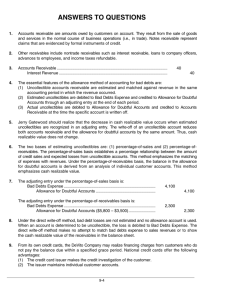

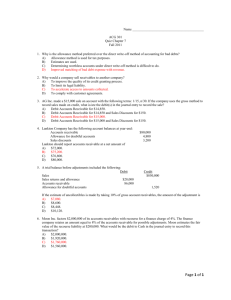

Revenue Recognition, Bad Debts, and Product Returns

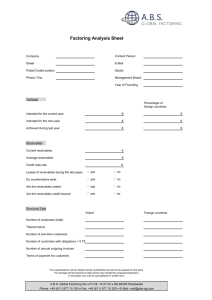

advertisement