fof-Road to revolution

advertisement

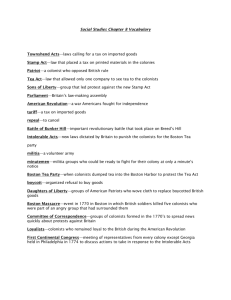

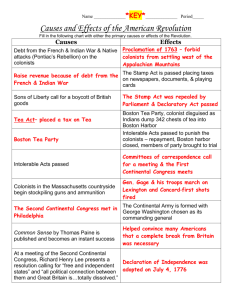

R E V O L U T I O N A N D T H E N E W N AT I O N ( 17 5 4 – 1 8 2 0 s ) The Road to Revolution: A Timeline Timeline 1733 The Molasses Act passes, imposing a duty on imports of foreign molasses. Poor enforcement leads to widespread smuggling of goods along the colonial coast. 1764 The Sugar Act passes, imposing tighter controls on the gathering of taxes on imported sugar, molasses, and rum. Students at Yale College vow to buy no more imported liquor. 1765 In an effort to raise revenue to pay for debt incurred during the French and Indian War, Britain imposes the Stamp Act, which directly taxes the citizenry. All paper documents are to carry a special stamp before use or transfer. Items such as playing cards, newspapers, licenses, almanacs, and even dice are to be taxed. Demand for repeal is immediate and widespread under the rallying cry “No taxation without representation.” In a show of growing unity and formal protest, nine of the colonies send representatives to the Stamp Act Congress, where the repeal of the Stamp Act, the right to trial jury by peers, and the desire for representation are discussed. Patrick Henry drafts the Virginia Resolves, stating that only officials elected by colonists should have the right to tax Virginia’s citizens. The Sons (and in some cases, Daughters) of Liberty, active throughout the colonies, organize protests, print leaflets, burn stamps, and lead attacks on stamp offices. British stamp officers are tarred and feathered. The colonists unite in a major boycott of British goods. and fledgling attempts at political unification to outright disregard for laws, mob riots, and radical protests such as the Boston Tea Party. When protest proved successful with the repeal of the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts, the colonists learned of Britain’s dependence on American business and the political strength gained in colonial unity. In 1774 Britain hardened its response to the increasing rebelliousness with the blockade of Boston Harbor. The colonists further unified as the First Continental Congress urged the formation of local militias, setting the stage for the War for Independence. 1770 The Boston Massacre takes place when British soldiers kill five colonists during protests against the Townshend Acts. The incident further incites colonial opposition to British rule. 1773 Protesting the tea tax imposed by the Townshend Acts, radicals led by Samuel Adams dump chests of tea into Boston Harbor in what is now known as the Boston Tea Party. The protest sparks “tea parties” in New York, Philadelphia, and other colonial ports. 1774 Britain responds to the Boston Tea Party by passing a series of laws known as the Coercive Acts, followed by the Quebec Act. The combined laws, nicknamed the “Intolerable Acts,” include the Massachusetts Government Act, which changes the colony’s original charter to give more power to Massachusetts’s governor. The Boston Port Act closes Boston to all trade, leading to food shortages. As a show of support for the rebels of Massachusetts, South Carolina sends money and rice and New York sends sheep. Virginia’s House of Burgesses declares a statewide day of fasting. 1765 The Quartering Act requires colonists to provide funds for British troops and to house troops in private homes on demand. New Yorkers refuse to obey and the New York Assembly is temporarily dissolved the following year as punishment. 1766 As a result of successful protest and the persuasive words of American statesman Benjamin Franklin before Parliament, the Stamp Act is repealed. 1767 The Townshend Acts pass, putting an end to most long-term smuggling operations and further tightening British control of trade. The acts include the Suspending Act, under which the New York legislature is officially dismantled until funds are procured to pay for the quartering of British troops. They also include the Revenue Act, which places duties on tea, glass, paper, paint, and lead. Most Townshend Act duties will be repealed in 1770, but the tax on tea will remain. A Boston mob protests the Stamp Act. © Media Projects Incorporated Published by Facts on File Inc. All electronic storage, reproduction, or transmittal is copyright protected by the publisher. PRIOR TO 1763, GREAT BRITAIN did not involve itself greatly in the day-to-day functioning of colonial government. Domestic political dissent and various wars kept the British crown and Parliament distracted. After the Peace of Paris of 1763, Britain sought to consolidate its economic and political power over its colonies. Building on the economic monopoly created with the Navigation Acts (1650–1773), Britain passed in quick succession several measures of control, including the Sugar Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, and the Townshend Acts of 1767. Colonial rebellion against Britain’s tightening grip ranged from eloquent speeches, legal battles, economic boycotts,