Provost Task Force on Learning Communities (report)

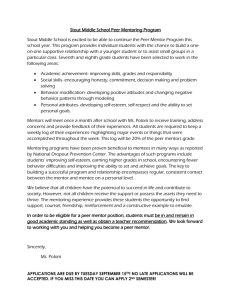

advertisement