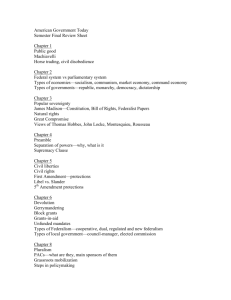

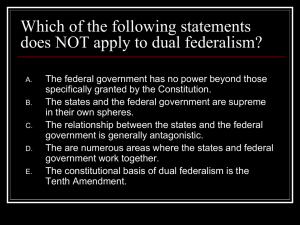

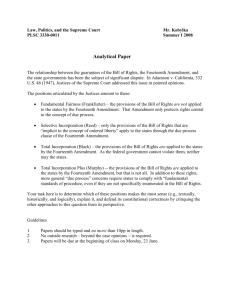

WHOSE FEDERALISM? - I.U. School of Law

advertisement