Context-Dependent Learning with Unfamiliar Music in an Online

advertisement

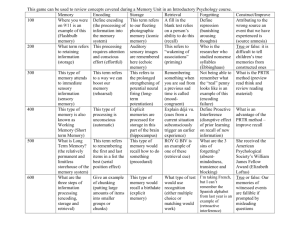

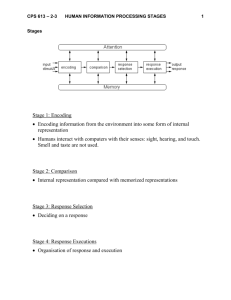

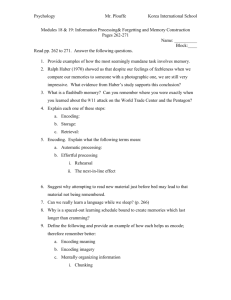

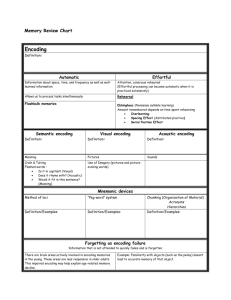

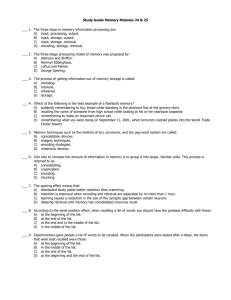

Context‐Dependent Learning with Unfamiliar Music in an Online Setting Emmanuel Brian Dizon & David R. Gerkens California State University, Fullerton Introduction Method Test with Music •Godden and Baddeley (1975) used the two natural environments, on land and underwater as context to investigate encoding specificity. Participants learned the words either on land or underwater and they later recalled the words either on land or underwater. They recalled more words when the context of encoding and retrieval processes matched (i.e., land‐land, underwater‐underwater). •Smith (1985) used music as context. Participants learned words while listening to Mozart piano music, jazz music, or no music. They recalled the words either with similar music context (i.e., piano‐piano) or different music context (i.e., piano‐jazz). The encoding specificity effect was found in similar music context but it was not found in same cue quiet context (no music‐no music). Smith concluded that background music can induce context‐dependent memory and it creates a facilitative effect, which means memory is better when learning and retrieval processes are accompanied with a similar additional context cue. •Grant et al. (1998) found context‐dependent memory when participants remembered more information when they read an article and were tested with matching context for both silent and noisy conditions (i.e., silent study/silent test, noisy study/noisy test). •The present study assesses the nature of encoding specificity in an online setting with the use of unfamiliar music. To the authors’ knowledge, no published context‐dependent experiments were not conducted online. Also, they believed that familiar music can affect the data because a music that is familiar to one individual may not be familiar to another individual. •Grant et al. (1998) mentioned that students have more control their study environment (i.e., with background music, background noise or a quiet environment) but not the test environment. Test environments are typically quiet. The current study wanted to explore the more ecologically valid circumstance of people studying on a computer at home. Hypotheses Test with No Music 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 •Encoding specificity is the theory that memory is more effective when the cues present during the encoding phase are also available during the retrieval phase (Tulving & Thompson, 1973). Figure 2: Learning Phase Sample Learning with Music Learning with No Music Learning with Music Online Learning with No Music Lab Figure 4: Encoding Specificity Effects in Online and Lab Settings Discussion •The first hypothesis was not supported. The interaction of learning phase x testing phase was not significant for either the online or lab settings. However, the means were in the correct pattern for an encoding specificity effect. In learning with music for both the lab and online settings, means were numerically higher when they were tested with music but the difference was not significant. Figure 1: Details of Experimental Procedure Participants •385 undergraduate students from California State University, Fullerton, participated in the experiment for partial fulfillment of the course research requirement. •33 participants were excluded from the analysis. • 11 participants (from the lab group) who were distracted by loud noise from construction below the lab. • 22 participants who said "Yes" to the question "Have you heard the music before?" •263 participants volunteered for the online group (experimental group) and 89 participants volunteered for the laboratory group (comparison group). Materials & Procedure •Participants learned 2 different word lists containing 15 unrelated words. The music context of each list did not change. Each word was presented for 2 seconds. •Hypothesis 1: The similar music context condition (music‐music, No music‐no music) was predicted to produce more words recalled than the different music context (music‐no music, no music‐music). •The counterbalance condition changed the order of the test condition. •Hypothesis 2: Participants in no music‐no music contexts were predicted to recall fewer words than participants in music‐music conditions. •Participants were also given a brief yes/no questionnaire. If they said “yes” to the following questionnaires “Do you know the name of the song?” and “Have you heard the music before? •Hypothesis 3: The online group and laboratory group were predicted to show a similar pattern of recall (i.e., no effects involving place are expected). •Online Experimental Website (See Figure 2 and Figure 3) •Participants were given two minutes to recall words on each test. •Music: Honestly – Startle the Heavens. Figure 3: Testing Phase Sample Results •A 2 (learning phase)x 2 (counterbalance) x 2 (testing phase) x 2 (place) mixed ANOVA was conducted. All factors were between‐ subjects except testing phase, which was a repeated measure. •A significant interaction was found in learning phase x place , F (1, 344) = 6.041, MSE = 7.895 , p = .014, η2 = .017. •There was a marginally significant interaction of learning phase x place x CB, F (1, 344) = 3.599, MSE = 7.895, p = .059, η2 = .010. •Follow‐up analyses looked at the learning phase x CB interaction in the lab and online groups separately. •In the online setting, there was a significant interaction of learning phase x CB, F (1, 259) = 5.727, p = .017, η2 = .022. In learning with no music, participants in Counterbalance A (test with music first; M = 7.895, SE = .265) scored better than participants in Counterbalance B (test without music first; M = 6.892, SE = .292). Counterbalances did not significantly differ in the learn with music condition. •In the lab setting, there was a significant main effect of learning phase, F (1, 85) = 5.467, MSE = 5.440 , p = .022, η2 = .060. Participants in the learning with music condition (M = 7.757, SE = .260) recalled more words than participants in learning with no music condition (M = 6.915, SE = .249). •The second hypothesis was supported because there was a significant main effect of Learning phase in the lab setting. Participants who encoded with no music recalled fewer words than participants who encoded with music. •The third hypothesis was not supported because significant effects were found involving the place variable. There was a different pattern of recall for online and lab settings. Results from the lab were consistent with Smith (1985) in that the addition of music as a cue during encoding improved recall. • It is difficult to explain the counterbalance x learning interaction in the online condition. Perhaps the introduction of music during the first test captured the attention of participants in what may have been a distracting environment. •Future studies might use more memorable words or a deep processing task to improve recall generally. More upbeat or familiar music may also have a stronger effect than the ambient style music used in the current experiment. References Godden, D., & Baddeley, A. (1975). Context‐dependent memory in two natural environments: On land and underwater. British Journal of Psychology, 66(3), 325‐331 Grant, H. M., Bredahl, L. C., Clay, J., Ferrie, J., Groves, J. E., McDorman, T. A., & Dark, V. J. (1998). Context‐dependent memory for meaningful material: Information for students. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 12(6), 617‐623. Smith, S. M. (1985). Background music and context‐dependent memory. The American Journal of Psychology, 9(4), 591‐603. Tulving, E., Thomson, D.M. (1973). Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychological Review, 80(5), 352‐373.