Community Perceptions of Theft Seriousness: A Challenge to Model

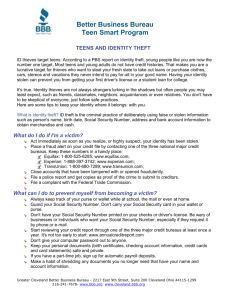

advertisement