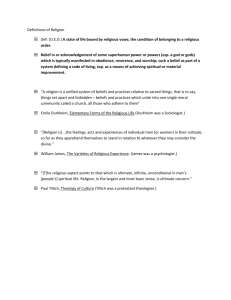

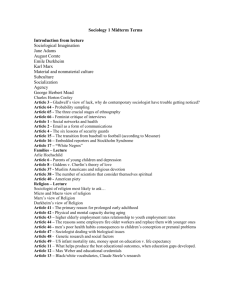

The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912) [Excerpt from

advertisement