Notes for merge with Fowzia.doc

advertisement

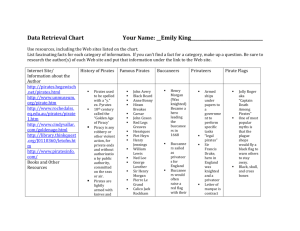

Contents: 1. Conflict timeline. 2. Slide outlines. 3. Explanatory notes and guide to selected slides 4. Bibliography [Slide 5]- What is the Relevance to us? -Somalia one of 35 currently failing states. -Comparatively small population of 9 million. -Largely anonymous post 1993 'Blackhawk Down'; potentially overshadowed by other conflicts, even within the 'bad neighborhood'. [Slide 6]- Maritime Geography -Indicates traffic density on major maritime routes. -Heaviest traffic indicated by concentration of red lines. [Slide 7]- Regional Maritime Trade -TEU is a 'twenty foot equivalent unit'; often referred to as a container. Primary method of shipping dry, non bulk cargo. - Figure of 3.2 million barrels per day does not include accurate figures for SUMED pipeline, for which figures are not in the public domain. [Slide 8]- Routes -Slide shows the increase in route distance entailed by the denial of the Gulf of Aden/Red Sea/Suez route. - Ports selected are representative of their regions; additional mileage effects are broadly same for all regional ports. - Table does not demonstrate the effect on South American trade as Suez does not provide the shortest route for these cargoes. - Effect of mileage increases exacerbated by 'transhipment'- many cargoes are offloaded at intermediary ports in order to complete other legs of their journey (ie: no direct route between small ports). As such, non viability of established Suez routes places pressure on little used facilities- lack of capacity. [Slide 9] – Economic Consequences -Previous closure occurred post 6 day War in 1967. - Feyrer's data based upon analysis of IMF Direction of Trade Data; countries placed into bilateral pairs- total of 4 observations per pair (2xImports, 2xExports) - Observed shortcoming in data is that observations are missing for many ports; therefore data scrutinised only 1294 pairs of a possible 2605. -Given increasingly global nature of trade then effects of a route closure in the current climate are likely to be far more significant then in the past. [Slide 10]- Ungoverned space -International maritime law does not create any obligation to secure territorial waters. - Out to 12NM from the low tide mark, national law takes precedence. -From 12NM to 24NM is 'contiguous zone' where state may enforce infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations. -Out to 200NM is exclusive economic zone. -In those instances where straits narrow to less than 24 NM, then a median line is drawn. [Slide 11]- Legality -Merchant vessels may be flagged (registered) in one state, owned by a corporation in another state, have cargo belonging to an entity of a third state and a crew drawn from a variety of nations. Issue of jurisdicton difficult in maritime cases. -Recent practice has been to 'catch and release' pirates. Does this lack of consequence reinforce the notion that the poor have a comparative advantage in violence/piracy? [Slide 15] – Regional Actors - Visible & invisible actors: pirates, enabling officials, financial sponsors - Changing motivations of pirates [Slide 16] – International Actors - Organizations to deter/prevent piracy - International naval forces - Maritime insurers - Private security companies [Slide 17] – Pirate Value Chain - Supply chain analysis of how actors are linked to one another - Pirate level & International level [Slide 18] – Different Perceptions - Sympathetic to pirates - Pirates as criminals - Linking pirates with terrorism [Slide 19] – The Economy of Piracy - Ransom amounts have increased despite the decrease in successful hijackings (27% in 2010 to 13% in 2011) - Average ransom: $5 million - Total ransoms collected in 2011: $159.62 million [Slide 20] - Ransom is typically paid in cash (American dollars) and airdropped onto the ship [Slide 21] – Pirate Network - Ransom pays for the direct costs of the operation, including but not limited to: - paying employees – accountant, negotiator, cook, logistics coordinator - provisions for pirates and crew (including food, drinks, qaad, clothing) - other equipment used for hijacking - Profit is then divided between - investors, 30-40% - guard force, up to 30% - pirates, 40% community, 10% [Slide 22] – Cost of Piracy - The cost of piracy includes military responses, and the direct and indirect costs for shipping companies - Indirect costs – loss of use of ship for number of days it is held ransom - Direct costs – ransom, defense mechanisms, insurance - Increased costs are reflected in prices of transported goods [Slide 23] – Economic Impact on Somali Communities - Claims that piracy positively impacts communities in Somalia - Possible benefits include: - Increase demand for local suppliers, local shops rely on pirate business - Hire people locally (crews for hijacking, local militia who guard ships, local cooks, producers, traders etc.) - Reinvest profit in community - evidence is unclear, but based on increase in houses, roads, mosques, hotels in places like Garowe (in the heart of pirates’ clan homeland) - Community can invest and buy shares through pirate stock exchanges - for example, one woman contributed a grenade she received from her husband, and went on to receive $75 000 38 days later [Slide 24] - Others argue pirates have brought harm into communities - Religious reasons - introduce un-Islamic activities (drugs, alcohol, stealing) - Economic reasons - possible Dutch disease ransom profit spend abroad [slide 25] Duffield: Insured/uninsured populations: In the case of Somali piracy, the line between insured and uninsured is not so clear. Though it is evident that the Somali pirates constitute the ‘uninsured’ sector of the world population, the ‘insured’ populations’ insurance goes directly to them, effectively insuring their livelihoods. As Murphy points out, the pirates’ “aim is to exploit the difference between marginal value placed on human life in Somalia and its value in the outside world”(Murphy: 2009) Containment: The security of the South is only important in so far as it affects Western security.This explains the international approach to Somali piracy: the aim is to contain, not to solve the problem. Greed vs. Grievance: Briefly, Collier and Hoeffler’s thesis applied to the Somali case has led us to the conclusion that this was first a grievance (about fishing and waste) and then turned into greed based violence. Rational choice theory does not apply wholly to this case either as during the Islamic government (6 months) piracy did not occur. Economic incentives do not always explain violent or non-violent behaviour [slide 26]-Tilly War- making and State-making “Early in the state-making process, many parties shared the right to use violence” (1985: 173). When the right to use violence was monopolised by one group, the people within were protected both internally (from each other) and from outside enemies. Eventually these monopolies became larger and larger and formed the state. Applying this to the Somali case, it could be argued that the pirates are in fact Tilly’s racketeers and will eventually monopolise the force and form the coming, stable Somali state. As things stand, this is a very speculative interpretation. [slide 27] -Olson Roving or Stationary bandits? Roving because they operate out of their home-base? And attack different targets every time? Or stationary because they always operate in the same waters, from the same communities on land? What if Olson’s theory was turned around: The victims are the roving ones, but so are the Somali pirates. [slide 28]-Samatar et al. The moral economy: “the poor in general have a set of expectations that govern their sense of justice. When such values are violated they respond vigorously to protect their livelihood and their sense of fairness” (1388). This ties in directly with the rational choice theory, as it demonstrates the importance that wealth and economic security have to do with livelihoods. Their categorizations of piracy provide a novel and more nuanced interpretation of the complexities of Somali piracy. Until now, the international community has not taken the various incentives for piracy into account. Because of this there has been rising resentment in Somalia (in both pirate and non-pirate communities) against the international community. [Slide 29] – Review of thesis [Slide 30] – What makes the Gulf of Aden vulnerable to piracy? - Geographical location - Historical conflict - Its proximity to wealth - Who are the threatened/threateners? - What keeps this area vulnerable?