Mini-Lesson: Conflict in the Cabinet

advertisement

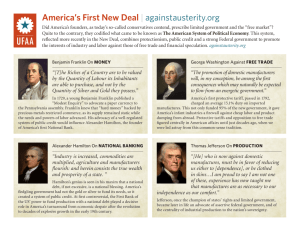

Mini-Lesson: Conflict in the Cabinet - Hamilton vs. Jefferson AP U.S. History 75 minutes 1) Bell Ringer (5 min) Project the prompt. Cue the video clip 2) Debrief the Bell Ringer (3 min) Get a few responses for each prompt Fill in any gaps 3) Scaffold and watch the Clip "Hamilton Takes Jefferson to School" (7 min) "To give context to what we are studying, we are going to watch a clip from the HBO mini-series John Adams, which is based on the book (show them) by author David McCullough. What do I mean by giving context?" http://www.voutube.com/watch?v=notJuFGXQ.9w&feature=related Set up the clip (setting, characters, circumstances) o Spring 1790 - Cabinet meeting in NYC, the President's residence and current capital o Jefferson has just returned from a long stay in France o Adams, as VP, is in the room as well. o Pay close attention to Washington's body language. o See if you can tell whose side VP Adams favors? 4) Debrief the Clip (3 min) o What did you see, notice? Especially with respect to Washington o Can we say anything about Hamilton's and Jefferson's personalities? o How might their conflict affect President Washington's ability to do his job? o "As you can imagine, it was quite difficult for Washington to handle the conflict between Hamilton and Jefferson. After all, he was a military man first and a politician second. Furthermore, he did not possess equivalent expertise in matters of law, finance, diplomacy, business, philosophy, etc. that his cabinet members (Hamilton and Jefferson) did. He needed these men to be at their best in order for him to be an effective President while the republic was so new and fragile. Clearly, he was frustrated by the factions forming within his own cabinet. What were the two factions?" 5) Secondary Source Review: Pearson piece (12 min) o Distribute handout o Project handout o Describe handout o Read handout aloud and ask questions throughout o Collect handout 6) Primary Source Review: Paired Reading/Jigsaw - GW, AH & TJ Correspondence (20 min) • "Approximately two years following the film clip, George Washington exchanged letters with Hamilton & Jefferson in which references were made about the conflict between them. [Project the AH & TJ letters] We're going to examine these primary documents and complete a graphic organizer worksheet" i. [Project the graphic organizer], distribute it, review it, and ask if there are questions. ii. Students get out of their desks, come to the middle of the room, and choose a partner. In pairs, they line up next to each other, with half on one side of the room and half on the other side. iii. Teacher assigns numbers one and two to each respective side. "Ones" get GW & AH letters, "Twos" get GW & TJ letters. WRITE YOUR NUMBER AT THE TOP OF YOUR WORKSHEET. Teacher passes letter sets out to pairs. Teacher suggests that the stronger reader take the role of GW. Each pair must decide on roles. iv. Teacher tells students to face each other and read aloud to each other. Students can sit or stand anywhere they would like. v. Following reading to each other, each pair works on its respective side of the graphic organizer, completing items 1-3. DO NOT WORK ON THE ITEM AT THE BOTTOM YET. Teacher encourages students to ask questions if needed during this phase. Teacher asks student pairs to return to their respective assigned seats when they are finished with items 1-3. vi. [Project letters] • Jigsaw (10 min) o In order to complete the other side of the worksheet, each student must find a new partner with an opposite number. GET UP AND MOVE AROUND. o Pairs must report to one another and complete the other side of their respective graphic organizers. o Teacher asks student pairs to return to their respective assigned seats once the graphic organizer is complete. 7) Debrief the Primary Source Review Activity (12 min) o Elicit a variety of responses o Probe for consensus, disagreement o Ask students to use evidence to support their responses 8) Homework Assessment- Entry Ticket (3 min)* o As a homework assignment and entry ticket to the next class, students must respond to the prompt at the bottom of the worksheet. o We will share responses at the beginning of the next class. *An alternative or additional assessment would be to do Percocco's "Historical Heads", with Hamilton and Jefferson as opposing historical heads. To do this effectively, we'd need to develop the characters with more authentic biographical information using multimedia and primary and secondary source material. Conflict in the Cabinet, 1792 Prior Knowledge On your own, please write down at least one thing you know about: •Thomas Jefferson's political affiliation and beliefs •Alexander Hamilton's political affiliation and beliefs •The relationship between both men You have five minutes. It is Spring 1790. The cabinet meets for the first time in New York City at the President's residence. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton is at the peak of his power. Secretary of State Jefferson has just returned from a long stay in France. Vice President Adams is in the room. Pay close attention to President Washington's body language. See if you can tell whose side (Hamilton's or Jefferson's) Adams favors? Washington? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=notJuFGXQ9w&feature=related Essential Question: How did the debate between Jefferson and Hamilton help shape the political system of the United States? By Ellen Holmes Pearson, Associate Professor of History, University of North Carolina - Asheville In George Washington's Farewell Address (1796), the retiring president warned that the creation of political factions, "sharpened by the spirit of revenge/' would most certainly lead to "formal and permanent despotism." Despite Washington's cautionary words, two of his closest advisors, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, helped to form the factions that led to the dual party system under which the U.S. operates today. Other men, most notably James Madison and John Adams, also contributed to the formation of political parties, but Hamilton and Jefferson came to represent the divisions that shaped the early national political landscape. Although both men had been active in the Revolutionary effort and in the founding of the United States, Jefferson and Hamilton did not work together until Washington appointed Jefferson the first secretary of State and Hamilton the first secretary of the Treasury. From the beginning, the two men harbored opposing visions of the nation's path. Jefferson believed that America's success lay in its agrarian tradition. Hamilton's economic plan hinged on the promotion of manufactures and commerce. While Hamilton distrusted popular will and believed that the federal government should wield considerable power in order to steer a successful course, Jefferson placed his trust in the people as governors. Perhaps because of their differences of opinion, Washington made these men his closest advisors. Hamilton's economic plan for the nation included establishing a national bank like that in England to maintain public credit; consolidating the states' debts under the federal government; and enacting protective tariffs and government subsidies to encourage American manufactures. All of these measures strengthened the federal government's power at the expense of the states. Jefferson and his political allies opposed these reforms. Francophile Jefferson feared that the Bank of the United States represented too much English influence, and he argued that the Constitution did not give Congress the power to establish a bank. He did not believe that promoting manufactures was as important as supporting the alreadyestablished agrarian base. Jefferson deemed "those who labour in the earth" the "chosen people of God . . . whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue." He advised his countrymen to "let our work-shops remain in Europe." When George Washington's administration began, the two camps that formed during the Constitutional ratification debates - those groups known as the Federalists and Anti-Federalists - had not yet solidified into parties. But, disagreements over the nation's direction were already eroding any hope of political unity. In May of 1792, Jefferson expressed his fear to Washington about Hamilton's policies, calling Hamilton's allies in Congress a "corrupt squadron." He expressed fear that Hamilton wished to move away from the Constitution's republican structure, toward a monarchy modeled after the English constitution. That same month, Hamilton confided to a friend that "Mr. Madison cooperating with Mr. Jefferson is at the head of a faction decidedly hostile to me and my administration, and . . . dangerous to the union, peace and happiness of the Country." By the time Jefferson and John Adams vied for the presidency in 1796, political factions had formed under the labels "Republicans" and "Federalists." In fact, by 1804 the advent of political parties necessitated a constitutional amendment that changed the electoral process to allow president/vice president tickets on the ballot. The Federalists dominated the national government through the end of the 18th century. Despite President Washington's efforts at unity, political differences proved to be too deep to promote consensus. The Republican Party emerged as organized opposition to Federalist policies, and despite Jefferson's assurances in his first inaugural address that Americans were "all republicans" and "all federalists," faction had solidified into party. SOT-- * n ^ i •?. * ^ <l*s' A, ,v '« s * ;v ? - v! *v« t ^ , 'Si ^rf> :C « ^ V ^ ! , V • \< * George Washington to Alexander Hamilton, August 26,1792 (Private) Mount Vernon, August 26,1792. My dear Sir: Differences in political opinions are as unavoidable as, to a certain point, they may, perhaps, be necessary; but it is exceedingly to be regretted that subjects cannot be discussed with temper on the one hand, or decisions submitted to without having the motives which led to them improperly implicated on the other: and this regret borders on chagrin when we find that men of abilities, zealous patriots, having the same general objects in view, and the same upright intentions to prosecute them, will not exercise more charity in deciding on the opinions and actions of one another. When matters get to such lengths, the natural inference is, that both sides have strained the Cords beyond their bearing, and, that a middle course would be found the best, until experience shall have decided on the right way, or, which is not to be expected, because it is denied to mortals, there shall be some infallible rule by which we could fore-judge events. Having premised these things, I would fain hope that liberal allowances will be made for the political opinions of each other; and instead of those wounding suspicions, and irritating charges, with which some of our Gazettes are so strongly impregnated, and cannot fail if persevered in, of pushing matters to extremity, and thereby to tear the Machine asunder, that there might be mutual forbearances and temporizing yields on all sides. Without these I do not see how the Reins of government are to be managed, or how the Union of the States can be much longer preserved. How unfortunate would it be if a fabric so goodly, erected under so many Providential circumstances, and in its first stages, having acquired such respectability, should from diversity of sentiments or internal obstructions to some of the acts of Government (for I cannot prevail on myself to believe that these measures are as yet the deliberate acts of a determined party) should be harrowing our vitals in such a manner as to have brought us to the verge of dissolution. Melancholy thought! But one at the same time that it shows the consequences of diversified opinions, when pushed with too much tenacity, it exhibits evidence also of the necessity of accommodation, and of the propriety of adopting such healing measures as may restore harmony to the discordant members of the Union, and the Governing powers of it. I do not mean to apply this advice to any measures which are passed or to any particular character; I have given it in the same general terms to other Officers of the Government. My earnest wish is, that balsam may be poured into all the wounds which have been given, to prevent them from gangrening and from those fatal consequences which the community may sustain if it is with held. The friends of the Union must wish this; those who are not, but wish to see it ended, will be disappointed, and all things I hope will go well. Affectionate regards of yours, &c. George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, August 23,1792 (Private) Mount Vernon, August 23, 1792. /,.,» My dear Sir: How unfortunate, and how much is it to be regretted, that whilst we are encompassed on all sides with avowed enemies and insidious friends [reference to Native Americans and Spaniards], that internal dissensions should be harrowing and tearing our vitals. The last, to me, is the most serious, the most alarming, and the most afflicting of the two. And without more charity for the opinions and acts of one another in Governmental matters, or some more infallible criterion by which the truth of speculative opinions, before they have undergone the test of experience, are to be forejudged than has yet fallen to the lot of fallibility, I believe it will be difficult, if not impracticable, to manage the Reins of Government or to keep the parts of it together: for if, instead of laying our shoulders to the machine after measures are decided on, one pulls this way and another that, before the utility of the thing is fairly tried, it must, inevitably, be torn asunder. And, in my opinion the fairest prospect of happiness and prosperity that ever was presented to man, will be lost, perhaps forever! My earnest wish, and my fondest hope therefore is, that instead of wounding suspicions, and irritable charges, there may be liberal allowances, mutual forbearances, and temporizing yields on all sides. Under the exercise of these, matters will go on smoothly, and, if possible, more prosperously. Without them everything must rub; the Wheels of Government will clog; our enemies will triumph, and by throwing their weight into the disaffected Scale, may accomplish the ruin of the goodly fabric we have been erecting. I do not mean to apply these observations, or this advice to any particular person, or character. I have given them in the same general terms to other Officers of the Government; because the disagreements which have arisen from difference of opinions, and the Attacks which have been made upon almost all the measures of government, and most of its Executive Officers, have, for a long time past, filled me with painful sensations; and cannot fail I think, of producing unhappy consequences at home and abroad. With sincere esteem and friendship I am &c. ,-. "•;-- *?• s* Ul 3s, iMj-||M!Kimtn- itlf-i t ? I If M Ill-H i *t * N fUl rji 11M f itHfin-t*> » • M«11H tin i liif||ir»fi j41if s» fi'tit - iPtPf Hl'HWiiMi h STANFORD HISTORY EDUCATION GROUP READING LIKE A Alexander Hamilton Letter to George Washington, 1792 (Modified) Dear Sir, I have received your letter of August 26th. I sincerely regret that you have been made to feel uneasy in your administration. I will do anything to smooth the path of your administration, and heal the differences, though I consider myself the deeply injured party. I /cflowthat I have been an object of total opposition from Mr. Jefferson. I know from the most authentic sources, that I have been the frequent subject of most unkind whispers by him. I have watched a party form in the Legislature, with the single purpose of opposing me. I believe, from all the evidence I possess, that the National Gazette (a newspaper) was instituted by Jefferson for political purposes, with its main purpose to oppose me and my department. Nevertheless, I can truly say that, besides explanations to confidential friends, I never directly or indirectly responded to these attacks, until very recently. But when I saw that they were determined to oppose the banking system, which would ruin the credit and honor of the Nation, I considered it my duty to resist their outrageous behavior. Nevertheless, I pledge my honor to you Sir, that if you shall form a plan to reunite the members of your administration, I will faithfully cooperate. And I will not directly or indirectly say or do a thing to cause a fight. I have the honor to remain Sir, Your most Obedient and Humble servant A Hamilton Source: This letter was written by Alexander Hamilton to President George Washington on September 9, 1792. Hamilton was Secretary of the Treasury in Washington's administration. Hamilton vs. Jefferson STANFORD HISTORY EDUCATION GROUP READING LIKE A Thomas Jefferson Letter to George Washington, 1792 (Modified) DEAR SIR, I received your letter of August 23rd. You note that there have been internal tensions in your administration. These tensions are of great concern to me. I wish that you should know the whole truth. I have never tried to convince members of the legislature to defeat the plans of the Secretary of Treasury. I value too highly their freedom of judgment. I admit that I have, in private conversations, disapproved of the system of the Secretary of Treasury. However, this is because his system stands against liberty, and is designed to undermine and demolish the republic. I would like for these tensions to fade away, and my respect for you is enough motivation to wait to express my thoughts until I am again a private citizen. At that point, however, I reserve the right to write about the issues that concern the republic. I will not let my retirement be ruined by the lies of a man who history—if history stoops to notice him—will remember a person who worked to destroy liberty. -Still, I repeat that I hope I will not have to write such a thing. I trust that you know that I am not an enemy to the republic, nor a waster of the country's money, nor a traitor, as Hamilton has written about me. In the meantime I am with great and sincere affection and respect, dear Sir, your most obedient and most humble servant. Thomas Jefferson Source: This letter was written by Thomas Jefferson to President George Washington on September 9, 1792. Jefferson was Secretary of State in Washington's administration. ~ Hamilton vs. Jefferson Conflict in the Cabinet, 1792: Examining Primary Source Documents Correspondence: George Washington (GW) & Alexander Hamilton (AH) Correspondence: George Washington (GW) & Thomas Jefferson (TJ) 1) What is the purpose of each letter, i.e. why is one man writiriR to the other? 1) What is the purpose of each letter, i.e. why is one man writing to the other? GW to AH (August 26, 1792) GW to TJ (August 23, 1792) AH to GW (September 9, 1792) TJ to GW (September 9, 1792) 2) Describe something from each letter that stood out or caught your attention. 2) Describe something from each letter that stood out or caught your attention. GW to AH (August 26, 1792) GW to TJ (August 23, 1792) AH to GW (September 9, 1792) TJ to GW (September 9, 1792) 3) Choose a quote (1-2 sentences max.) from one of the letters and explain how and why it captures the essence of the conflict in the cabinet. 3) Choose a quote (1-2 sentences max.) from one of the letters and explain how and why it captures the essence of the conflict in the cabinet. In one sentence, and in your own words, describe how the conflict between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson embodies one of our four enduring themes of U.S. History (Nationalism vs. Sectionalism; Federal power vs. States' Rights; Pursuit of Liberty and Equality; People Respond to Incentives). Or, you may create a "bumper sticker" slogan that does the same thing. If you choose the latter, be creative and concise! Please write your answer on the back of this graphic organizer worksheet.