Roman Fever Research Paper - Aubrey Zimmerman

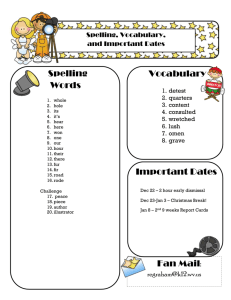

advertisement

Zimmerman 1 Aubrey Zimmerman English 2293 4 August 2011 The Mask Forged by Society in Edith Wharton’s “Roman Fever” Edith Wharton feeds from the stereotypical culture that society defines women in her short story, “Roman Fever.” Using the elements that which would normally mount women to their classified social position, such as knitting, Wharton embraces, yet conceals the dark secrets both women have between each other, whereas society almost would prefer the image of placid peace. In the story, the two women in mention are revisiting Rome for their daughters, both who are very curious themselves when they are introduced to the plot about to scurry off with two eligible Italian men. “Grace Ansley and Alida Slade, [two] middle-aged American widows who are not altogether good friends, in spite of knowing each other all of their lives, reminisce about their stay in Rome when they were young marriageable ladies” (Mortimer 189). Throughout the story this image of placid peace is displayed, but as the two women keep each other’s company, their past exploits are revealed amongst the two of them. Although the society seen in Wharton’s, “Roman Fever” view Alida Slade and Grace Ansley as the stereotypical, middle-aged American women, I contest that both women embrace their masks given by society to hide the bitter and passionate history built between them for over twenty-five years. First, the mundane act of knitting implies both logical, yet simple meaning and hidden, yet complex reason. The first curious aspect of knitting is “that the ladies are physically, emotionally, and intellectually incapable of nothing more than the traditionally passive, repetitive, and undemanding task of knitting” (Petry 163). The reader could entertain this act as simply what it is, but not for what it could be. One could contest that this act of knitting could Zimmerman 2 serve as the plot’s foil, simply because the rest of the story is placed around cancelling out the idea that these two women are the typical women society has defined them to be. Petry continues her point by stating: Wharton is predisposing the read to perceive the ladies as stereotypical matrons; and the rest of the story will be devoted to obliterating this stereotype, to exposing the intense passions which have been seething in both women for more than twenty-five years. The major rupture in this stereotype is the simple fact that…Alida Slade does not knit at all. This unexpected situation focuses the reader’s attention more intensely on Grace Ansley, whose apparently passionate devotion of knitting ultimately will enable us to probe the psyches of both women and to reconstruct the relationship of the generation before. (163-164) Provided that this act is only that: an act, it could be said that this said knitting could imply that Grace is simply more conformed to society’s rules, however, Wharton focuses on this act, although briefly, with as much importance as the conclusions drawn at the end of the selection. After being ridiculed by their own daughters for Grace’s knitting, Alida Slade says after their two daughters scanter off, “That’s what our daughters think of us” (Wharton 535)! Grace Ansley replies, “Not of us individually. We must remember that. It’s just the collective modern idea of Mothers…The new system has certainly given us a good deal of time to kill; and sometimes I get tired of looking—even at this” (Wharton 535). As Grace clearly rejects the image that society has painted how she should be, the story takes off to the crucial history between the two matrons. As the story shifts to the older mothers, it is becomes clear that their past may not be as grandiose as Wharton leads the readers to believe in the beginning. The two matronly women Zimmerman 3 share the same scandalous secret, but it is apparent that they allow each other the façade of acquaintanceship before Alida completely shifts their conversation to their past by easing the subject in the weight lingering between them. In the second part of the story and the two women are out for a walk, Mrs. Slade mentions, “‘I was just thinking…what different things Rome stands for to each generation of travelers. To our grandmothers, Roman Fever to our mothers, sentimental dangers—how we used to be guarded!—to our daughters, no more dangers than the middle of Main Street. They don’t know it—but how much they are missing’” (Wharton 538). One could believe that this quote holds more meaning than just a mother reminiscing her younger years with someone also familiar with the same experiences. In this quote, one could say, there is a vague sense of fondness, yet an introduction to the later robust animosity brought about by the revealing of their secrets. Alida simply reflects on how by the passing of each generation time changes things. This could mean that Alida, although still bitter about their past, has moved on and has possibly even forgiven Grace slightly. Back in their youth, both women were of marriageable age, which placed them as both competition as well as comrades in the same figurative battlefield. That sentiment describes them perfectly. Alida at the time was only engaged to Mr. Slade, although Grace Ansley was seemingly the object of his affections. “Their conversation leads to a reopening of old wounds, rivalry, renewed violence, and a series of revelations. Twenty-five years before, Alida Slade had forged a letter to Grace Ansley in the name of Alida's future husband, Delphin Slade, in order to get rid of Grace, who she knew was also in love with her husband-to-be” (Bauer 684). Through their conversation, the two women bear their confessions, neither party entirely innocent. Grace was the obvious other woman in Delphin’s life, but, in turn, Alida had been the one to write the Zimmerman 4 letter, which could have served to be more destructive than not. Bauer lends more detail on the issue of the letter: The letter sets up a rendezvous between Grace and Delphin in the Colosseum, though of course Delphin, according to Alida's plan, would not be there. That Alida says she knew Grace would not die of "Roman fever," even though Alida sends her to the Colosseum in the cold night air, does not diminish the essential violence of that letter. In a moment of forced contrition, Alida is willing to grant Grace this one possession-a memory, since Alida eventually married the man both of them loved and bore Delphin's legitimate child. (684) Although the letter backfired on Alida’s original plan to simply and discretely dispose of Grace Ansley for a while, so she would not interfere with Delphin or herself, for that matter, the reader is allowed a taste of sympathy offered from Alida. Bauer expands by saying, “Alida says Grace had nothing but a phony letter, while she herself had Delphin, his money, his name, and his child for twenty-five years. Grace retorts with the most effective comeback possible: the fact that she had Delphin's child, Barbara” (684). Throughout the life of Alida Slade, she probably felt a plethora of emotions, specifically remorse about how she stooped to write the letter that immediately mocked her for the rest of her life. As if time is the best dose of medicine, Alida seemingly matured and saw her side of the wrong, which is seen in the quote provided above. As Alida writes the letter, the weapon of choice in this selection, which in turn has a powerful result. Alida forces Delphin’s voice upon the page, which could be considered an act of violence against Grace and to herself, simply to fool her rival. And fool her rival she could have successfully done, had Grace not replied to the letter that was ostensibly written by a willing Delphin. And yet Alida had not one clue Grace would ever presume upon to reply to the false Zimmerman 5 letter. Precisely is thus what Grace’s rival cannot imagine: the reciprocity—the act of remembering what had been dismembered by the act of writing the letter (Bauer 685). The letter reflects the symbol of deceit and karma because it is how this last point was started in the first place. Also, the issue of Barbara is brought up in the very last statement said by Grace Ansley. “I had Barbara” (Wharton 543). In this nearly last line of the selection, the true weight of their shared secret and history is aroused. Rachel Bowlby suggests that the line “is the clinching shock announcement. We take it to mean, as must Mrs. Slade, that sex took place that night at the Colosseum and that Delphin Slade was the father of Barbara Ansley” (38). All of the hints that Wharton has dropped throughout the short story seem to weave smoothly together with this critical piece of information. Because Alida wrote the letter to spite Grace, her rival of the time, it clearly makes sense that she was to receive a dose of her own and that Grace would receive a part of Delphin to keep with her always. Bowlby continues her point by stating: The scandalous information then appears to sort out several doubts and suspicions that Wharton has carefully planted during the course of the narrative… If Barbara is now shown to be Delphin’s daughter, then these anomalies seem to be cleared up: Grace was quickly married because she was pregnant, and Barbara is after all the daughter of the dynamic Delphin Slade. (38). There is another issue that needs attention—Alida’s desire to control Grace’s life, or otherwise known as revenge over Grace for having an interest in her fiancé. The presence of each other in the other’s lives has been resolute. Alida may have had Delphin for a husband, but Grace received Alida’s dream daughter and even a piece of Delphin she would never receive. Zimmerman 6 Alida had sent that letter to Grace because she’d intended it to lead to a long, lonely wait at the Colosseum, yet the act had brought about the opposite of what she’d intended: a rendezvous with the two lovers. Presently, Alida had been unaware of what happened between Grace and Delphin as the result of her letter (Bowlby 39). This proves that the letter was suppose to hang over Grace’s life and allow Alida some control over the rival’s life. Yet the fact that it had brought about not only a coupling between the woman she was so eager to dispose of and the man she was engaged to, displays a sardonic irony that is nearly laughable. Finally, the mere title is more obtrusive than naught. This is so because “Roman Fever” was similar to malaria and is very much a double entendre in the sense that the Roman fever is symbolic to the passion that lingers beneath the text of the story, also between the two leading roles of the story. Alida was jealous of Grace and how she loved Delphin, which was what sparked the writing of the letter in the first place and that passion transmitted between the two women. Alida has more to be jealous of since the mention of Barbara being Delphin’s, as she is the daughter she so covets for herself. The title serves as the disease similarly known to be love, passion, and hostility, which both Alida Slade and Grace Ansley were victim to in one way or another. Grace was victim to the Roman fever when she was passionately in love with Delphin. Alida was the victim of hate, a passion more loud than love, and jealousy toward Grace and her daughter. It is clear that Alida covets more than Grace’s feelings for her late husband. Perhaps, in context, she knew that Delphin loved Graced and not her, provided the right source of analysis. The story does not end as abruptly as it shows in context. Seen in the many hints that both daughters, half-sisters, rather, are exactly like their mother’s opposite, it could be possible that the conclusion that Edith Wharton was trying to suggestively make is that history repeats itself. Perhaps the two daughters would make the same fateful mistake as their predecessors had Zimmerman 7 before them. And yet, perhaps they would be different. Wharton’s abrupt end in the story, or cliffhanger, does not mean that their story has ended. In the times reread, the story opens new doors each time one scrolls through the pages. Such animosity that lingered between the two women and the passion it ignited upon meeting again leads one to think that they depended on outward appearances for the sake of their secret. Clearly, the two did not simply lash out at each other, but eventually guided each other into the conversation. I believe that their images of how they knew they should be was what kept their pent-up secrets intact for so long. Zimmerman 8 Works Cited Bauer, Dale M. “Edith Wharton's ‘Roman Fever’: A Rune of History.” College English. Vol. 50, No. 6 (Oct., 1988): 681-693. JSTOR. Web. 3 Aug. 2011. Bowlby, Rachel. "I Had Barbara": Women's Ties and Wharton's "Roman Fever." Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 17.3 (2006): 37-51. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 3 Aug. 2011. Mortimer, Armine Kotin. “Romantic Fever: The Second Story as Illegitimate Daughter in Wharton's ‘Roman Fever’.” Narrative. Vol. 6, No. 2, (May, 1998): 188-198. JSTOR. Web. 3 Aug. 2011 Petry, Alice Hall. "A Twist of Crimson Silk: Edith Wharton’s ‘Roman Fever’." Studies in Short Fiction 24.2 (1987): 163. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 3 Aug. 2011. Wharton, Edith. “Roman Fever.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Shorter 7th ed. Vol 2. Ed. Nina Baym; et al. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008. 534-543. Print.