Rethinking the Sutton Hoo Shoulder Clasps and

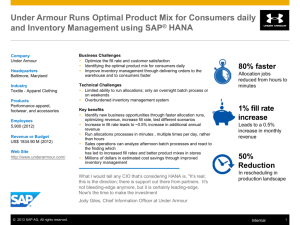

advertisement