Sneak Preview - University Readers

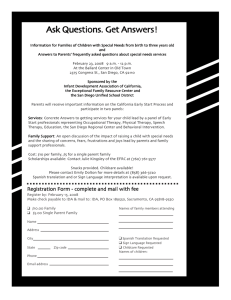

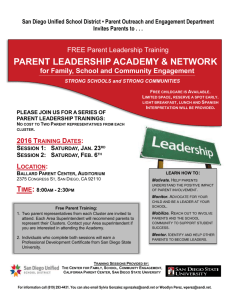

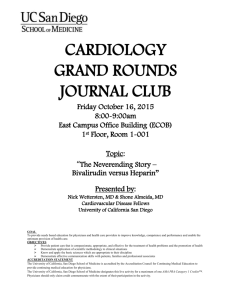

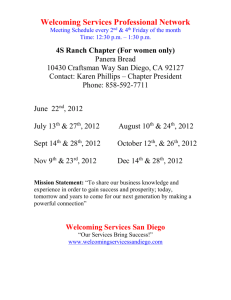

advertisement