White Paper: “Market Segmentation and Energy Efficiency Program

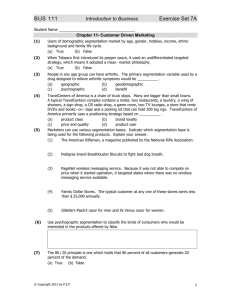

advertisement