Normality and pathology

advertisement

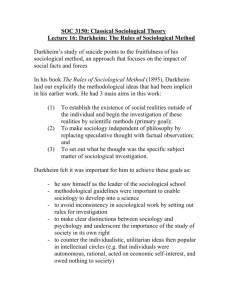

Anthony Giddens: Capitalism and modern social theory. Cambridge University Press, 1971. str. 91-94 Normality and pathology A substantial section of The Rules is devoted to an attempt to establish scientific criteria of social pathology. Durkheim's discussion here is a direct development of his concerns in his early articles, and is indeed of pivotal importance through the whole of his thought. Most social theorists, Durkheim points out, hold the view that there is an absolute logical gulf between scientific propositions (statements of fact) and statements of value. In this conception, scientific data can serve as a technical ' means' which can be applied in order to facilitate the attainment of objectives, but these objectives themselves cannot be validated through the use of scientific procedures. Durkheim rejects this Kantian dualism on the basis of denying that the division between ' means ' and ' ends ' which it presupposes can in fact be substantiated. For Durkheim, the abstract dichotomisation of means and ends involves similar errors in the sphere of general philosophy to those embodied in a more concrete way in the utilitarian model of society: namely, that both the ' means ' and the ' ends ' which men follow are empirically an outcome of the form of society of which they are members. Every means is from another point of view, itself an end ; for in order to put it into operation, it must be willed quite as much as the end whose realisation it prepares. There are always several routes that lead to a given goal; a choice must therefore be made between them. Now, if science cannot aid us in the choice of the best goal, how can it inform us which is the best means to reach it? Why should it recommend the most rapid in preference to the most economical, the surest rather than the simplest, or vice versa? If science cannot guide us in the determination of ultimate ends (fins superieures), it is equally powerless in the case of those secondary and subordinate ends which we call means. 39 The dichotomy between means and ends can be bridged, in Durkheim's view, by application of similar principles to those which govern the separation of ' normality' and ' pathology ' in biology. Durkheim admits that the identification of pathology in sociology poses peculiarly difficult problems. He therefore seeks to apply the methodological precept employed earlier: what is normal in the social realm can be identified by the ' external and perceptible characteristic' of universality. Normality, in other words, can be determined, in a preliminary way, with reference to the prevalence of a social fact within societies of a given type. Where a social phenomenon is to be found within all, or within the majority, of societies of the same societal type, then it can be treated as ' normal' for that type of society, except where more detailed investigation shows that the criterion of universality has been misapplied. A social fact, then, which is ' general' to a given type of society is ' normal' when this generality is shown to be founded in the conditions of functioning of that societal type. This may be illustrated by reference to the main thesis of The Division of Labour. Durkheim shows in that work that the existence of a strongly defined conscience collective is incompatible with the functioning of the type of society which has an advanced division of labour. The increasing preponderance of organic solidarity leads to a decline in the traditional forms of belief: but precisely because social solidarity becomes more dependent upon functional interdependence in the division of labour, the decline in collective beliefs is a normal characteristic of the modern type of society. In this particular case, however, the preliminary criterion of generality does not supply an applicable mode of determining normality. Modern societies are still in a period of transition; traditional beliefs continue to be important enough for some writers to claim that their decline is a pathological phenomenon. The persisting generality of these deliefs is not, in this instance therefore, an accurate index of what is normal and what is pathological. Thus in times of rapid social change, ' when the entire type is in process of evolution, without having yet become stabilised in its new form', elements of what is normal for the type which is becoming superseded still exist. It is necessary to analyse ' the conditions which determined this generality in the past and ... then investigate whether these conditions are still given in the present'.49 If these conditions do not pertain, the phenomenon in question, although ' general', cannot be called ' normal'. The calculation of criteria of normality in relation to specific societal types, according to Durkheim, allows us to steer a course in ethical theory between those who conceive history as a series of unique and unrepeated happenings, and those who attempt to formulate transhistorical ethical principles. In the first view, the possibility of any generalised ethics is excluded; in the second, ethical rules are formulated ' once and for all for the entire human species '. An example can be taken which Durkheim himself uses on many occasions. The sorts of moral ideas which pertained in the classical Greek polis were rooted in religious conceptions, and in a particular form of class structure based upon slavery: hence many of the ethical ideas of this period are now obsolete, and it is futile to try to resurrect them in the modern world. In Greece, for example, the ideal of the fully-rounded ' cultivated man', educated in all branches of scientific and literary knowledge, was integral to the society. But it is an ideal which is out of accord with the demands of an order based upon a high degree of specialisation in the division of labour. An evident criticism which might be made against Durkheim's position on this matter is that it induces compliance with the status quo, since it appears to identify the morally desirable with whatever state of affairs is at present in existence.41 Durkheim denies that this is so; on the contrary, it is only through definite knowledge of the potentially emergent trends in social reality that active intervention to promote social change can have any success. ' The future is already written for him who knows how to read it....'" The scientific study of morality allows us to distinguish those ideals which are in the process of becoming, but which are still largely hidden from the public consciousness. By showing that these ideals are not merely aberrations, and by analysing the changing social conditions that underlie them and which are serving to promote their growth, we are able to show which tendencies should be fostered and which need to be rejected as obsolete.43 Of course, science will never be complete enough to allow us to escape altogether from the necessity of acting without its guidance. ' We must live, and we must often anticipate science. In such cases we must do as we can and make use of what scientific observations are at our disposal...'" It is not the case, Durkheim argues, that the adoption of his standpoint renders all abstract ' philosophical' attempts to create logically consistent ethics completely futile. While it is true that' morality did not wait for the theories of the philosophers in order to be formed and to function', this does not mean that, given empirical knowledge of the social framework within which moral rules exist, philosophical reflection cannot play a part in introducing changes in existing moral rules. Philosophers, in fact, have often played such a role in history - but usually without consciously being aware of it. Such men have sought to enunciate universal moral principles, but have in fact acted as the precursors and progenitors of changes immanent in their society." 39 RSM, p. 48; RMS, p. 48. As an implicit criticism of Weber's view on this matter, this is a similar point to that made by Strauss. Leo Strauss: Natural Right and History (Chicago, 1953), p. 41. 40 RSM, P. 61. 41 Critics were not slow to make this assertion. Durkheim replied to three of his early critics in the AS, vol. 10, 1905-6, pp. 352-69. 42 Ibid. p. 368. 43 'The determination of moral facts', in Sociology and Philosophy (London, 1965), pp. 60flf. 44 Ibid. p. 67. RSM, p. 71. Marx makes a somewhat comparable point, discussing the innovatory character of criminal activity. Theories of Surplus Value (ed. Bonner & Burns), p. 376. 45