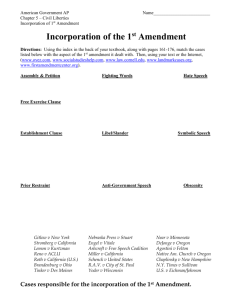

The Incorporation Doctrine: A Legal and Historical Fallacy

advertisement