medea adapted: the subaltern barbarian speaks

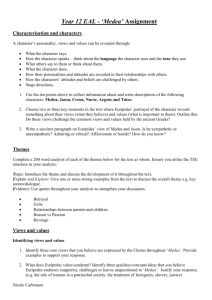

advertisement