Pork-barreling, Rent-Seeking and Clientelism - Royce Carroll

advertisement

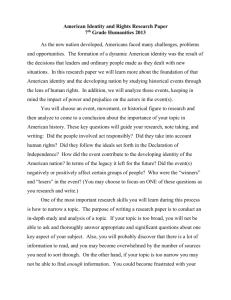

Pork-barreling, Rent-Seeking and Clientelism: Disaggregating Political Exchange Royce A. Carroll Rice University Department of Political Science- MS 24 P.O. Box 1892 Houston, TX 77251-1892 e-mail: rcarroll@rice.edu Mona M. Lyne Department of Political Science University of South Carolina Columbia, SC 29208 Phone: 803-777-7309 e-mail: lynemm@sc.edu September 2006 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, Ill., and the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, PA. Abstract Despite growing interest in the questions of how and why politicians deviate from national public goods provision, the study of narrow goods remains largely balkanized. Each of the major types of narrow goods and associated practices, including pork-barreling, rent-seeking, and clientelism is the subject of a distinct and typically self-contained literature. In this essay we seek to take an important step in the integration of these disparate literatures by identifying and differentiating commonly studied types of narrowly targeted goods and the associated political practices, and by providing clear analytic definitions that allow scholars to analyze these goods and practices in commensurable terms. Focusing on the nature of the political exchange involved, we present a typology accounting for both the scope (how targeted) and the ‘directness’ (how excludable) of delivery. Our typology provides an analytic basis for differentiating narrow political goods and practices that are easily conflated, explaining how even very “broad” policy may be “clientelistic” while even very narrow targeting may not. We provide examples of prominent puzzles that have proven intractable in the absence of a more complete typology such as the one we offer here. 2 Introduction Among the central concerns of comparative politics is the nature of policy provision in democratic societies. The longstanding question of when politicians will favor the provision of narrow goods with concentrated benefits and diffuse costs, rather than broad collective goods, has sparked several highly successful lines of research in the fields of legislative and electoral studies, political economy, and political development. These efforts to understand how politicians seek and maintain electoral advantages through the targeting of goods to narrow groups of beneficiaries have produced several related concepts – pork-barreling, rent-seeking and clientelism – which now occupy important roles in their respective literatures. With the post-war wave of democratization, early studies of democracy in the developing world sought to understand how representation and policymaking functioned in these new democracies. This research revealed a pervasive presence of political patterns characterized as clientelism, and still provides some of the most cogent analyses of the phenomenon.1 As many developing countries succumbed to authoritarianism in the 1960s and 70s, much succeeding research on political market failures focused upon advanced industrial countries, producing many of the canonical works on pork-barreling and rent-provision.2 Following the most recent wave of democratization in the late twentieth century, scholars have once again focused on clientelism, using case studies, formal models and statistical methods, extending the frontiers of the study of representation and patron-client politics.3 1 See for example, Almond and Coleman (1960), Almond (1958), Scott (1972), Powell (1970), Landé (1973), Kaufman (1974), Graziano (1976), Schmidt, et. al (1977). 2 The early canonical studies include, among others, Ferejohn (1974), Mayhew (1974), Fiorina (1977), Krueger (1974), Posner (1975), Peltzman (1976), Buchanan, et al. (1980). 3 On multi-country studies, see for example, Piattoni (2001), Kitschelt and Wilkinson (2007), and Schaeffer and Schedler (forthcoming). On formal models, see Stokes (2005), and on extensive new empirical tests see Jones (2005), Naoi (2006), 1 Each of these literatures has advanced our understanding of the different ways in which policy deviates from the provision of national public goods, but has typically done so in a disconnected fashion. As a result, our understanding of both the forms and the consequences of policies that “serve the few at the expense of the many” remains limited in important ways. Systematic analysis of the causes and the consequences of “particularism“ becomes more difficult in the absence of a framework that clearly distinguishes different forms of narrow goods provision. The central goal of this paper is to build a definitional framework that helps clear the underbrush and clarify relationships among different types of narrow goods provision. We believe this is an indispensible initial step toward the goal of developing a more unified analytic account of narrow goods provision. First, we provide a typology of political exchange relationships and apply it to several basic types of narrow goods provision identified by the literature. Often, national public policy and clientelistic private goods are implicitly considered polar opposites on what might be thought of as a particularistic “scale,” while rents, pork and other types of merely narrow policy lie between these two extremes. We emphasize instead the need two distinguish two dimensions: the scope of the targeted constituency and the directness of the exchange. With this distinction in hand, we can distinguish narrowly-targeted ‘rents’ such as tariffs, from mercantilist-type policies that may apply to a sector but that selectively distribute goods – such as production rights – among individual firms. Similarly, we draw a distinction between geographically targeted collective goods in the form of “pork,” and localized benefits provided to individuals on a selective basis within a restricted geographic scope. The utility of this framework lies in its ability to account for political exchange relationships that are clientelistic even when the policy has a very broad scope, as well as exchange Lindberg (2003), Taylor-Robinson (2006), and Diaz-Cayeros and Magaloni (2003). On developing new systematic and general measures of clientelism, see the chapters in Kitschelt and Wilkinson (2007). 2 relationships involving goods of quite narrow scope that are not made on the basis of exchanging political goods directly for votes. A Typology of Narrow Goods Provision Most theoretical work on political market failure has focused on the scope of the political goods supplied. Generally, broad collective goods are the point of departure and variations are conceived largely on the basis of the policy’s distributive impact. From this perspective, two canonical types of particularistic goods—rents and pork—would seem to capture the relevant effects of political market failure based on targeting sectoral or territorial groups, while clientelism simply represents the extreme of such narrowness.4 This simplification of the complex array of policy makes a variety of important analytical enterprises tractable, but also risks conflating very different types of policy. Emphasizing only the scope of beneficiaries does not differentiate policy very similar in terms of ostensibly targeting a sector or a territorial constituency but that varies considerably in terms of the type of political exchange taking place. To see why this is important, consider the introduction of a second dimension: the “direct” or “indirect” nature of the exchange. The distinction between direct and indirect exchange might be compared to that between barter and monetary exchanges. In a barter economy, partners to an exchange directly assess and exchange the goods—one type for another. In a monetary economy, partners to an exchange accept a symbolic representation of the goods they actually wish to exchange, and a future promise to honor that symbol, in order to address temporal discontinuities. 4 Often, such work implicitly emphasizes pork and rents, even while acknowledging clientelism. For a prominent example, see Cox and McCubbins’ (2001) influential work on the policy consequences of institutional design, which employs a single-dimensional framework along these lines to explain the “public-regardedness” or “private-regardedness” of policy. Similarly, studies emphasizing “distributive politics” tend to imply that policy varies along a single dimension of scope, and such work is usually built upon assumptions regarding the function of the electoral connection that imply what we here call “indirect exchange.” See Stokes (2005) for a discussion of how distributive models cannot account for direct, clientelistic exchange. 3 Like a barter economy, when political goods are exchanged directly there is no more to the exchange than the vote and the good that is received in return. In an indirect political exchange, on the other hand, the vote is given based on a symbolic promise to promote legislation aimed at achieving certain goals, be they distributive (pork or rents) or programmatic. Votes provided in an indirect exchange may be used to reward or punish politicians for any sort of outcome, or weighted combination of outcomes, be it overall policy performance or goods targeted to a territorial or sectoral group. Different voters might give varying weights to each and the same voter may vary the relative weight of different types of goods from election to election. These different types of exchange imply different types of delegation from voters to their representatives, and therefore may fundamentally shape our assumptions about representation in a given context. In a direct exchange, delegation is discrete. Politicians5 signal their ability and intention to reward supporters with immediate and excludable goods.6 Voters respond to credible claims, and trade their vote in a direct exchange with that politician, subject to renewal upon effective delivery. Although a politician may engage in any number of activities while in elected office, matters unrelated to the direct exchange are outside of this “contract.” Voters may value other outcomes, but to the extent voters depend on the relationship, the agent is freed from accountability for actions beyond the consistent delivery of the excludable good.7 5 We use the term “politicians” in order to generically refer to candidates, parties and other relevant elected actors. Although organizational forms are not our focus here, the variation behind our subsequent discussion is noteworthy. When seeking power through indirect exchange, politicians’ might wish to create an informative party reputation that tells constituencies what they can and will deliver in terms of collective goods or a personal reputation that indicates what they will deliver specifically to their local constituency. By contrast, the key problem for a strategy of direct exchange is identifying and monitoring contributions of support. Pre-existing social organizations, rather than parties, may provide a readily adaptable template to organize direct exchange and monitoring (Chandra 2004). In other cases, groups coming to power through force may abolish the social organizations used for clientelist organization by the vanquished--and political parties can serve as the new mass vehicle for clientelist organization. 6 For a discussion of how parties organize to signal their ability and willingness to provide private goods, see the papers in the Kitschelt and Wilkinson (2007) volume. On credibility, see Keefer (2005). 7 This is not to say that trades of votes for goods are simply one-off exchanges. Some exchanges, particularly those involving very low income voters, may be characterized by such one-shot interactions. The exchange relationship, however is iterated: the exchange is repeated and institutionalized such that relatively stable behavioral expectations are possible (Hawkins 2003). We will elaborate on this time dimension below when we discuss aggregation. 4 In an indirect exchange, voters delegate a representative role. Votes or other support is won on the basis of political platforms or pronouncements, representations of the legislation politicians will promulgate once in office, which may be programmatic or targeted to narrow groups, but not politically excludable within those groups. Political platforms, campaigns, and voting records allow politicians to signal their ability and intention to provide certain goods if elected—including narrowly targeted goods. Among these proposals, supporters choose those they find preferable and credible; politicians pursue policies given these electoral constraints. Narrow indirect exchanges account for the familiar forms of pork-barreling and rentprovision where particular segments of society benefit at the expense of the public. The more concentrated the benefits of a given policy, the more narrowly it is targeted—as is a single local school in comparison to a policy to allocate school construction funds across a region. Until we consider the directness of the exchange however, we do not know the political basis upon which such goods are provided. When we focus attention on the degree to which delivery is selective in our hypothetical polity, we find that the very same scope of goods may be provided not simply to seek, but rather to directly reward support. That is, as the exchange becomes more direct, access to goods may not be regulated only by geographical location or economic sector, but by political behavior in a form of quid pro quo. More counterintuitive, once we restrict our consideration to direct exchanges across the full range of scope, we can conceive of policies – such as development policy – designed to impact large segments of the population, not just local bailiwicks, but where the actual beneficiaries, in terms of production licenses and jobs, for example, are designated on the basis of a direct exchange of political support. 5 The Directness of Political Exchange Clientelism is widely studied, but as with other studies of narrow goods provision, the directversus-indirect nature of the link between voters and politicians is not always highlighted as an independent dimension from the narrowness of scope . Like scholars of indirect exchange, students of clientelism primarily conceptualize clientelism as diametrically opposed to national collective goods provision.8 Recent scholarship, however, has begun to reconsider this perspective.9 In one of the most important contributions to date on the subject, Kitschelt (2000) underscores direct exchange as the defining characteristic of clientelism. Politicians are not clientelist, Kitschelt notes, “as long as they disburse rents as a matter of codified, universalistic public policy applying to all members of a constituency, regardless of whether a particular individual supported or opposed the party that pushed for the rent-serving policy” (2000:850). The defining feature of clientelism is the presence of a quid pro quo, but the directness of exchange has even broader implications for our understanding of political market failure. Indirect exchange, even based on universalistic public policy, need not be built on programmatic linkages or broad groups. As we will discuss, indirect exchange includes both broad national collective goods like a stable currency, as well as instances of highly particularistic goods distributed to very narrow targeted groups, such as local infrastructure. At the same time, regardless of whether a policy is designed around a large group of any identity, if political goods are ultimately exchanged in a quid pro quo based on political support, ostensibly “group” or “national” policies can be indistinguishable from clientelism in function. Governments can designate that members of relatively large groups -- whether defined sectorally, territorially, or on ascriptive characteristics – as potential beneficiaries, but still only deliver them conditional on political support. To put it another 8 9 For an excellent review of some of the conceptual weaknesses of the early clientelist literature, see Kaufman (1974). See for example, Kitschelt (2000), Kitschelt and Wilkinson (2006), Warner (2001). 6 way, membership in a group is a necessary but not sufficient condition for receiving the benefits of direct exchange.10 While scholars who focused on political market failure in advanced industrial nations typically did not consider variation in the directness of political exchange (focusing on scope), those studying developing countries often were less concerned with the scope of the good (focusing on the nature of the exchange).11 Many scholars whose point of departure was the advanced democracies viewed targeting of narrow constituencies even in developing countries through the lens of rent-seeking and pork-barreling.12 At the same time, some work focused on developing countries suggested that if clientelism was necessarily a phenomenon of narrow distributional scope, national policy programs were by contrast essentially collective goods.13 Any given policy may fall anywhere on the dimension of narrowness. A regulatory policy or pork-barrel project may target a smaller or larger fragment of the population—ranging from a large industry or region, to a few firms or a single town. In the sections that follow, we use the distinction between direct and indirect exchange to understand the most commonly studied types of political market failure within which any given policy (with any degree of narrowness) may lie. We divide the following sections on qualitative grounds into four basic categories, shown in figure 1, divided by direct/indirect exchange and by the type of constituency, primarily to distinguish the indirect 10 It should be clear, then, that this distinction is not the same as that often made between “programmatic” and “particularistic”, as the latter could describe all of the practices we discuss below. Although similar to the notion of “public” and “private” goods in the abstract, the conflation of these terms with the physical nature of the good is something we wish to avoid here. Instead, we emphasize that it is the type of exchange that creates privateness. Direct exchange indeed implies the distribution of private goods, in the sense of access. As we shall note below, it is the access that defines the political nature of the good: goods that are apparently identical in form (for example, local educational services or utilities) can be delivered on an indirect or direct basis. 11 Of course, this analytic choice was typically due to focus on single case studies where these parameters do not change or have no external point of reference. As scholars increasingly emphasize cross-national studies, it is critical to take this dimension of variation explicitly into account. 12 A particularly prominent example is Krueger’s (1974) famous examination of “rents” in India and Turkey, which we will discuss more fully below. 13 For example, in his groundbreaking study of Chilean politics, Valenzuela (1977) considers ISI policy as a programmatic component to post-War Chilean parties’ appeal due its national scope. However, as we argue here, this relationship does not follow as a matter of course; a broad scope is not synonymous with collective goods or programmatic policy. 7 targeting of narrow groups with pork and rents from what we will call “sectoral” and “territorial” clientelism. In each section, we provide examples illustrating the range of narrowness that can be found within each type. [Figure 1 about here] As the implications for policy-making would seem to diverge so significantly across the dimension of directness of exchange, it is important to clearly distinguish highly particularistic indirect exchange from clientelism and identifying when general policy is implemented as a direct exchange. If one of the central goals of research on political market failure is to understand when and why politicians will provide narrow goods at the expense of national public policy, then attention must be given to distinguishing direct versus indirect exchange. “Pork Barrel” politics and Territorial Clientelism A long tradition of American political science has focused on pork barreling within the U.S. Congress (Fiorina and Noll 1978; Fiorina 1977, 1983; Weingast, Shepsle and Johnsen 1981; Ferejohn 1974). These studies focus on how individual politicians claim credit for providing locally targeted collective goods to their districts, despite the cost to other districts or for national policy. Voters, meanwhile, are aware of (or focus on) the benefits, but not the diffuse costs of this behavior. Even if doing away with pork barrel distributions has broad public appeal, members have no incentive to sacrifice their continuing access to a reliable mechanism of local reputation building (Mayhew 1974).14 These ideas have been adapted to countless comparative applications. As defined in these classical accounts, politicians distribute pork in search of but not in direct exchange for political support. Support may come either from the provision of the goods 14 More recent work, of course, tempers this traditional individualist view with the importance of the party label and associated national policy reputation even for a legislator’s own reelection in the U.S. (e.g. Cox and McCubbins 1993). 8 themselves, through cultivating a local voting constituency, or through the business it funnels to local interests, leading to campaign contributions. Given that narrow political considerations determine relative distributions of pork, it is almost always assumed to be inefficient in relation to a distribution of resources based on national social welfare alone. However, when legislators use pork primarily to build up a local voting constituency, pork-barreling may be efficient from a local social welfare standpoint—that is, it provides needed locally-targeted public goods like roads, hospitals, schools, etc. Diffuse costs and concentrated benefits typically conceal the social welfare losses of pork provision. The negative political consequences of pork provision manifest when the social costs become apparent to voters benefiting the least15 and competing political entrepreneurs have the means and will to clarify the source of such failures. Without focus on the direct or indirect dimension of narrowly targeted goods, all local targeting may appear similar and is often treated as such. Yet pork-barreling as defined above does not differentiate within the territorial constituency based on a quid pro quo and the costs are largely imposed on those outside the district (Ferejohn 1974). Indeed, the electoral theory of pork-barreling and cultivating a local voting constituency suggests there should be fierce competition to maximize the number of local beneficiaries. Though clientelism is well studied in isolation, little work has endeavored to distinguish fully between direct and indirect targeting of policy on a territorial basis. This may be due in part to observational equivalence between the legislative strategies aimed at delivering both pork-barrel and clientelistic goods to a territorial constituency. Legislators seeking resources to provide pork (locally-targeted public goods) and those seeking resources to trade locally in a direct exchange 15 Take for example, such tension over spending priorities in Japan in the late 1990s where "urban voters were outraged not only by the deepening recession but also by the way in which fiscal stimulus through public works benefited mostly rural constituencies but implied future tax hikes for all." (Mulgan 2003:175) 9 might behave quite similarly in the legislature, both avidly pursuing resources for their region or town. Thus, studies emphasizing particularism more generally tend to group such goods on the basis of their territorial nature, putting aside the direct or indirect quality of the exchange. Legislators pursuing either strategy will seek funds for their district or region with little regard for the costs imposed on other districts, or the effects on purported national policy goals. Detecting the difference in how funds are used often requires close attention to implementation strategies and how they are designed to organize political support (Kitschelt 2000). Thus differences between direct territorial exchange and pork barreling might appear as a matter of degree.16 Yet there is a very important difference of kind: pork-barreling does not exclude at the local level, while clientelism does. Any truly direct system of exchange must employ some system of determining whether recipients have indeed fulfilled their end of the agreement. The less accurate this accounting, the less “direct” the exchange, by definition. However, politicians are extremely resourceful when it comes to enforcing such arrangements in practice, even in the modern context of secret voting.17 Selective distribution may entail monopolizing the provision of goods demanded by local voters, such as a region’s supply of state jobs or a central aspect of the local economy, or it may mean devising ways to turn what appear to be local public goods into vehicles for direct exchange. As Greenfield (1972) documents, a road might be started, but never finished if votes are not reliably delivered over time to the state-level politicians with the power to order it finished. Similarly, Geddes (1994) discusses public works departments with no spare parts, and hospitals with no 16 See Brinkerhoff and Goldsmith (2002:6) for example, who differentiate between pork, as a locally targeted public good with “spillover benefits for the community” and the “purely private goods associated with clientelism,” but who argue that pork is a “variation of clientelism.” 17 As Brusco, Nazareno and Stokes (2003) explain: “parties compensate for their inability to observe the vote directly by observing a range of other actions and behaviors, actions and behaviors that allow party operatives to make good guesses about the vote choices of individuals.” In Argentina, the “operative can’t know with full certainty how people in his area of responsibility voted. But if his guesses are at least correlated with the voters’ actual choices, and if he then conditions the future flow of goods on support, the voter who wants the goods should vote for the clientelist party.” 10 medicine, which would appear to render the locally spent resources ineffectual as local public goods. Souza’s (1997) study of the Brazilian state of Bahia during the early 1990s provides an example of the use of political exclusion strategies in the area of local ‘public’ education. She found that head teachers at publicly funded schools were gubernatorial patronage appointments, education spending tracked with electoral cycles, and school construction in the state was disconnected from social demand, instead tied to the political needs of the governor’s local affiliates. In addition to the clientelistic use of these construction and staffing funds, however, access to the good was also based on direct exchange. As one ex-governor explained, “Children could register in a school only if they had a letter from a local politician, a state deputy or an influential politician” (Souza 1997:145). Alternatively, even short of monopolization, politicians in power may simply have such an overwhelming comparative advantage in providing a reliable supply of needed direct benefits that voters are inclined to perpetuate the relationship between their region’s elites and the state.18 However, the weaker the ability to enforce the political selectivity of policy, the less direct the political exchange. Legislators’ access to locally targeted resources can be more or less transparent and formalized. In the U.S., some localized federal spending is transparent while other is obtained through the rather opaque procedure of “earmarking,” in which provisions for locally targeted resources are inserted into bills after they have formally been approved. In both Brazil and 18 Komeito (1984), for instance, describes how constituency service became a direct exchange in Ireland even lacking monopoly, due to comparative advantage: “politicians were claiming personal credit for providing legal entitlements. However, politicians argued that, whatever the legal entitlements, the person would have received nothing without the politician's help. The broker's ‘profit’ derived from providing a service that was easy and quick for him, but difficult and time-consuming for an outsider. He thus hoped to create a debt at little actual cost to himself.” (Komeito 1984:182) A similar and common phenomenon in Latin America is the bureaucratic fixer. These fixers were licensed by the state to cut the red tape of the bureaucracy for those who are willing to pay a fee. Although citizens could petition the bureaucracy without paying a fee, the chances of a helpful response were so slim that most that had the money would pay a fixer to deal with the bureaucracy for them. These fixers were available for both trivial and serious needs for bureaucratic assistance, from dealing with minor traffic violations to ensuring receipt pensions. Constituency service as a form of local accountability exists in some form in every democracy, but its use as a currency for direct rather than indirect political exchange is the crucial distinction for its impact on general democratic accountability. 11 Colombia, there have been more transparent formal procedures by which legislators receive resources for their local districts. In Brazil, legislators can formally propose amendments to the budget for clearly specified local projects. In Colombia for many years, all legislators were allotted what were known as auxilios parlamentares, a fixed sum that each was entitled to spend in her local district.19 Although pork provision and clientelism both have social costs, all else equal (including the amount of targeted resources), distribution via direct exchanges should be considerably more socially costly than providing locally targeted pork because each voter (or group of voters) must be regulated in their benefit conditional on some aspect of the locality’s political behavior. The long literature on pork barreling in the modern U.S. provides considerable evidence that this locallytargeted spending is used to procure local public goods, although direct exchanges were more common earlier in the nation’s history and in certain geographical areas. In many other countries, particularly developing countries, it is less clear whether locally targeted resources become local public goods or currency for direct exchange. Clear distinctions between pork-barreling and clientelism would shed important light on why what current analysis concludes is the same emphasis on “localism” produces such extreme differentials in the level of collective goods provided, and social welfare costs incurred across democracies. A central reason for the conflation of pork-barreling and territorial clientelism20 is the lack of a straightforward, generalizable method for determining which strategy a given legislator or party is employing.21 Developing measures of clientelism at differing levels of aggregation is a crucial hurdle facing the advancement of cross-national scholarship on political market failure. Short of such 19 This was the practice until the 1991 revisions to the constitution. Also known as “broker clientelism” 21 Some recent work has made important progress, avoiding the common pitfall of conflating all local targeting. DiazCayeros and Magaloni (2003) argue that the PRI used the anti-poverty program called PRONASOL to provide locally targeted public goods in some districts, and to buy votes directly in other districts. Similarly, Stokes (2005) and Brusco et al. (2003) view the Peronists in Argentina after the recent transition to democracy as buying votes in some areas and providing local public goods in others. 20 12 measures, the distinctions noted above warrant a cautious analysis of empirical patterns that do not disaggregate direct and indirect exchange in territorial targeting. The label of ‘clientelism’ does not itself give us analytical leverage in understanding electoral or legislative politics unless it connotes a clear political distinction from ‘pork-barreling’ as just described. If constituencies can vote their choice without threat of exclusion from targeted goods, then no degree of narrowness makes the exchange truly direct. Conversely, if constituencies must demonstrate their political allegiances in order to obtain and preserve access to local goods, no amount of breadth in the formal goals of the associated policy makes the relationship any less direct. This becomes especially clear when clientelism is part of the implementation of policies with a sectoral scope, discussed in the next section. Interest Group Rents and Sectoral Clientelism Just as pork barreling involves targeting narrow territorial interests, indirect sectorally targeted goods, or “rents”,22 provide relatively narrow benefits to sectorally-defined constituencies via tariffs, regulatory rules and other types of subsidies that favor a particular sector of production. This definition of rents, like pork-barreling, entails non-excludability within the narrow group (Buchanan et al. 1980). Goods targeted to a narrow sub-national group that are a collective good for members of that group are sometimes called “club goods” (Buchanan 1980). These are not public or collective goods in the colloquial sense in that they are not designed to serve the “general interest” and instead provide subsidies to producers at consumers’ expense. Yet, from the point of view of these narrow groups, policies extracting rents from the majority are in fact a collective good 22 Note that we restrict our use of the term “rents” to sectorally narrow policy benefits obtained through formally legal means. Illegal provision of rents is discussed later. 13 in the strict sense.23 A tariff, for example, provides benefits to all producers in the product category and a typical regulatory intervention is formally universal--applying equally to the affected producers and any who might become producers.24 A number of prominent scholars concluded that the rent-seeking framework captures the relevant aspects of government interventions in the market around the globe. Krueger (1974), for example, in her classic work that coined the phrase “rent-seeking”, treats licensing and other interventions in India and Turkey as of the variety described by Kitschelt above—favoring some firms or sectors over others in practice, but formally based on some ostensibly neutral, developmentally-oriented criteria such as installed capacity. More recently, Lohmann (1998) argues that information asymmetry across different groups of voters can explain variation in the provision of rents to special interest groups across both developed and developing democracies. Many scholars rely on an exogenously determined market-orientation of export sector interests, as contrasted to the rent-seeking interests of the import-competing sector to explain policy choice. Thus, Sachs (1985) argues that the continued strength of the agricultural sector during the phase of industrial promotion led East Asian governments to opt for the more neutral exchange and trade regimes, which were the linchpin of their successful development policy.25 And new economic 23 A prominent example of club goods in the United States is the famed sugar lobby, which has succeeded in restricting imports of sugar for over two centuries. Notorious campaign contributors, sugar companies benefit from import quotas that raise US sugar prices to two to three times the world market rate, creating an additional $1 billion profit annually (Washington Post 4.16.05). Similarly, cotton growers receive $3 to $4 billion dollars a year in federal government subsidies (The New Republic 9.29.03). There are a plethora of such trade and regulatory interventions in every advanced industrial economy. 24 Club goods are referred to by economists as “excludable” in that they are designated to be practically available only to a narrow group—in these cases, an existing set of producers or a subset of the general population. While this is certainly a form of excludability in a broad sense (which we call the narrowness or “scope”), such exclusion is common to all of the types of narrow goods provision we treat here. Indeed, this commonality is at the root of tendencies to conflate all forms of narrow goods provision. As discussed above, our classification is political, emphasizing the presence or absence of direct exchanges in restricting access beyond the formal group designation. It is the selective delivery based on how one voted that determines whether apparently similar goods are de facto a “private” or “club.” 25 This linchpin of the comparative logic – the purported weakness of the Latin American agricultural sector – is debatable. See for example Balassa’s (1985) objections in the same volume. 14 historians have relied on a similar derivation of policy preferences to explain Latin America’s relatively poor economic performance over several centuries (Haber 1997 2002). These analyses do not clearly distinguish state interventions that produce narrow benefits that are non-excludable within the favored interest group from those characterized by direct delivery to firms within a sector in a quid pro quo.26 Just as an undifferentiated analysis of territorial targeting has substantial limitations, the single dimension of scope implicitly used in studies of sectoral targeting fails to capture variation across policies with very different effects on market production and development outcomes. The political economy literature on developing countries hints that an undifferentiated rentseeking analysis is problematic. For example, Bates (2001:71), de Soto (2000:102-3) and Little et al. (1971: 41) all emphasize that ISI producers were sheltered from both international and domestic competition, with the clear implication that these policies are more akin to mercantilism than to internally non-excludable, sectorally-targeted rents.27 These are clearly different from the sectorally targeted goods of indirect exchange, which do not confer such sectoral goods as production rights directly, but provide an advantage to whole groups. Though none of these authors systematically analyze the industrial policies of developing countries in contrast to the classical notion of rentprovision, their work suggests we need to give special consideration to policies ostensibly designed around an economic sector, but in fact supplied only in a quid pro quo. Once we differentiate collective goods for a favored sector from those akin to mercantilist policies we should expect clear differences in terms of the social welfare costs. 26 Krueger considers a direct quid pro quo in terms of an illegal bribe. But as we will discuss below, it is important to distinguish between resources obtained from narrow interests that enrich the politician personally, and resources that are employed in the electoral arena. Strictly defined, bribes are distinct from the electoral resources obtained from other gains derived from catering to narrow interests, in that they are designed to directly enrich the individual politician and not necessarily to influence elections. 27 De Soto makes the point explicitly that policies in developing countries are akin to European guilds, where the right to produce is a political right. 15 Even relatively mild tariffs or regulatory interventions can produce very large rents for producers, while the diffusion of costs across all consumers minimizes the impact on the average voter. This oft-cited characteristic of rents enables some form of rent provision in every democracy. How does this differ from sectoral targeting delivered through direct exchange, when political authorities single out firms, either directly through licensing, or indirectly through differential access to subsidies? The monographic literature provides numerous examples. Weingrod (1977:327-8), for example, describes how in Italy politicians assign loans and licenses to families of his supporters. In Mexico, Grayson (2000:382) recounts how import substitution industrialization became one of the pillars of clientelistic support for the PRI under Cardenas as “bureaucrats and politicians conferred contracts on businessmen, slashed the regulatory ‘red tape’ that complicated their lucrative deals, and obtained official approvals required for economic transactions.” Direct targeting of firms does more than provide a competitive edge, it confers monopoly or oligopoly profits on the selected few firms in official favor. All else equal, we would expect sectoral clientelism to generate greater costs to national social welfare than rent-provision because it affects the market-wide production of a given product. Rents handicap some producers, but they do not completely eliminate competitors’ ability to challenge existing producers on price and quality.28 Moreover, with this kind of policy, the right to produce is an exclusively political right, and is a function of government favor rather than market prowess. Using excludable implementation strategies, sectoral policy provides a mechanism to construct political coalitions on the basis of direct exchange on a broad scale under the guise of national policy. Post-War import substitution industrialization policies implemented across the developing world are especially worthy of rethinking in this light. Prominent analyses of developing countries treat ISI as either a national collective policy or one providing categorical club goods to 28 Consider, for example, the case of US auto manufacturers who were successfully challenged by Japanese producers heavily handicapped by export restraints. 16 import-competing sectors (Haggard 1990, Kaufman 1990, Valenzeula 1977). This treatment derives from the policy’s ostensible promotion of national development (Valenzuela 1977) or the presence of coherent sectoral policies that appeared to benefit import substituting capital and labor as a class (Haggard 1990, Kaufman 1990). Other analysts of ISI viewed its flaws as driven by indirect rents to interest groups (Frieden 1991, Sachs 1985, Krueger 1974). These characterizations are worth revisiting through the lens of direct exchange. A multicountry study of these policies by the National Bureau of Economic Research highlighted the general absence of universal, codified criteria for distributing incentives both between and within sectors. As Bhagwati states (Bhagwati 1978:91, emphasis added). “It is interesting to note that no import control authority among the countries studied ever attempted to lay down explicitly the rules in this regard [inter-firm allocations], and varying elements of executive discretion always remained, defying the analyst's ability to decipher what exactly were the criteria utilized in the end … It is noteworthy that in these studies the inter-firm variations in [domestic resource costs] were almost as large as the inter-industrial variations in [domestic resource costs]…” 29 Without clear and neutral codified rules, rents are likely to be distributed on an ad hoc and political basis, as this pattern of domestic resource costs suggests. If ISI were implemented as a targeted, but otherwise neutral sectoral policy, all firms in a given sector should be protected and subsidized, creating high variation in domestic resource costs across sectors, but low variation across firms within the same sector. If all firms in a given sector receive the same state subsidies and protection, then those that survive and prosper should exhibit similar domestic resource costs. If firms across the economy survive not based on their ability to compete on the relatively level playing field within 29 The two countries for which such data were available were India and Turkey. The data on intra-industry variation in effective protection rates in Brazil which were part of the Little, et al. study, supports the same conclusion. 17 a given sector, but instead by virtue of selective production rights that go only to politically connected firms within that sector, then it is no surprise that domestic resource costs vary substantially within sectors across the economy. The high variation in domestic resource costs across firms within a sector reflects the fact that individual firm survival is not determined by any kind of efficiency in producing within the given sector, but rather on the basis of direct exchange of political support for exclusive production rights. Though ISI is not often thought of as a clientelist strategy, production rights excludable at the firm level can provide an efficient mechanism for networking units of directly exchanged political support. The Level of Aggregation of Direct Exchange The strong association between clientelism and narrowness makes the notion of a “broad” direct exchange as just described especially counterintuitive. Disaggregated clientelism, in which a politician or “boss” constructs an independent system of monitoring votes and distributing benefits was closely associated with pre-modern social organization where a natural patron with organic ties to clients can emerge, typically on the basis of land ownership. Under this kind of traditional clientelism, a local landowner commonly provides directly for all the clients’ needs, and in return, the client votes for the landowner’s political allies and supports him in other ways. Direct exchange, however, should not be defined based on the ancillary characteristics of this traditional form of clientelism. For example, a feature commonly considered inherent in the practice, the deference and loyalty that typically accompanies traditional clientelism in the absence of patron competitors, is not an inherent or necessary characteristic of direct exchange. Emphasis on such extrinsic characteristics implies that clientelism only occurs in “traditional” societies. Much 18 recent work on the subject runs directly counter to this view (Roniger 2004, Piattoni 2001, Kitschelt 2000), characterizing clientelism simply as direct exchange, regardless of the presence or qualities of a personal relationship between the exchanging parties. Clientelism, broadly defined, is highly adaptable and politicians are typically capable of finding methods of distribution and monitoring that can function in the presence of modern innovations such as computerized voting and the anonymous urbanized voters of modern industrial societies. One need only consider the use of voting machinery that allows detection of pulling the “right” lever30 or, more recently, the practice of enforcement via camera-equipped mobile phones to appreciate the adaptability of the practice. While the ultimately individual nature of enforcement is intrinsic to direct exchange, disaggregated organization certainly is not. As a number of analysts have noted, as urbanization, industrialization and integration of national markets ensue, there is typically a natural progression to higher-order aggregation. Local patrons who excel at forging national ties and ensuring the steady flow of resources from the center to the locality emerge as the key brokers in nationally-integrated systems. What were once local patrons become brokers who “link” local constituencies to nationallevel patrons (Powell 1970; Martz 1997; Archer 1990). This process does not necessarily take place as a direct mapping of existing patron-client ties into a national network—it is a highly competitive selection process. Industrialization and the expansion of national markets also implies large scale migration to the cities, and expansion of the working and middle classes which results in large numbers of “floating” voters with no connection to traditional rural-based clientelist networks. The solution in some cases entailed institutionalization of direct exchange at high levels of aggregation on the basis of urban employment, and these types of exchanges were called urban clientelism or corporatism 30 This method was used in Chicago, where voting machines were designed such that pulling the “wrong” lever required voters to move their feet. Voters were carefully warned before entering the booth that in order to receive their good in return, there must be no “dancing” in the voting booth. 19 (Collier and Collier 1991; Kaufman 1977).31 These broad direct exchanges provide efficiency advantages in capturing votes for the politician, and bargaining advantages for the voters.32 In short, direct exchange relationships can encompass large groups and many sectors when groups of citizens vote as part of a quid pro quo arrangement with the state or a broker, rather than based on general policy outcomes or even a policy that serves the common interests of their sector or region. Such cases deviate from “traditional” clientelism only in that voters have delegated their role in forging the direct exchange to some broader organization—be they vote brokers in a region or elites in a corporatist arrangement with the state. Yet, the level of aggregation among clients does not change the essentially direct exchange relationship between patron and client. The local broker, state representative or corporatist leader who acts as broker metes out rewards and punishments to voters.33 Exchange between Narrow Groups and Politicians: The Electoral Connection Rent-seeking, pork-barreling, clientelism all share a key feature—groups benefit from narrow goods and reward politicians who supply the goods. As we have defined them, each form of narrow goods provision discussed above revolves around politicians’ search for electoral advantages. In this way they are distinct from personal corruption, where politicians typically provide benefits such 31 Although studies of corporatist labor unions were often dominated by analytic concerns other than the direct or indirect nature of the exchange, scholars of these organizations almost invariably mention their inability to pursue general categorical interests (we elaborate on this below in our discussion of the implications of clientelism for electoral incentives). They also commonly note the special name for the leaders of these organizations in each country, which connotes co-optation and subservience to government control and policy, rather than independent representation of labor interests. Also, studies of corporatist interest organizations in developing countries are dominated by studies of industrial worker unions, but careful studies of single systems have noted that corporatist interest organization encompasses white collar workers as well (Schmitter 1981). 32 For other important work on direct collective exchanges, or corporate clientelism, see Tarrow (1967), Weingrod (1968), and Powell (1970). 33 Because of the close connection between the two concepts, patronage is sometimes used as a general term to subsume clientelism and at other times connotes specifically the political use of government appointments. The practice itself is not our focus here, but patronage is a currency is widely used in constructing the aggregated direct exchanges we describe. 20 as obtaining a contract or job for a supporter and are in turn personally and materially enriched. In assessing the political consequences, it is useful to distinguish corrupt practices of personal enrichment from practices in which groups supply some means to improve the electoral fortunes of politicians. While bribery and other forms of corruption are sometimes considered “rent-seeking” by political economists, politicians provide sectoral rents as defined here in response to lobbying by interest groups, and the campaign support they receive from those groups is directed at the maintenance of political power. Similarly, politicians provide pork in hopes of securing support from a local constituency, as when they rely on “personal” votes (Cain et al. 1987, Carey and Shugart 1995) or wish to insulate themselves from negative national trends (Mayhew 1974). For parties as well, pork may help win votes in marginal districts or cultivate party strongholds (McGillivray 2004). Forms of direct exchange are also primarily designed to use the electoral process to obtain and maintain political power. Mercantilist production rights, a form of sectoral clientelism, are delivered in return for resources that are used to build clientelist networks. Rather than a form of corruption, direct licensing or other types of governmental support for specific firms may be considered legitimate or even necessary practices in developing countries.34 Similarly, locally targeted excludable goods delivered directly in return for the delivery of blocs of votes are usually part of an electoral strategy. In short, rents, pork and clientelism in electoral democracies may also provide politicians with indirect personal benefits, but unlike bribery, these practices are primarily designed to exploit and adapt to electoral institutions in the maintenance of political office. The distinction between direct and indirect exchange is therefore fundamentally connected to how elections operate and the policy priorities of politicians in winning them. When politicians 34 Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s recent declaration that it was not the government’s job to prop up failing firms was thus a newsworthy event. Similarly, Lopez Obrador, the 2006 PRD presidential candidate in Mexico prominently advertised that he would end the government practice of bailing out failing businesses if elected. 21 focus extensively on delivering pork, they satisfy constituent demands and improve their personal election prospects at the expense of the general public. When politicians provide rents to interest groups, they reward their backers in return for resources to enhance electoral prospects. At the same time, in indirect political exchanges, voters retain access to targeted goods and services even if voting against those who delivered them, as do sectors that cease to support politicians who have the provided rents from which they benefit. Voters and firms engaged in the direct political exchanges described above can also cast their vote for or against a given politician that may have provided the targeted political goods from which they have benefited. Unlike recipients of indirectly targeted pork and rents, however, doing so entails sacrificing access to excludable goods of potentially vital importance. The ability of politicians to politically orient and directly revoke access to goods, services and economic rights implies a fundamentally distinct electoral purpose for targeted goods provision. Conclusion Systematic analysis of the relationship between the parameters of political competition and politicians’ policy choices requires clear and commensurate analytic definitions of narrow goods and associated practices. Here, we have taken a step in this direction by emphasizing the importance of disaggregating the targeting of narrow policy on territorial or sectoral groups based on distinguishing direct and indirect political exchange. With the dimensions of scope and directness treated independently, it becomes clear not only that very narrow goods provision may not be clientelism, but that policies delivered by way of direct exchanges can be broad or even national in scope. From this perspective, it is clear that clientelism is not merely an extreme form of particularism, but a kind 22 of political exchange that can exist throughout a range of sectoral and territorially targeted policies. Such disaggregation, in the form of emphasizing political relationships, is central to a better understanding how of particularism can vary across democracies, in order to assess both its causes and consequences. 23 References Archer, Ronald P. 1990. “The Transition form Traditional to Broker Clientelism in Colombia: Political Stability and Social Unrest.” Working Paper #140, Kellog Institute for International Studies, University of Notre Dame Baron, David P. 1994. “Electoral Competition with Informed and Uninformed Voters.” American Political Science Review 88, 1. Bhagwati, Jagdish. 1978. Anatomy and Consequences of Exchange Control Regimes. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Brady, David W. 1988. Critical Elections and Congressional Policy Making. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press Brusco, Valeria, Marcelo Nazareno, and Susan Stokes, 2003 "Selective Incentives and Electoral Mobilization: Evidence from Argentina," Buchanan, James M. Robert D. Tollison and Gordon Tullock, eds. 1980. Toward a Theory of the Rent-Seeking Society. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. Cain, Bruce, John Ferejohn and Morris Fiorina. 1987. The Personal Vote. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Carey, John M. and Matthew Soberg Shugart. 1995. “Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote: A Rank Ordering of Electoral Formulas.” Electoral Studies 14, 4: 417-39 Chang, Ha-Joon. 2002. “The East Asian Model of Economic Policy.” In Huber, Evelyne, ed., Models of Capitalism. Lessons for Latin America. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. Diaz-Cayeros, Alberto and Magaloni, Beatriz. 2003. “The politics of public spending. Part II – The Programa Nacional de Solidaridad (PRONASOL) in Mexico” Background Paper for the World Development Report 2004 (World Bank). Drake, Paul. 1996. Labor Movements and Dictatorships: The Southern Cone in Comparative Perspective. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Drysdale, Peter and Amyx, Jennifer (eds) 2003. Japanese Governance: Beyond Japan Inc. New York and London: Routledge Ferejohn, John. 1974. Pork Barrel Politics: Rivers and Harbors Legislation, 1947-1968. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Fiorina, Morris P. (1977). Congress: Keystone of the Washington Establishment. New Haven: Yale University Press. 24 Fiorina, Morris, and Roger Noll. 1979. "Majority Rule Models and Legislative Elections." Journal of Politics 41: 1081-1104. Fox, Jonathan. 1994. “The Difficult Transition from Clientelism to Citizenship.” World Politics 46(2): 151-84. Frieden, Jeffry A. 1991. Debt, Development, and Democracy. Modern Political Economy and Latin America, 1965-85. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Grayson, George 2000 “Mexico”, In Howard J. Wiarda and Harvey F. Kline, Latin American Politics and Development, Sixth edition, Boulder: Westview Press Graziano, Luigi. 1976.‘A Conceptual Framework for the Study of Clientelistic Behaviour’, European Journal of Political Research 4: 149-74 Greenfield, S. 1972 "Charwomen, Cesspools, and Road Building” in Strickon, Arnold and Sidney Greenfield, eds. Structure and Process in Latin America: Patronage, Clientage and Power Systems. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. Joskow, Paul L. and Roger G. Noll. 1981. "Regulation in Theory and Practice: An Overview." In Studies in Public Regulation, ed. Gary Fromm. Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press. Haber, Stephen . 1997. "Introduction: Economic Growth in Latin American Historiography." In How Latin America Fell Behind. Essays on the Economic Histories of Brazil and Mexico, 1800-1914, ed. Stephen Haber. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Haber, Stephen. 2002. Crony Capitalism and Economic Growth in Latin America: Theory and Evidence Hawkins, Kirk. 2003. “The Logic of Linkages: Antipartyism, Charismatic Movements, and the Breakdown of Party Systems in Latin America.” Ph.D. dissertation, Duke University. Kaufman, Robert R. 1990. "How Societies Change Developmental Models or Keep Them: Reflections on the Latin American Experience in the 1930's and the Postwar World." In Manufacturing Miracles. Paths of Industrialization in Latin America and East Asia, ed. Gary Gereffi and Donald L. Wyman. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Kaufman, Robert. 1974. “The Patron-Client Concept and Macro-Politics: Prospects and Problems.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 16 (3):284-308. Kaufman, Robert 1977. “Corporatism, Clientelism, and Partisan Conflict: A Study of Seven Latin American Countries," pp. 109-48, en James M. Malloy, ed., Authoritarianism and Corporatism in Latin America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press Kitschelt, Herbert. 2000. “Linkages between Citizens and Politicians in Democratic Polities.” Comparative Political Studies 33(6/7):845–879 25 Kitschelt, Herbert and Steven Wilkinson eds. 2006 Citizen-Politician Linkages in Democratic Politics. NY:. Cambridge University Press Komito, Lee. 1984. “Irish Clientelism: A Reappraisal.” The Economic and Social Review 15(3):173–194. Krueger, Anne O. 1974. "The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society." American Economic Review 64: 291-303. Lindberg, Staffan. 2003. “It’s Our Time to Chop: Do elections in Africa feed neopatrimonialism rather than counter-act it?” Democratization 14(2). Little, I. M. D., Tibor Scitovsky and Maurice Scott. 1970. Industry and Trade in Some Developing Countries. A Comparative Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lohmann, Susanne. 1998. “An Information Rationale for the Power of Special Interests.” American Political Science Review 92, 4: 809-827. Lynch, G. Patrick. (1999) “Presidential Elections and the Economy 1872 to 1996: The Times They Are A Changin’ or the Song Remains the Same.” Political Research Quarterly 52(4):825-44 Mayhew, David. 1974. Congress: The Electoral Connection. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Medina, Luis Fernando and Stokes, Susan. 2002. “Clientelism as Political Monopoly.” Paper delivered at the 2002 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston, August 29-September Naoi , Megumi “A Resource Model of Clientelism: Provincial-level Analysis,” Paper delivered at the 2006 meeting of the Midwest Political Science Assoication, Chicago, April 21 Nelson, Douglas. 1988. "Endogenous Tariff Theory: A Critical Survey." American Journal of Political Science 32 (August): 797-837. Noll, Roger G. and Bruce M. Owen. 1983. The Political Economy of Deregulation. Interest Groups in the Regulatory Process. Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. Peltzman, Sam. 1976. "Toward a More General Theory of Regulation." Journal of Law and Economics 21: 21140. Piattoni, Simona. 2001. Clientelism in Historical and Comparative Perspective. In Clientelism, Interests, and Democratic Representation, ed. Simona Piattoni. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Popkin, Samuel L. 1991. The Reasoning Voter. Communication and Persuasion in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 26 Powell, John Duncan. 1970. "Peasant Society and Clientelist Politics." American Political Science Review 64 (June): 411-25. Posner, Richard A. 1975. “The Social Costs of Monopoly and Regulation.” Journal of Political Economy 83: 807-27. Prebisch, Raul. 1963. “Towards a Dynamic Development Policy for Latin America,” New York: United Nations. Roninger, Luis 2004. ‘Political Clientelism, Democracy, and Market Economy’, Comparative Politics, 36(3), pp.353-375 Sachs, Jeffrey. 1985. “External Debt and Macroeconomic Performance in Latin America and East Asia.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2. Scheiner, Ethan 2005: Democracy without Competition in Japan. Opposition Failure in a One-Party Dominant State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Schmitter, Phillipe C. 1974. "Still the Century of Corporatism?" Review of Politics 36 (January): 85-131. Shugart, Matthew S. and John M. Carey. 1992. Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Souza, Celina (1997) Constitutional Engineering in Brazil: The Politics of Federalism and Decentralization. Houndmills e London: Macmillan; New York: St. Martin's Press Stokes, Susan and Luis Fernando Medina. 2002. “Clientelism as Political Monopoly.” Chicago Center on Democracy Working Paper #25. Stokes, Susan, and Luis Fernando Medina. 2006. “Monopoly and Monitoring: An Approach to Political Clientelism.” In Patrons or Policies? Citizen Politician Linkages in Democratic Politics. Herbert Kitschelt and Steven Wilkinson, eds. Cambridge Unversity Press. Stokes, Susan C. 2000. “Rethinking Clientelism.” Paper presented at the XXII International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, March 16-18, Miami, Florida. Stokes, Susan. 2001. Mandates and Democracy: Neoliberalism by Surprise in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press. Stokes, Susan. 2005. “Perverse Accountability: Monitoring Voters and Buying Votes.” American Political Science Review 99(3), 315–25. Stokes, Susan. 2004. “Is Vote-Buying Undemocratic?” Paper presented at the annual meeting of The American Political Science Association, Chicago, September 1-4. 27 Taylor-Robins, Michelle 2006. “The Difficult Road from Caudillismo to Democracy, or Can Clientelism Complement Democratic Electoral Institutions? The Honduran Case” on Informal Institutions and Democracy: Lessons from Latin America. Gretchen Helmke and Steven Levitsky, eds. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press Valenzuela, Arturo. 1977. Political Brokers in Chile: Local Government in a Centralized Polity. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. Warner, Carol. 2001. “Mass Parties and Clientelism in France and Italy” in Simona Piattoni, ed., Clientelism, Interests and Democratic Representation Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 28 Figure 1: Common Narrow Political Exchanges Type of Implementation Type of Legislative Targeting Territorial Sectoral I. Excludable Territorial Clientelism Sectoral Clientelism II. Nonexcludable Pork-barreling Rent-provision 29