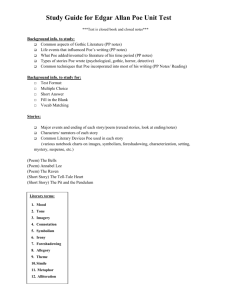

Musical Elements in Edgar Allan Poe's

advertisement