Notes on Numbers

advertisement

Notes on

Numbers

2 0 1 6

E d i t i o n

Dr. Thomas L. Constable

Introduction

TITLE

The title the Jews used in their Hebrew Old Testament for this book comes from the fifth

word in the book in the Hebrew text, bemidbar: "in the wilderness." This is, of course,

appropriate since the Israelites spent most of the time covered in the narrative of

Numbers in the wilderness.

The English title "Numbers" is a translation of the Greek title Arithmoi. The Septuagint

translators chose this title because of the two censuses of the Israelites that Moses

recorded at the beginning (chs. 1—4) and toward the end (ch. 26) of the book. These

"numberings" of the people took place at the beginning and end of the wilderness

wanderings, and frame the contents of Numbers.

DATE AND WRITER

Moses wrote Numbers (cf. Num. 1:1; 33:2; Matt. 8:4; 19:7; Luke 24:44; John 1:45; et

al.). He apparently wrote it late in his life, across the Jordan from the Promised Land, on

the Plains of Moab.1 Moses evidently died close to 1406 B.C., since the Exodus happened

about 1446 B.C. (1 Kings 6:1), the Israelites were in the wilderness for 40 years (Num.

32:13), and he died shortly before they entered the Promised Land (Deut. 34:5).

There are also a few passages that appear to have been added after Moses' time: 12:3;

21:14-15; and 32:34-42. However, it is impossible to say how much later.

SCOPE AND PURPOSE

When the book opens, the Israelites were in the second month of the second year after

they departed from Egypt (1:1). Yet in chapters 7—10 we read about things that

happened in the nation before that time. Those events happened after Moses finished

setting up the tabernacle, which occurred on the first day of the first month of the second

year (7:1; cf. Exod. 40:17). When Numbers closes, the Israelites were in the tenth month

of the fortieth year (cf. Deut. 1:3). Thus the total time Numbers covers is about 39 years.

1See

the commentaries for fuller discussions of these subjects, e.g., Gordon J. Wenham, Numbers, pp. 21-

25.

Copyright © 2016 by Thomas L. Constable

Published by Sonic Light: http://www.soniclight.com/

2

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

Numbers records that the Israelites traveled from Mt. Sinai to the plains of Moab, which

lay to the east of Jericho and the Jordan River. However, their journey was not at all

direct. They proceeded from Sinai to Kadesh Barnea on Canaan's southern border, but

failed to go into the Promised Land from there because of unbelief. Their failure to trust

God and obey Him resulted in a period of 38 years of wandering in the wilderness. God

finally brought them back to "Kadesh" (short for "Kadesh Barnea"), and led them from

there to the Plains of Moab, that lay on Canaan's eastern border.

Even though the wilderness wanderings consumed the majority of the years that Numbers

records, Moses passed over the events of this period of Israel's history fairly quickly. No

one knows for sure how much time the Israelites spent in transit during the 38 years

between their first and last visits to Kadesh Barnea. God's emphasis in Numbers is first

on His preparation of the Israelites to enter the land from Kadesh (chs. 1—14), and lastly

on His preparation of their entrance from the Plains of Moab (chs. 20—36). This

indicates that the purpose of the book was primarily to show how God dealt with the

Israelites as they anticipated entrance into the Promised Land. It was not to record all the

events, or even most of the events, that took place in Israel's "wilderness wandering"

history. This selection of content, presented to teach spiritual lessons, is in harmony with

the other books of the Pentateuch. Their concern, too, was more theological than

historical.

Where Numbers Concentrates its Emphasis

The

Exodus

40 Years of Wilderness Wanderings

14

chs

5

chs

Entrance into the

Promised Land

17

chs

The Number of Chapters in Numbers

"The material in Numbers cannot be understood apart from what precedes

it in Exodus and Leviticus. The middle books of the Pentateuch hang

closely together, with Genesis forming a prologue, and Deuteronomy the

epilogue to the collection."2

The content in Numbers stresses events leading to the destruction of the older generation

of Israelites in the wilderness, and the preparation of the new generation for entrance into

the land. The census at the beginning of the book (chs. 1—4), and the one at the end

(ch. 26), provide: ". . . the overarching literary and theological structure of the book of

Numbers."3

2Ibid.,

pp. 15-16.

T. Olson, The Death of the Old and the Birth of the New: The Framework of the Book of Numbers

and the Pentateuch, p. 81.

3Dennis

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

"We may also venture the purpose of the book in this manner: To compel

obedience to Yahweh by members of the new community by reminding

them of the wrath of God on their parents because of their breach of

covenant; to encourage them to trust in the ongoing promises of their Lord

as they follow him into their heritage in Canaan; and to provoke them to

worship of God and to the enjoyment of their salvation."4

"The Book of Numbers seems to be an instruction manual to post-Sinai

Israel. The 'manual' deals with three areas: (a) how the nation was to order

itself in its journeyings, (b) how the priests and Levites were to function in

the condition of mobility which lay ahead, and (c) how they were to

prepare themselves for the conquest of Canaan and their settled lives there.

The narrative sections, of which there are many, demonstrate the successes

and failures of the Lord's people as they conformed and did not conform to

the requirements in the legislative, cultic, and prescriptive parts of the

book."5

GENRE

The basic genre of Numbers is narrative, though there are legal and genealogical sections

as well, that supplement the narrative. One scholar identified 14 different genres in the

book.6 However, most of it is narrative and legal material, and the overarching genre is

instructional history designed to teach theology.7

STYLE

"The individual pericopes of Numbers manifest design. Their main

structural device is chiasm and introversion. Also evidenced are such

artifices as parallel panels, subscripts and repetitive resumptions,

prolepses, and septenary enumerations. The pericopes are linked to each

other by associative terms and themes and to similar narratives in Exodus

by the same itinerary formula."8

THEME

I believe the theme of the book is obedience.

"The major theological theme of Numbers is reciprocal in nature: God has

brought a people to Himself by covenant grace, but He expects of them a

wholehearted devotion. Having accepted the terms of the Sinai Covenant,

Israel had placed herself under obligation to obey them, a process that was

4Ronald

B. Allen, "Numbers," in Genesis-Numbers, vol. 2 of The Expositor's Bible Commentary, p. 662.

H. Merrill, "Numbers," in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: Old Testament, p. 215.

6Ibid., p. xiii.

7Tremper Longman III and Raymond B. Dillard, An Introduction to the Old Testament, p. 95.

8Jacob Milgrom, Numbers, p. xxxi.

5Eugene

3

4

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

to begin at once and not in some distant place and time (Exod. 19:8;

24:3)."9

OUTLINE

I.

Experiences of the older generation in the wilderness chs. 1—25

II.

A.

Preparations for entering the Promised Land from the south chs. 1—10

1.

The first census and the organization of the people chs. 1—4

2.

Commands and rituals to observe in preparation for entering the

land chs. 5—9

3.

The departure from Sinai ch. 10

B.

The rebellion and judgment of the unbelieving generation chs. 11—25

1.

The cycle of rebellion, atonement, and death chs. 11—20

2.

The climax of rebellion, hope, and the end of dying chs. 21—25

Prospects of the younger generation in the land chs. 26—36

A.

Preparations for entering the Promised Land from the east chs. 26—32

1.

The second census ch. 26

2.

Provisions and commands to observe in preparation for entering

the land chs. 27—30

3.

Reprisal against Midian and the settlement of the Transjordanian

tribes chs. 31—32

B.

Warning and encouragement of the younger generation chs. 33—36

1.

Review of the journey from Egypt 33:1-49

2.

Anticipation of the Promised Land 33:50—36:13

J. Sidlow Baxter outlined Numbers as follows:10

I.

The old generation (Sinai to Kadesh) chs. 1—14

A.

The numbering chs. 1—4

B.

The instructing chs. 5—9

C.

The journeying chs. 10—14

The transition era (wandering in the wilderness) chs. 15—20

The new generation (Kadesh to Moab) chs. 21—34

A.

The new journeying chs. 21—25

B.

The new numbering chs. 26—27

C.

The new instructing chs. 28—34

II.

III.

9Merrill,

10J.

"Numbers," in The Old Testament Explorer, p. 98.

Sidlow Baxter, "The Book of Numbers," in Explore the Book, 1:156.

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

MESSAGE

To formulate a statement that summarizes the teaching of this book, it will be helpful to

identify some of the major revelations in Numbers. These constitute the unique values of

the book.

The first major value of Numbers is that it reveals the "graciousness of God" to an extent

not previously revealed. We see God's graciousness in His dealings with Israel

throughout this book.

In the first section of Numbers (chs. 1—10), God's provision for His people stands out.

We see this in the order and purity God specified for the maintenance of the Israelite

camp. We see it in the worship God provided for in the camp. We also see it in the

movement God prescribed for the camp. God faithfully provided for the needs of His

people in these many ways as they prepared to enter the Promised Land.

In the second section of the book (chs. 11—21), God's patience with His people stands

out. When the Israelites failed to obey God, He did not desert them, but He disciplined

them in love. God's patience in dealing with the Israelites did not result from God's

weakness, but it was an evidence of His strength. God did not manifest carelessness

toward the Israelites by making them wander in the wilderness for 38 years. He

manifested carefulness as He used those 38 years to prepare the next generation to obey

Him.

God disciplined the people for their disobedience, but He always directed them toward

the realization of His purpose for them as He disciplined them. The years of wilderness

wandering were years of education rather than abandonment. God had similarly prepared

Moses for 40 years in the wilderness before the Exodus. Compare Jesus in the wilderness

for 40 days.

In the third section (chs. 22—36), God's persistence in bringing Israel to the threshold of

the land is prominent. God protected Israel from her enemies and provided for her needs.

Even though Israel had been unfaithful, God persisted in demonstrating faithfulness to

the nation He had chosen to bless (cf. 2 Tim. 2:12).

A second major value of this book is the revelation it contains of the gravity of

"unbelief." This is a revelation of man, whereas the first was a revelation of God.

Numbers reveals the seriousness of the sin of unbelief, which manifests itself in

disobedience. The Israelites struggled with unbelief throughout the book, but the most

serious instance of it took place at Kadesh Barnea (chs. 13—14).

Numbers reveals the roots of unbelief. There were two causes: a mixed multitude and

mixed motives.

The congregation consisted of a combination of believing Israelites and others who had,

for various reasons, joined themselves to the people of God: a mixed multitude. These

foreigners joined Israel first at the Exodus (Exod. 12:38), but we find them mixed in with

5

6

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

the Israelites throughout Israel's subsequent history (cf. Lev. 24:10-23). This "rabble" was

first to complain against God, and their murmuring spread through the camp like a plague

periodically (cf. 11:4). Is there a mixed multitude in Christendom? Yes, real mixed with

professing Christians.

The second cause of unbelief was the mixed motives of the Israelites. They wanted to

enjoy God's blessings, and even obeyed Him to a degree to obtain these. But they also

wanted things that God—in His love for them—did not want them to have (cf. Gen. 3).

The Israelites did not fully commit themselves to God (cf. Rom. 12:1-2). They did not

fully allow God to shape them into a nation that would fulfill His purpose for them in the

world. This too resulted in murmuring. They longed for what they had experienced in

Egypt, and preferred a comfortable life over the adventurous life to which God had called

them. Murmuring is the telltale evidence of selfishness. It arises from a lack of singleminded dedication to God. How are these mixed motives evident today? We see them in

discontent and worldly standards.

The message of Numbers is that everything depends on our attitude toward God. Our

attitude toward our opportunities and our circumstances reveals our attitude toward God.

If we are not content with what God has brought into our lives, it indicates we may want

something different for ourselves than what God wants for us.

When we face a challenge to our faith, we need to visualize the difficulty itself being

overshadowed by God's presence, power, and promises.

The alternative is to allow the difficulty to block our view of God. The influences of

unbelievers and our own double-mindedness will tend to make us behave as the Israelites

did. At these times of testing, remembering Israel's experiences in Numbers should help

us understand what is going on, to help us trust God and obey Him more consistently.

The message of Numbers is a message of "comfort," on the one hand.

Numbers teaches that the failures of God's people cannot frustrate His plans. In Exodus,

we saw that the opposition of God's enemies cannot defeat Him. In Numbers, we see that

the failure of His instruments cannot defeat Him, either. God's chosen instruments can

postpone God's purposes, but they cannot preclude them.

In Numbers, we also see that God always deals with His chosen instruments righteously.

He will bless the minority who are faithful to Him, even though they live among a

majority who are under His discipline for being unfaithful. We see this in God's dealings

with Caleb and Joshua. God honors the faithful. He will also faithfully work with those

He is disciplining for their unfaithfulness. He will encourage them to experience the

greatest blessing they can within the sphere of their discipline. We see this in His

dealings with the rebellious generation of Israelites. Furthermore, God will not overlook

those who have disobeyed Him, just because, or even if, they have established a record of

past obedience. He will discipline them, too. We see this in God's dealings with Moses.

Whereas God honors the faithful, He also disciplines the unfaithful.

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

Numbers further teaches us that God's provisions are always adequate for His people's

needs (cf. 2 Cor. 12:9). He sustained the Israelites in the wilderness. Their failures were

not a result of God's inadequate provision, but came from their own dissatisfaction with

His provision. God Himself is an adequate Resource for His people as they go through

life (cf. Exod. 14—17). We need to look to Him for our needs.

On the other hand, Numbers is also a message of "warning." Every believer and every

group of believers (e.g., a local church), from time to time, faces the same challenge to

their faith that the Israelites faced in the wilderness and at Kadesh. The crisis comes when

faith encounters obstacles that only God's supernatural power can overcome. The believer

should then proceed against these obstacles by placing simple confidence in God. Our

response will depend on whether we are willing to act on our belief that God's presence,

power, and promises can overcome them. We need to focus on God more than on

ourselves.

We can fail to realize all that God wants for us if we fail to trust Him. Let me challenge

you to attempt great things for God. Think big! In 1977, Chris Marentika started the

Evangelical Theological Seminary of Indonesia. As of November, 2002, the school had a

permanent campus, about 450 students, a Christian university with 2,500 students, 15

branch schools, students and graduates had planted over 1,000 churches, and seen 50,000

Moslems become Christians. All of this took place in the largest Moslem country in the

world—which is also persecuting Christians!

By way of review, Genesis expounds faith. Exodus reveals that faith manifests itself in

worship and obedience. Leviticus explains worship more fully. Numbers stresses the

importance of obedience.

Numbers shows the importance of obedience by revealing the roots, process, and fruits of

disobedience.11

J. Sidlow Baxter believed that the central message of Numbers may be expressed in the

words of Romans 11:22: "Behold then the kindness and severity of God."

"In Numbers we see the severity of God, in the old generation which fell

in the wilderness and never entered Canaan. We see the goodness of God,

in the new generation which was protected, preserved, and provided for,

until Canaan was possessed. In the one case we see the awful inflexibility

of the Divine justice. In the other case we see the unfailing faithfulness of

God in His promise, His purpose, His people.

"Closely running up to this central message of the book are two other

lessons—two warnings to ourselves; and these also may be expressed in

words from the New Testament. The first is a warning against

presumption. Turning again to the Corinthian passage which we have just

quoted in full (I Cor. x. 1-12), we find that this warning against

11Adapted

from G. Campbell Morgan, Living Messages of the Books of the Bible, 1:1:65-80.

7

8

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

presumption is the lesson which Paul himself sees in the book of

Numbers. After telling us that 'all these things happened unto them as

types' for us, he says: 'Wherefore, let him that thinketh he standeth take

heed lest he fall.'

"The second warning is against unbelief. In Hebrews iii. 19 we read: 'They

could not enter in (to Canaan) because of unbelief'; and then it is added—

'Let us therefore fear lest, a promise being left us of entering into His rest,

any of you should seem to come short of it.' And again: 'Take heed,

brethren, lest there be in any of you an evil heart of unbelief' (iii. 12).

"Thus the New Testament itself interprets the book of Numbers for us.

This fourth writing of Moses says: 1. 'Behold the goodness and severity of

God.' 2. 'Let him that thinketh he standeth take heed . . .' 3. 'Take heed lest

there be in you—unbelief.'"12

12Baxter,

1:162.

2016 Edition

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

Exposition

I. EXPERIENCES OF THE OLDER GENERATION IN THE WILDERNESS

CHS. 1—25

This first main section of the book records how God prepared the Israelites to enter the

Promised Land from Kadesh Barnea, and why they failed to achieve that goal. Numbers,

like Leviticus, is divisible into two parts. The first part of Numbers (chs. 1—25) focuses

on the experiences of the older generation of Israelites that left Egypt in the Exodus.

Part 2 of the book (chs. 26—36) deals mainly with the younger generation that entered

the Promised Land.

A. PREPARATIONS FOR ENTERING THE PROMISED LAND FROM THE SOUTH CHS.

1—10

The first 10 chapters in Numbers describe Israel's preparation for entering the land. There

is some similarity between these chapters and Exodus 16—19, which record preparations

to enter into covenant with Yahweh at Mt. Sinai.

". . . just as the way from Goshen to Sinai was a preparation of the chosen

people for their reception into the covenant with God, so the way from

Sinai to Canaan was also a preparation for the possession of the promised

land."13

Note again the phrase "just as the Lord had commanded Moses" that recurs throughout

these chapters (1:19; et al.). This obedient attitude contrasts with the attitude of rebellion

that grew over time and resulted in the Kadesh Barnea fiasco (11:1). This change in

attitude is even more important for us to observe than the census figures and the order of

march.

1. The first census and the organization of the people chs. 1—4

"The two censuses (chs. 1—4, 26) are key to understanding the structure

of the book. The first census (chs. 1—4) concerns the first generation of

the Exodus community; the second census (ch. 26) focuses on the

experiences of the second generation, the people for whom this book is

primarily directed. The first generation of the redeemed were prepared for

triumph but ended in disaster. The second generation has an opportunity

for greatness—if only they will learn from the failures of their fathers and

mothers the absolute necessity for robust faithfulness to the Lord despite

all obstacles."14

13C.

F. Keil and Franz Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament: Pentateuch, 3:1.

p. 701.

14Allen,

9

10

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

The muster of the tribes except Levi ch. 1

"Over 150 times in the Book of Numbers, it's recorded that God spoke to

Moses [v. 1] and gave him instructions to share with the people."15

This phrase ("the LORD spoke to Moses") appears many times in Exodus, in Leviticus,

and once in Deuteronomy, as well. In view of the frequency of this claim, it is

disappointing to note the following statement by a leading contemporary Jewish

historian:

"Even the most pious are recognizing that it does not detract one jot or

tittle from the richness and usefulness of the age-hallowed volume [i.e.,

the Bible] to admit that it is the record of an amazing people's spiritual

progress rather than an infallible document of divine origin. Stanley Cook

suggests that it deepens the value of the Bible and brings out its central

truths to regard it as 'man's account of the divine rather than a divine

account of man.'"16

The purpose for counting the adult males 20 years of age and older was to identify those

who would serve in battle when Israel entered the land (v. 3).17 This is clear from the fact

that the phrase "from twenty years old and upward, whoever was able to go to war," or its

equivalent, appears 14 times in this chapter (vv. 3, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38,

40, 42, 45; cf. v. 18). Entrance into the land should have been only a few weeks from the

taking of this census. Moses had taken another census nine months before this one (Exod.

30:11-16; 38:25-26), but the purpose of that count was to determine how many adult

males owed atonement money.

The primary purpose of the second census, in Numbers 26, was to count the soldiers

again, and to determine the size of the tribes for each tribe's land allotment. The census

described in Numbers 1 excluded the Levites, all of whom God exempted from typical

military service in Israel (vv. 49-50). It also excluded the "mixed multitude" of non-Jews

who accompanied the Israelites.

"Only true Israelites were allowed to fight Israel's battles. None of the

'mixed multitude' which came from Egypt with Israel were eligible. What

a lesson for us today, when all sorts of persons are allowed to serve in the

organized Church who are without the Divinely required spiritual pedigree

of the new birth!"18

The number of fighting men in each tribe counted was as follows:

15Warren

W. Wiersbe, The Bible Exposition Commentary/Pentateuch, p. 313.

Sachar, A History of the Jews, p. 10. He provided no documentation for his quotation of Cook.

17See Gershon Brin, "The Formulae 'From . . . and Onward/Upward' (m . . . whl'h/wmslh)," Journal of

Biblical Literature 99:2 (1980):161-71.

18Baxter, 1:166.

16Abram

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

11

Reuben

46,500

Ephraim

40,500

Simeon

59,300

Manasseh

32,200

Gad

45,650

Benjamin

35,400

Judah

74,600

Dan

62,700

Issachar

54,400

Asher

41,500

Zebulun

57,400

Naphtali

53,400

The total was "603,550" men (v. 46). Since each tribe's total figure ends in zero, it

appears that Moses must have rounded off these numbers. God was already well on the

way to making the patriarchs' descendants innumerable (cf. Gen. 15:5). However, the

large census numbers have posed a problem for thoughtful Bible students. How could so

many people have survived in the desert for so long? Many skeptical scholars have tried

to explain these very large numbers as being much smaller.19 The problem involves the

meaning of the Hebrew word eleph. This word has been translated "thousand," "unit,"

"clan," etc., as it appears in various contexts.

"In short, there is no obvious solution to the problems posed by these

census figures."20

I believe we should take eleph in census contexts as "thousands," until further

investigation clearly indicates that we should interpret it differently.

"It has been estimated that from two to three million people—including

Levites, aged persons, children, and women—comprised the camp."21

"It is in the context of developing a military organization for war that the

Levites are assigned their tasks in relation to the tabernacle. In a sense,

their military assignment is the care and transportation of the religious

shrine. Num. 1:49-53 clearly outlines the requirements for the militaristic

protection of the tabernacle by the Levites."22

19For

a summary of the ways commentators have sought to explain the very large census numbers as

smaller, see R. K. Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament, pp. 631-64; Allen, pp. 680-91; Philip J.

Budd, Numbers, pp. 6-9; Wenham, pp. 60-66; Timothy R. Ashley, The Book of Numbers, pp. 60-66;

Merrill, "Numbers," in The Bible, . . ., p. 217; David M. Fouts, "A Defense of the Hyperbolic Interpretation

of Large Numbers in the Old Testament," Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 40:3 (September

1997):377-87; idem, "The Incredible Numbers of the Hebrew Kings," in Giving the Sense: Understanding

and Using Old Testament Historical Texts, pp. 283-99; idem, "The Use of Large Numbers in the Old

Testament with Particular Emphasis on the Use of 'elep," (Th.D. dissertation, Dallas Theological Seminary,

1992); K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, pp. 263-65; the note on 1:21 in the NET

Bible.; and John W. Wenham, "The Large Numbers in the Old Testament," Tyndale Bulletin 18 (1967):1953.

20Idem, Numbers, p. 66.

21Elmer Smick, "Numbers," in The Wycliffe Bible Commentary, p. 115. See also idem, p. 116.

22John R. Spencer, "The Tasks of the Levites: smr and sb'," Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche

Wessenschaft 96:2 (1984):270.

12

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

The "Levites" were one of the 12 tribes of Israel. The Kohathites were one of three clans

within that tribe, and the "priests" were the descendants of Aaron's family within the

Kohathite clan. Moses and Aaron were Kohathites. Moses had functioned as Israel's

"high priest" before God appointed Aaron to that office. So the hierarchy of priests in

Israel's early history was: the high priest on top (Aaron and later one of his descendants),

the other priests below him (Aaron's other descendants), and lastly the Levites at the

bottom (the relatives of Aaron's descendants within the tribe of Levi). The Levites often

assisted the priests in their less important duties.

During the wilderness wanderings, the Levites carried the tabernacle and its furnishings

(1:47-54). They also guarded this sanctuary (1 Chron. 9:19), taught the Israelites the Law

(Deut. 33:8-11; Neh. 8:7-9), and led them in worshipping the Lord (2 Chron. 29:28-32).

The total impression of Israel's God that this chapter projects is that He is a God of order

rather than of chaos and confusion (cf. Gen. 1; 1 Cor. 14:40).

The phrase "the Lord spoke to Moses" (v. 1) occurs over 80 times in the Book of

Numbers.23

The placement of the tribes ch. 2

The twelve tribes—excluding the Levites—camped in four groups of three tribes each, a

different group on each of the tabernacle's four sides. The Aaronic family of priests and

the three clans of Levites camped on the four sides of the tabernacle, but closer to the

sanctuary than the other tribes (v. 17). This arrangement placed Yahweh at the center of

the nation—geographically—and reminded the Israelites that His rightful place was at the

center of their life—nationally and personally.

"The Egyptians characteristically placed the tent of the king, his generals,

and officers at the center of a large army camp, but for the Israelites

another tent was central: the sanctuary in which it placed God to dwell

among his people. From him proceeds the power to save and to defend,

and from this tent in the middle he made known his ever-saving will."24

"This picture of the organization of Israel in camp is an expression of the

author's understanding of the theology of the divine presence. There are

barriers which divide a holy God from a fallible Israel. The structure of the

tent itself and the construction of the sophisticated priestly hierarchy has

the effect, at least potentially, of emphasizing the difference and distance

between man and God. This is valuable to theology as a perspective, but

requires the compensating search for nearness and presence. The . . .

author sought to affirm this in and through his insistence that God is to be

found, tabernacled among his people, at the center of their life as a

community."25

23Walter

Riggans, Numbers, p. 6.

Maarsingh, Numbers: a practical commentary, p. 15.

25Budd, p. 25.

24B.

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

13

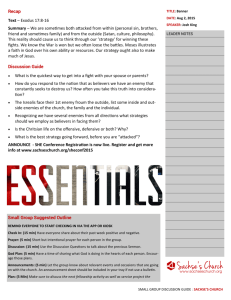

Locations of the Tribes around the Tabernacle

NORTH

Naphtali

Ephraim

Levites (Gershonites)

Manasseh

EAST

Issachar

Judah

Benjamin

Zebulun

Levites (Merarites)

Moses & Aaron & Other Priests

WEST

Dan

Asher

Levites (Kohathites)

Reuben

Simeon

Gad

SOUTH

The tribes that camped to the east and south marched ahead of the tabernacle, whereas

those on the west and north marched behind the tabernacle—whenever Israel was in

transit. The tabernacle faced "east" (i.e., "orient"), to face the rising sun, as was

customary in the ancient world.

"According to rabbinical tradition, the standard of Judah bore the figure of

a lion, that of Reuben the likeness of a man or of a man's head, that of

Ephraim the figure of an ox, and that of Dan the figure of an eagle . . ."26

The early Christians used these same symbols to represent the four Gospels: They used a

"lion" to stand for Matthew, an "ox for Mark, a "man" for Luke, and an "eagle" for John.

These animals symbolize various aspects of the life and ministry of Jesus Christ that each

evangelist stressed.

God evidently arranged the tribes in this order of encampment because of their ancestry.

26Keil

Judah, Issachar, Zebulun

Descendants of Leah

Reuben, Simeon, Gad

Descendants of Leah and her maid Zilpah

Ephraim, Manasseh, Benjamin

Descendants of Rachel

Dan, Asher, Naphtali

Descendants of the maids Bilhah and Zilpah

and Delitzsch, 3:17. Cf. Ezek. 1:10; Rev. 4:7.

14

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

"It will be seen from this arrangement that the vanguard and rearguard of

the host had the strongest forces—186,400 and 157,600 respectively—

with the smaller tribal groupings within them and the tabernacle in the

center."27

Moses did not explain the relationship of the individual tribes, that camped on each side

of the tabernacle, to the two other tribes on the same side. Some scholars believe they

were as my diagram above indicates, while others feel that Judah, Reuben, Ephraim, and

Dan were in the center of their groups.28

"Further, the placement on the east is very significant in Israel's thought.

East is the place of the rising of the sun, the source of hope and

sustenance. Westward was the sea. Israel's traditional stance was with its

back to the ocean and the descent of the sun. The ancient Hebrews were

not a sea-faring people like the Phoenicians and the Egyptians. For Israel

the place of pride was on the east. Hence there we find the triad of tribes

headed by Judah, Jacob's fourth son and father of the royal house that

leads to King Messiah."29

". . . the Genesis narratives devote much attention to the notion of 'the

east,' a theme that also appears important in the arrangement of the tribes.

After the Fall, Adam and Eve, and then Cain, were cast out of God's good

land 'toward the east' (3:24; 4:16). Furthermore, Babylon was built in the

east (Ge 11:2[, 9]), and Sodom was 'east' of the Promised Land (13:11).

Throughout these narratives the hope is developed that God's redemption

would come from the east and that this redemption would be a time of

restoration of God's original blessing and gift of the land in Creation.

Thus, God's first act of preparing the land—when he said, 'Let there be

light' (1:3)—used the imagery of the sunrise in the east as a figure of the

future redemption. Moreover, God's garden was planted for humankind 'in

the east' of Eden (2:8), and it was there that God intended to pour out his

blessing on them.

"Throughout the pentateuchal narratives, then, the concept of moving

'eastward' plays an important role as a reminder of the Paradise Lost—the

garden in the east of Eden—and a reminder of the hope for a return to

God's blessing 'from the east'—the place of waiting in the wilderness. It

was not without purpose, then, that the arrangement of the tribes around

the tabernacle should reflect the same imagery of hope and redemption."30

Baxter estimated that the quadrangle formed by some 2 million Israelites around the

tabernacle would have made the encampment about 12 miles square (each of the four

borders of the camp being 12 miles long).31

27James

Philip, Numbers, p. 43.

Leon Wood, A Survey of Israel's History, p. 152; and Ashley, p. 74.

29Allen, p. 715.

30John H. Sailhamer, The Pentateuch as Narrative, pp. 371-72.

31Baxter, 1:164.

28E.g.,

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

The placement and number of the Levites and firstborn of Israel ch. 3

Note the recurrence of a key word in the Pentateuch in verse l: toledot.

"For the first time after the formative events of the Exodus deliverance

and the revelation on Mount Sinai, the people of Israel are organized into a

holy people on the march under the leadership of Aaron and Moses with

the priests and Levites at the center of the camp. A whole new chapter has

opened in the life of the people of Israel, and this new beginning is marked

by the toledot formula."32

God exempted the Levites from military confrontation with Israel's enemies. He did this

because He chose the whole tribe to assist the priests, Aaron's "family" within the tribe of

Levi, in the service of the sanctuary (vv. 5-9). The Levites' "duties" were: to guard

("keep") the "holy things" (tabernacle "furnishings") from affront by (violation,

defilement from) foolish people, and to care for ("the service of") the holy things.33

"The Levites ministered to the priests (3:6) mainly in the outward

elements of the worship services, while the priests performed the

ceremonial exercises of the worship itself."34

God sanctified the Levitical service. Any Israelite who was not a Levite, who did this

work, was to suffer execution (vv. 10, 38).

On the first Passover night in Egypt God set apart "all" the "firstborn" of the Israelites

("sons of Israel"), man and beast ("from man to beast"), to Himself (vv. 12-13). He did

this when He chose Israel as His "firstborn (i.e., privileged) son." From that day to the

one this chapter records, the Israelites had to dedicate "all" their "firstborn" sons for

sanctuary service, and their "firstborn" animals (cattle, sheep, goats) as sacrifices. Now

God selected the Levites and their animals instead, to take the place of the entire nation's

"firstborn." God bestowed this privilege on the Levites because they stood with God

when the rest of the nation apostatized by worshipping the golden calf (Exod. 32:26-29).

"The power of a people lies in the birth of its progeny, and so a great value

was placed on the first child to be born—a value so great, in fact, that in

many nations the eldest son was sacrificed to the gods."35

The tabernacle responsibilities of each group were as follows:

32Olson,

Gershonites

software (curtains and coverings; vv. 21-26)

Kohathites

furniture and utensils (vv. 27-32)

Merarites

hardware (boards and bars; vv. 33-37)

p. 108.

Wenham, p. 70; Ashley, p. 69.

34Irving Jensen, Numbers: Journey to God's Rest-Land, pp. 28-29.

35Maarsingh, p. 16.

33G.

15

16

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

The total number of Levite "males" from "a month old and upward" was "22,000" (v. 39),

making it the smallest tribe in Israel by far.36 The fact that this figure does not add up

using the totals in verses 22 ("Gershon, 7,500"), 28 ("Kohath, 8,600"), and 34 ("Merari,

6,200"), may be the result of a "textual corruption,"37 in particular a "copyist's error."38

Verse 28 probably read 8,300 originally.

"3 (Hebrew sls) could quite easily have been corrupted into 6 (ss)."39

"It certainly seems that the level 22,000 is the right total, for verse 43 says

that the number of the firstborn in all the tribes was 22,273, and verse 46

says that this was 273 more than the Levite males."40

Moses then numbered all the "firstborn" males in the other tribes, from one month old

and up. There were 22,273 of them (v. 43). Evidently these were born right after the

Exodus (cf. 1:45-46). God "took" (substituted) 22,000 of the Levites in their place

(v. 45). He specified the redemption price of the remaining "273" (the superfluous,

"leftover number" of Israelite males not replaced by Levites). That is, the Israelites had to

pay "five shekels" to the priests for each of these men (vv. 46-48). This freed them from

God's claim on them for sanctuary service (cf. 1 Pet. 1:18-19).

"Theologically the section as a whole explores the theme of God's

holiness. Viewed in one way the priestly hierarchy is a means of

protecting Israel from divine holiness. The introduction of another sacred

order between priests and people emphasizes the difference between the

fallibility of man and the perfection of God. . . . Viewed in another way

the hierarchy constitutes the recognized channel through which God

brings stability and well-being to his people."41

"The Levites, the keepers of Yahweh's dwelling place, were to surround

the Tabernacle. They were particularly close, both in location and

function, because they represented the firstborn of Israel whom Yahweh

spared in the Exodus (3:12-13, 44-45; 8:5-26). It was their responsibility

to attend to the sanctuary (chap. 4) for it is ever the ministry of the eldest

son to serve his father and protect his interests."42

The number of Levites in tabernacle service ch. 4

Moses did not arrange the three Levitical families, in the text here, in the order of the

ages of their founders. He arranged them in the order of the holiness of the articles that

they managed.

36See

Merrill, "Numbers," in The Bible . . ., p. 220, for explanation of the comparatively small number of

Levites.

37G. Wenham, p. 71. Cf. A. Noordtzij, Numbers, p. 38.

38Keil and Delitzsch, 3:23. Cf. Smick, p. 117.

39G. Wenham, p. 71.

40Baxter, 1:167.

41Budd, p. 41.

42Eugene H. Merrill, "A Theology of the Pentateuch," in A Biblical Theology of the Old Testament, p. 60.

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

The Kohathites ("descendants" or "sons of Kohath")—who included Moses, Aaron, and

the priests—were in charge of the tabernacle furniture ("furnishings"), including the

"ark." God told them how to prepare the various pieces of furniture for travel, and how to

"carry" them. The priests ("Aaron and his sons") wrapped the articles of furniture, except

the laver, in various, specially prescribed "scarlet" and "blue cloths" and or "porpoise

skins," and then the other Kohathites carried them.

". . . it is to be noted that the ark was to have the blue ("violet") cloth

placed over the skins [v. 6], not under as with the other holy things (vv. 710). By such means the ark could be distinguished in the march (cf.

10:33)."43

Touching a holy piece of furniture, or even looking at one, would result in certain death

("so that they will not touch the holy objects and die . . . they shall not go in to see the

holy objects even for a moment, or they will die"; vv. 15, 20). This teaches us that even

we in New Testament times should not regard the things most closely associated with

God as common or ordinary, but give them special consideration, and deep respect. The

oils ("oil for the light" and "anointing oil"), "fragrant incense," and the flour for the daily

meal ("continual grain") "offering," were the special responsibility of Eleazar, the heir to

the high priest's office (v. 16). God also explained the responsibilities of the Gershonites

(vv. 21-28) and the Merarites (vv. 29-33).

There were "8,580" Levites who were fit for service (v. 48). A Levite had to be at least

("from") "30 years (and upward)," and not more than ("even to") "50 years old," in order

to participate in these acts of ministry (cf. 8:23-26).

"The service of God requires the best of our strength, and the prime of our

time, which cannot be better spent than to the honour of him who is the

first and best. And a man may make a good soldier much sooner than a

good minister."44

"The truth is that all work in the kingdom of God is royal service, however

unostentatious and, from the human standpoint, lowly and insignificant."45

"The sense of order and organization already observed in this book comes

to its finest point in this chapter. Again, we observe that the standard

pattern in Hebrew prose is a movement from the general to the specific,

from the broad to the particular. Chapters 1—4 follow this concept

nicely. . . . The chapters have moved from the nation as a whole to the

particular families of the one tribe that has responsibility to maintain the

symbols of Israel's worship of the Lord. Each chapter gets more specific,

more narrow in focus, with the central emphasis on the worship of the

Lord at the Tent of Meeting."46

43Smick,

p. 117.

Henry, Commentary on the Whole Bible, p. 146.

45Philip, p. 63.

46Allen, p. 731.

44Matthew

17

18

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

"The chapters [i.e., 3—4] also remind us that not everybody has the same

burdens to bear. . . . There are some burdens we can share (Gal. 6:2), but

there are other burdens that only we can bear ([Gal. 6:] v. 5)."47

A prominent emphasis in this book appears again at the end of this chapter (v. 51). Moses

carried out the Lord's commands exactly (cf. 1:54; 3:33-34; 4:42; Heb. 3:5).

2. Commands and rituals to observe in preparation for entering the

land chs. 5—9

God gave the following laws to maintain holiness in the nation, so He could continue to

dwell among His people and bless them. This was particularly important, because Israel

would soon depart from Sinai to enter the Promised Land, in which she would need to be

holy to be victorious over her enemies. These were requirements for the whole nation, not

just the priests.

"Between covenant promise and covenant possession lay a process of

rigorous journey through hostile opposition of terrain and terror. Israel had

to understand that occupation of the land could be achieved only through

much travail, for Canaan, like creation itself, was under alien dominion

and it had to be wrested away by force, by the strong arm of Yahweh, who

would fight on behalf of His people."48

Note the importance of proper interpersonal relationships in these chapters.

Holiness among the people chs. 5—6

These chapters are similar to what we read in Leviticus, in that they explain the

importance of holiness among the Israelites.

The purity of the camp 5:1-4

"The purpose of the writer is to show that at this point in the narrative,

Israel's leaders, Moses and Aaron, were following God's will and the

people were following them obediently. This theme will not continue long,

however. The narrative will soon turn a corner and begin to show that the

people quickly deviated from God's way and, with their leaders, Moses

and Aaron, failed to continue to trust in God."49

God ordered that individuals who were ceremonially unclean should not live within their

tribal communities, but should reside on the outskirts of the camp during their

uncleanness. The reason for this regulation was not any discrimination against these

people based on personal inferiority. It was the need to separate the unclean, as long as

47Wiersbe,

p. 316.

"A Theology . . .," p. 60.

49Sailhamer, p. 376.

48Merrill,

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

they were unclean, from the holy God of Israel who dwelt in the center of the camp. The

closer one lived to God, the greater was his or her need for personal holiness. In view of

the other passages that deal with lepers, people with discharges, and people who are

unclean because of a dead person (i.e., Lev. 13; 15; Num. 19), the requirement that these

people be excluded from the camp must refer to extreme cases.50

"The Rabbis had a saying which has come down to the modern Western

world via the preaching of John Wesley and Matthew Henry, 'Cleanliness

is next to godliness,' which catches this suggestion of inseparability."51

"This is the foundation principle of discipline, that the Holy One Himself

being in the camp, the camp must be holy. This principle applies to the

Church today."52

Treachery against others and God 5:5-10

To emphasize the importance of maintaining proper interpersonal relationships within the

camp, Moses repeated the law concerning the restitution of and compensation for a

trespass against one's neighbor here (cf. Lev. 5:14—6:7; Matt. 5:23-24). The expression

"sins of mankind" (v. 6) can refer either to sins committed by a human being, or to sins

committed against a human being.53 The context favors the latter option.

Added instructions covered another case. This was a person who could not fulfill his

responsibilities because the person against whom he had committed the trespass, or that

person's near kinsman, had died or did not exist. In this case, the guilty party had to make

"restitution" and compensation to the priests (v. 8).

Trespasses against one's neighbor (cf. Lev. 6:1-7) needed atonement, because they

constituted acts of "unfaithfulness" to God (v. 6). The Israelites had to maintain proper

horizontal relationships with their neighbors—in order to maintain a proper vertical

relationship with Yahweh (cf. Matt. 5:23-24).

"The point is clear—wrongs committed against God's people were

considered wrongs committed against God himself."54

"In this way, the Lord taught His people that sin is costly and hurts people,

and that true repentance demands honest restitution."55

50Smick,

p. 118.

p. 43.

52Baxter, 1:168.

53Maarsingh, p. 22.

54Sailhamer, p. 376. Cf. Ps. 51:4.

55Wiersbe, p. 318.

51Riggans,

19

20

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

The law of jealousy 5:11-31

The point of this section is: the importance of maintaining purity in the marriage

relationship in order to preserve God's blessing on Israel. Marriage is the most basic

interpersonal relationship.

In verses 11-15, the writer explained the first steps that an Israelite man who suspected

his wife of unfaithfulness should take. The offering (v. 15) was a special meal offering,

"a grain offering of memorial." Usually the grain used in the meal offering was wheat

ground into fine flour, but in this instance the man presented "barley" flour. Barley cost

only half as much as wheat (2 Kings 7:1, 16, 18). It was the food of the poor and the

cattle in the ancient Near East (Judg. 7:13; 1 Kings 5:8 [sic 4:28]; 2 Kings 4:42; Ezek.

4:12). It may have represented, ". . . the questionable repute in which the woman stood,

or the ambiguous, suspicious character of her conduct."56

The meal offering was, of course, representative of the works that an individual presented

to God. In this case, it was also an offering that the man gave in "jealousy," as a

"memorial" or remembrance. This meant that he presented it in order to bring his wife's

crime to the Lord's remembrance, so that He might judge it.

The "earthenware vessel" into which the priest poured the water from the laver was of

little value relative to the other utensils of the sanctuary. It was, therefore, an appropriate

container for this test. The "dust" he added to the water probably symbolized the curse of

sin. It is what causes humans grief as they toil for a living because of sin's curse. Another

possibility is that the dust was designed to remind the Israelites of man's humble origin

(Gen. 2:7) and his ultimate destiny: death (Ps. 22:15).57

"Since this dust has been in God's presence, it is holy. As has been said

before, one who is unclean is in great danger in the presence of the

holy."58

The release of the woman's hair, which was normally bound up, represented the

temporary loss of her glory (i.e., her good reputation). Other possibilities are that it

symbolized her openness,59 mourning,60 or uncleanness.61

Medical doctor/Bible teacher M. R. DeHaan offered a natural, as opposed to a

supernatural, explanation of what happened in this trial by ordeal, that has captured the

imagination of some evangelicals. He believed that the treated (test) water that the

woman drank, reacted to the chemical composition of the juices in her digestive system

("cause[d] bitterness"), that had become abnormal because of her guilt. Science has

56Keil

and Delitzsch, 3:31.

p. 319.

58Ashley, p. 129.

59Allen, p. 746.

60Merrill, "Numbers," in The Old . . ., p. 107.

61Ashley, p. 129.

57Wiersbe,

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

established that certain emotions and nervous disturbances change the chemical

composition of our bodily secretions. While this might be what produced the symptoms

described in the text, DeHaan erred, I believe, in interpreting the "dust" (v. 17) that the

priest mixed with the water as a "bitter herb."

"We believe that, if we knew the identity of the bitter herb which Moses

used, the same test would work today."62

The physical symptoms of God's judgment on the woman, if she was guilty (vv. 23, 27),

point to a special affliction—rather than one of the natural diseases that overtook the

Israelites. Josephus said it was ordinary dropsy.63 This seems unlikely, in view of how

Moses described her condition. Merrill believed her sense of guilt produced a

psychosomatic reaction.64 Noordtzij concluded that the woman's pregnancy resulted in a

miscarriage because the bitter water destroyed the fetus.65 It is interesting, whatever the

cause, that the punishment fell on the very organs that had been the instruments of the

woman's sin.

"The thigh is often used as a euphemism for the sexual organs."66

"The most probable explanation for the phrase ['and make your abdomen

swell and your thigh waste away'] . . . is that the woman suffers a collapse

of the sexual organs known as a prolapsed uterus. In this condition, which

may occur after multiple pregnancies, the pelvis floor (weakened by the

pregnancies) collapses, and the uterus literally falls down. It may lodge in

the vagina, or it may actually fall out of the body through the vagina. If it

does so, it becomes edematous and swells up like a balloon. Conception

becomes impossible, and the woman's procreative life has effectively

ended . . ."67

Apparently the translators of the New Revised Standard Version took the view described

above, since they rendered the phrase in question: "when the LORD makes your womb

discharge . . . your uterus drop!" (vv. 21-22, et al.).

62M.

R. DeHaan, The Chemistry of the Blood and Other Stirring Messages, p. 48.

Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 3:11:6. Josephus was not a divinely inspired historian, but his

history is generally reliable.

64Merrill, "Numbers," The Bible . . ., p. 222; and idem, "Numbers," in The Old . . ., p. 107.

65Noordtzij, p. 57. Cf. Smick, p. 120; The Nelson Study Bible, p. 237.

66Riggans, p. 50. Cf. Gen. 24:2, 9; 47:29.

67Tikva Frymer-Kensky, "The Strange Case of the Suspected Sotah (Numbers V 11-31)," Vetus

Testamentum 34:1 (January 1984):20-21. See also the same author's more popularly written article, "The

Trial Before God of an Accused Adultress," Bible Review 2:3 (Fall 1986):46-49, which, by the way,

provides supporting evidence for the widespread prohibition of polygamy in the ancient Near East. Other

helpful resources are Michael Fishbane, "Accusations of Adultery: A Study of Law and Scribal Practice in

Numbers 5:11-31," Hebrew Union College Annual 45 (1974):25-45; Herbert Chanan Brichto, "The Case of

the Sota and a Reconsideration of Biblical 'Law,'" Hebrew Union College Annual 46 (1975):55-70; W.

McKane, "Poison, Trial by Ordeal and the Cup of Wrath," Vetus Testamentum 30:4 (October 1980):474-92;

and Ashley, pp. 132-33.

63Flavius

21

22

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

Verses 23-28 explain additional acts that were to take place before the woman drank the

water. They are not in chronological sequence with verses 16-22. Drinking the water was

the last step in the ritual, which took place in the tabernacle courtyard.

"The thought expressed here is that that which is written is dissolved in the

water and imparts to the water the power inherent in the words so that the

water can accomplish that of which the words speak (we must remember

that to Israel and the ancient Near Eastern world words were more than

sounds; they had power)."68

"The ritual trial of the Sotah [suspected adulteress] ended with the

drinking of the potion. Nothing further was done, and we can assume that

the woman went home to await the results at some future time."69

The man whom Moses referred to in verse 31 is "the man" who accused his wife of

unfaithfulness. He incurred no guilt before God for being jealous of his wife's fidelity.

This case raises some questions: Why was only the woman punished if she had been

unfaithful? The answer seems to be that her male companion in sin was unknown. If she

was proven to be unfaithful, and the adulterer was identifiable, both partners should have

suffered death by stoning (Lev. 20:10).

What about a wife who suspected that her husband had been unfaithful to her? Did she

not have the same recourse as the husband? Evidently she did not. The Israelites were to

observe God's revealed line of authority consistently. A man was directly responsible to

God, but a woman was directly responsible to her father (if unmarried) or her husband (if

married). Thus a wife was responsible to her husband in a way that the husband was not

responsible to his wife. This does not mean that marital infidelity was a worse sin for a

wife than it was for a husband. It simply explains how God wanted the Israelites to

handle infidelity in the case of a wife. Perhaps God Himself retained the responsibility

for judging a husband who was unfaithful to his wife (cf. Heb. 13:4).

This procedure protected the wife of an extremely jealous husband, who might otherwise

continue to accuse her. He would suffer shame by her proven innocence, and public

embarrassment, since this was a public ceremony.

"This legislation forbids human punishment of a woman on the basis of

suspicion alone, and, in fact, protects her from what could be a death

sentence at the hands of the community."70

"Marital deceit is a matter of such seriousness that the truth must be

discovered. It is harmful to the sanctity of the community at large, and

destructive of one of the bases of community life."71

68Noordtzij,

p. 56.

69Frymer-Kensky,

70Ashley,

p. 135.

71Budd, p. 66.

"The Strange . . .," p. 22.

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

". . . this particular case law is included here because it gives another

illustration of God's personal involvement in the restitution for the sin of

the nation. Within God's covenant with Israel, there could be no hidden sin

among God's people nor any hidden suspicion of sin.

"The law of jealousy shows that through the role of the priest, God was

actively at work in the nation and that no sin of any sort could be tolerated

among God's holy people."72

Maintaining purity in marriage is likewise essential to assure God's blessing in the church

(cf. 1 Pet. 3:7; Heb. 13:4).

The Nazirite vow 6:1-21

"After the law for the discovery and shame of those that by sin had made

themselves vile [in 5:11-31], there follows this for the direction and

encouragement of those who by their eminent piety and devotion had

made themselves honourable."73

The emphasis in this section continues to be on the importance of maintaining purity in

the camp, so that God's blessing on Israel might continue unabated.

The "Nazirite" (from the Hebrew root nazar, meaning "to separate") illustrated the

consecrated character of all the Israelites, and of the nation as a whole, in an especially

visible way.

The Nazirite "vow of separation" was normally temporary. There are two biblical

examples of life-long Nazirites: Samson and Samuel. John the Baptist may have been a

third case, but we do not know for sure that he lived as a Nazirite before he began his

public ministry. This "vow of separation" was also normally voluntary. Any male or

female could take this vow, that involved dedication to God's service. The vow itself

required three commitments. These were not the vow itself, but grew out of it as

consequences:

1.

The separated one abstained from any and all fruits of the "grape vine" (v. 4).

Perhaps God commanded this because: ". . . its fruit was regarded as the sum and

substance of all sensual enjoyment."74 Other passages link strong drink (wine or

hard liquor) with the neglect of God's law (e.g., Gen. 9:20-27; 19:32-38; Prov.

31:4-6; Hab. 2:5).

"In itself, wine culture was considered to be good—Israelites regarded the

harvest of their vineyards as a blessing—but there was also a dangerous

side to it: the possibility of lapsing into a pagan lifestyle."75

72Sailhamer,

p. 377.

p. 147.

74Keil and Delitzsch, 3:35. Cf. Riggans, p. 53.

75Maarsingh, pp. 25-26.

73Henry,

23

24

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2.

2016 Edition

The Nazirite was required to leave his or her hair uncut ("no razor shall pass over

his head . . . he shall let the locks of hair on his head grow long"; v. 5). The

significance of this restriction has had many interpretations by the commentators,

as have the other restrictions. The most probable explanation, I believe, connects

with the fact that hair represented the strength and vitality of the individual (cf.

Judg. 16:17; 2 Sam. 14:25-26).76 The long hair of the Nazirite would have

symbolized the dedication of the Nazirite's strength and vigor to God.

"There might also have been a negative reason [for] this prescription. In

many nations at this time, people devoted their hair to their gods."77

"Hair is representative of life itself, for only a living man produces hair.

He offered it, therefore, in place of his own body, as a sign that he himself

was a 'living sacrifice, holy and well-pleasing to God.'"78

3.

The third commitment was to avoid any physical contact with a human corpse

("do not go near to a dead person"). This is perhaps the easiest restriction to

explain. It seems that since the Nazirite had dedicated himself to a period of

separation to God, and from sin, he should avoid contact with the product of sin,

namely, death. Perhaps, too, since death was an abnormal condition, contact with

dead bodies caused defilement.

If the Nazirite broke his vow through no fault of his own, he had to follow the prescribed

ritual for cleansing, and then begin the period of his vow again (vv. 9-12).

". . . there was the recognition that some things in life superseded the

requirements of the vow. If someone died suddenly in one's presence, for

example, the vow could be temporarily suspended (v. 9). After the

emergency had passed, there were provisions for completing the vow (vv.

10-12ff)."79

The Nazirite did not withdraw from society, except in the particulars of these restrictions.

He lived an active life of service in Israel. His dedication to God did not remove him

from society, but affected his motivation and activities as he lived.

The Nazirite lived as a priest temporarily, in the sense that he lived under more stringent

laws of holiness, and served God more directly than other Israelites did. His service was

not generally the same as the priests', but sometimes it involved some sanctuary service,

as well as other types of service (e.g., Samuel).

"This law specifically shows that there were provisions not just for the

priest but for all members of God's people to commit themselves wholly to

God. Complete holiness was not the sole prerogative of the priesthood or

76Cf.

Ashley, p. 143.

p. 26.

78Smick, p. 120.

79Sailhamer, pp. 377-78.

77Maarsingh,

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

the Levites. The Nazirite vow shows that even laypersons, men and

women in everyday walks of life, could enter into a state of complete

devotion to God. Thus this segment of text teaches that any person in

God's nation could be totally committed to holiness."80

When the time of the Nazirite's vow expired, he had to go through a prescribed ritual

called "the law of the Nazirite" (vv. 13, 21). Burning his cut hair on the brazen altar

under his peace offering (v. 18) probably symbolized giving (dedicating) to God the

strength and vigor that he had previously employed in His service. It also ensured that no

one would misuse his hair, possibly in a pagan ritual. The Nazirite ate part of his "vow

fulfillment offering" (v. 19). He thus physically enjoyed part of the fruits of his

dedication to God.

"Nobody is saved by making and keeping a vow. Salvation is a gift of God

to those who believe, not a reward to those who behave."81

God did not require the taking of vows under the Mosaic Law (cf. Lev. 27). Consequently

the fact that Paul took a Nazirite vow (Acts 18:18), and paid the expenses of others who

had taken one (Acts 21:26), does not indicate that he was living under the Law of Moses.

He was simply practicing a Jewish custom, that had prevailed into the Church Age, as the

Mosaic Law regulated that custom. He did this to win Jews to Jesus Christ, not because

as a Christian Jew he was under the Mosaic Law (1 Cor. 9:19-23)—he was not.

"It can hardly be denied that there is a desperate need in the church today

for such leadership, for men utterly given over to God for His purposes—

not men of fanatical zeal (which can very often be fleshly and even

devilish), but men of controlled fire, men who can truly say, 'One thing I

do' (Phil. 3:13), men of whom it can be said that the love of Christ

constrains them, giving their lives depth, drive, and direction in the service

of God."82

Though Jesus was not a Nazirite, He exemplified what those dedicated to God should

look like in their behavior, regardless of when they happen to live.

Remember, Christians are not under the Mosaic Law (Mark 7:18-19; Acts 10:12-15;

15:19-20; Rom. 7:1-4; 10:4; 14:17; 1 Cor. 8:8; Gal. 3:24; 4:9-11; Col. 2:16-17; Heb.

7:12; 9:8-12). Some well-meaning Christian teachers, throughout the centuries, have been

confusing many believers, by encouraging them to submit to certain regulations that are

unique to the Mosaic Law. This is legalism. If someone chooses not to eat pork, for

example, for health reasons, that is entirely up to him or her. But if that person thinks that

he or she will be more pleasing to God by not doing so, they are mistaken (cf. Acts 10; 1

Tim. 4:1-5). There is more personal freedom under the New Covenant than there was

under the Old.

80Ibid.,

p. 377.

p. 320.

82Philip, pp. 86-87.

81Wiersbe,

25

26

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

The Aaronic benediction 6:22-27

The location of this benediction in this context indicates that one of the priest's central

tasks was to be a source of blessing for God's people. This blessing, like the preceding

Nazirite legislation, deals with the purification of Israel. As the nation prepared to move

out toward the Promised Land, God gave this benediction to the priests to offer for the

sanctification of the people. God's will was to bless all His people, not just the Nazirites.

The priests were the mediators of this blessing from God to the Israelites.

"Whereas Nazirites generally undertook their vows for a short period, the

priests were always there pronouncing this blessing at the close of the

daily morning service in the temple and later in the synagogues."83

This blessing was threefold, and each segment contained two parts. In each line of poetry,

the second part was a particular application of the general request stated in the first part.

The first part hoped for God's action, that would result in the people's benefit in the

second part. The three blessings were increasingly emphatic. Even the structure of the

blessing in Hebrew is artful. Line one consists of 15 letters (3 words), line two of 20

letters (5 words), and line three of 25 letters (7 words).

"Each of the three clauses, in a different way, gives expression to God's

commitment to Israel—a commitment which promises earthly security,

prosperity, and general well-being."84

The first blessing is the most general ("The LORD bless you, and keep you"; v. 24). God's

"blessing" is His goodness poured out. The priest called on Him not only to provide for

His people, but to defend ("keep," guard) them from all evil (cf. Matt. 6:13).

The second blessing is more specific ("The LORD make His face shine on you, and be

gracious to you"; v. 25). God's "face" is the revelation of His personality (i.e., Himself) to

people. It radiates as fire does, consuming evil and bestowing light and warmth, and it

shines as the sun, promoting life. God's graciousness refers to the manifestation of His

favor and grace in the events of life.

The third blessing is the most specific ("The LORD lift up His countenance on you, and

give you peace"; v. 26). "Lifting up the countenance" refers to manifesting power. The

priests, in pronouncing this blessing, would be calling on God to manifest His "power"

for His people. Specifically, this would produce "peace" (Heb. shalom). "Shalom" does

not mean simply the absence of aggravation; it is the sum of all God's blessings.

"The two main elements in the oracle are 'grace and peace.' It is probable

that the Apostle Paul based his salutations on this oracle."85

83G.

Wenham, p. 89.

p. 77.

85The NET Bible note on 6:22.

84Budd,

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

"Excavations of a tomb overlooking the Hinnom Valley in Jerusalem

[Ketef Hinnom, 1979] brought to light a small silver scroll containing a

tiny inscription bearing the words of the priestly benediction of Numbers

6:24-26. This sheds light on Hebrew orthography and morphology. Also

its date (ca. seventh century B.C.) long precedes the composition of the P

document of historical-critical scholarship (450 B.C.), thus undermining

the hypothesis to that degree."86

One writer suggested the following alternative translation of verse 27:

"And when they shall name me the Most High of the Israelites, I, on my

part, will bless them."87

This rendering seems to capture the spirit of God's promise in this benediction. This

blessing has always been a very important part of Israel's worship, even to the present

day, in Judaism.

"This was a type of Christ's errand into the world, which was to bless us

(Acts iii. 26), as the high priest of our profession."88

". . . the high priestly blessing was pronounced whenever the nation of

Israel gathered for collective worship and sacrifice as well as when the

individual Israelite brought sacrifices to the LORD. The nature of the

blessing was that of an oracle, a sure word from God that He had accepted

the sacrifice and was pleased with the worshipper. The contents of the

blessing were protection, gracious dealings, and peace with God, which

assuredly produced the effect of joy, security, and confidence on the part

of the people."89

"Some people suggest that only spontaneous prayer is 'real' prayer; verses such as

these show that such sentiment is not correct."90

". . . the Aaronic blessing concludes the section of text dealing with the bulk of

Israel's priestly legislation, and, implicitly, promises that if these laws are kept,

the blessing of God will follow. The material in this major section (Lev. 1—

Num. 6) comes between the date of the erection of the tabernacle and the

movement of the camp some fifty days later (Num. 10:11)."91

86Eugene

Merrill, "The Veracity of the Word: A Summary of Major Archaeological Finds," Kindred Spirit

34:3 (Winter 2010):13.

87Pieter de Boer, "Numbers vi 27," Vetus Testamentum 32:1 (January 1982):13.

88Henry, p. 148.

89Neil W. Arnold, "The High Priestly Blessing," Exegesis and Exposition 2:1 (Summer 1987):50. See also

"The Priestly Blessing," Buried History 18:2 (June 1982):27-30. For other instances of the use of this

blessing, see Michael Fishbane, "Form and Reformulation of the Biblical Priestly Blessing," Journal of the

American Oriental Society 103:1 (January-March 1983):115-21; and Leon Liebreich, "The Songs of

Ascents and the Priestly Blessing," Journal of Biblical Literature 74 (1955):33-36.

90Allen, p. 754.

91Ashley, pp. 149-50.

27

28

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

2016 Edition

The dedication of the tabernacle chs. 7—9

The revelation of ordinances and instructions designed to enhance the spiritual

sanctification of the Israelites as they journeyed to the Promised Land ends with

chapter 6. The narrative of events that transpired just before the nation began marching

resumes with chapter 7. Chronologically, chapters 7—9 precede chapters 1—6.

The offerings at the dedication ch. 7

The "presentation" this chapter records—an elaborate ceremony of dedicatory offerings

lasting 12 days—jumps back chronologically, and took place at the time when the

Israelites dedicated the tabernacle and the brazen altar (vv. 1-2; cf. Lev. 8:10).

"The purpose of this section of narrative is to show that as the people had

been generous in giving to the construction of the tabernacle (Ex 35:4-29),

now they showed the same generosity in its dedication."92

First, the 12 Israelite tribes presented as a contribution gift "six wagons (covered carts)"

and "12 oxen" to the Merarite and Gershonite Levites, to use in their service of carrying

the materials of the tabernacle (vv. 1-9). Of the six wagons, the Gershonites received two

wagons and the Merarites four. The Kohathites needed no wagons, since they carried the

sanctuary furniture with poles on their shoulders (cf. 2 Sam. 6:3, 7-8).

"Observe here, How [sic] God wisely and graciously ordered the most

strength to those that had the most work."93

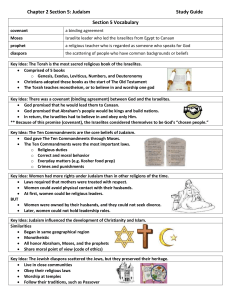

Day in second year94

Day 1, first month

Day 8, first month

Day 12, first month

Day 14, first month

Day 1, second month

Day 14, second month

Day 20, second month

92Sailhamer,

Event

Completion of tabernacle

Laws for offerings begin

Offerings for altar begin

Ordination of priests begins

Ordination of priests completed

Offerings for altar completed

Appointment of Levites

Second Passover

Census begins

Passover for those unclean

The cloud moves, the camp begins

its trek

p. 379.

p. 148.

94Allen, p. 757, after G. Wenham, p. 91.

93Henry,

Text

Exod. 40:2; Num. 7:1

Lev. 1:1

Num. 7:3

Lev. 8:1

Lev. 9:1

Num. 7:78

Num. 8:5

Num. 9:2

Num. 1:1

Num. 9:11

Num. 10:11

2016 Edition

Dr. Constable's Notes on Numbers

This long section—this chapter is the second longest in the Bible—records the

presentation of gifts for the altar (v. 10) by each tribal prince (vv. 12-88). The longest

chapter in the Bible is Psalm 119. The Israelites spread the presentation out over 12 days,

one per day, because it took a whole day to receive and sacrifice what each tribe

presented.

Each tribe offered exactly the same gifts. "one silver dish" and "one silver bowl," each

"full of fine flour mixed with oil," "one gold pan full of incense," a year-old "bull,"

"ram," and "male lamb" ("for a burnt offering"), a "male goat" ("for a sin offering"), "two

oxen," "five rams," "five male goats," "five male lambs" (for "peace offerings") No tribe

was superior or inferior to the others in this respect. Each had equal privilege and

responsibility before God to worship and serve Him.

Moses faithfully recorded the presentation of each gift, even though the record is