franchise agreements and the application of article 101 tfeu

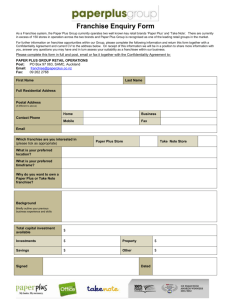

advertisement