worksite. In: Hyner GC, Peterson KW, Travis JW, Dewey JE, Foerster JJ, Framer EM, eds. Handbook of Health Assessment Tools. The Society of Prospective Medicine and The Institute for Health and Productivity Management; 1999:145-154. 4.Greiner AC, Knebel E, eds. Institute of Medicine. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 2003;79. 5.American Pharmaceutical Association. Principles of Practice for Pharmaceutical Care. Available at: http://www.aphanet.org/AM/ Template.cfm?Section=Search&template=/CM/HTMLDisplay. cfm&ContentID=2906. Accessed August 12, 2007. november 2007