"Robin Hook": The Developmental Effects of Somali Piracy

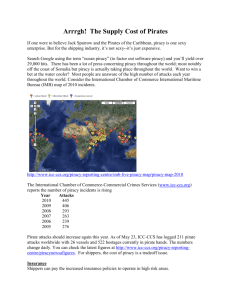

advertisement