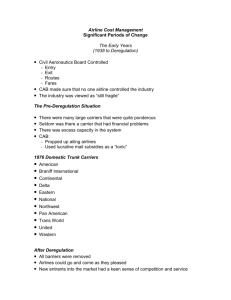

Unscrambling the Eggs: Eastern Air Lines, Delta Air Lines, and the

advertisement