An Economic Analysis of the Norris-LaGuardia Act, the Wagner Act

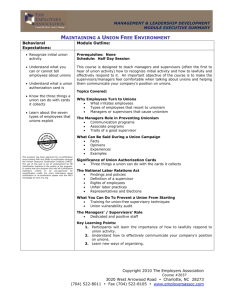

advertisement