Discuss how nurses can contribute to the promotion of health and

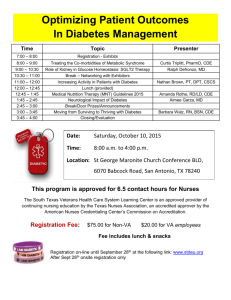

advertisement

Assignment title: Discuss how nurses can contribute to the promotion of health and well-being for individuals who have Type II Diabetes. Abstract: The World Health Organisation has identified diabetes mellitus, of which 90% are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D), as one of the leading causes of death, disability and economic loss throughout the world. In the United Kingdom (UK), diabetes is one of the biggest healthcare challenges facing the National Health Service (NHS) and the number of people developing T2D continues to increase. Health promotion has been recognised as a key strategy for prevention of a T2D epidemic requiring multi-agency cooperation. Being in a unique position in a healthcare professional team, nurses can make a major impact in health promotion. This assignment attempts to explore how nurses when working with other professionals in the multidisciplinary team can promote health and wellbeing for individuals with T2D and their families. Page 1 of 17 The World Health Organisation (WHO 2012a) has identified diabetes mellitus, of which 90% are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D), as one of the leading causes of death, disability and economic loss throughout the world. T2D results from the body’s ineffective utilisation of insulin (WHO 2012a). In the United Kingdom (UK), diabetes is one of the biggest healthcare challenges facing the National Health Service (NHS) and the number of people developing T2D continues to increase (Department of Health (DH) 2010). In 2001, The National Service Framework for Diabetes was published to set out clear minimum standards in relation to prevention, empowerment and education of patients and healthcare professionals in management of diabetes (DH 2001) and continued to monitor strategies to reduce the risk of developing T2D in the population (DH 2010). However, a recent report from Public Account Committee (2012) revealed that the NHS has not been delivering the expected standards of care for a number of years and will be facing ever-increasing cost unless the care improves significantly. Health promotion has been recognised as a key strategy for prevention of a T2D epidemic requiring multi-agency cooperation (Naidoo and Wills 2010). Being in a unique position in a healthcare professional team, nurses can make a major impact in health promotion (Wills 2007). This assignment attempts to explore how nurses and other professionals in the multidisciplinary team can promote health and wellbeing for individuals with T2D and their families. Recently published literature retrieved from databases such as CINAHL, MEDLINE, TRIP, Cochrane Database and ProQuest using search terms such as T2D, epidemiology, health promotion, health education and nursing roles to support the findings. In a culture of increased expectations, accountability and evidence-based practice, nurses have a duty to provide the best care based on the best available evidence for patients with T2D (Nursing and Midwifery Council 2010). These roles would be difficult to fulfil without knowledge and the ability to interpret statistics and epidemiology of Diabetes (Giuliano and Polanowicz 2008). T2D is increasing in every country (Lam and Leroith 2012, WHO 2012a). The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (2011, 2012) estimated diabetes affected 366 million people internationally in 2011, 371 million in 2012 and is expected to reach 552 million by 2030. T2D affects 2.2 million people in the UK and over 60,000 in Northern Ireland (Diabetes UK 2012). Northern Ireland has a lower prevalence compared to the UK Page 2 of 17 average (3.7 percent compares to 4.26 percent) (Diabetes UK 2010a), yet has the highest incidence of patients who were diagnosed with T2D in the last five years, 33% compared to 25% in England, 20% in Wales and 18% in Scotland (Diabetes UK 2012) and costs the health service over one million pounds per day (Diabetes UK 2010b). T2D is caused by a combination of genetic and lifestyle factors. Although unmodified risk factors such as genetic factors, age, race and previous gestational diabetes are considered to be essential, the modifiable factors such as obesity, smoking, physical inactivity, nutrition and lifestyle are major reasons for increase in prevalence (Alberti et al. 2007). WHO (2012b) suggests that if modifiable risk factors were eliminated, up to 80% of T2D would be prevented. T2D usually occurs in adults after the over 40, but increasingly is seen in children and adolescents with the increased prevalence of obesity (Haines et al. 2007, IDF 2012). There is a higher incidence of T2D among some ethnic groups such as black, African and Asian origin (Strayer and Schub 2012). Using the knowledge of epidemiology and determinants for T2D, nurses can identify individual needs by themselves or through patient’s expression and target their services at vulnerable groups and communities (Ghosh et al. 2010, Janssens et al. 2011). Research has shown individuals from lower socioeconomically, deprived areas are at greater risk of T2D (Harper and Lynch 2007). Due to occupation, education level, economic status and lack of awareness of available health service, these individual are less likely to attend for blood tests and hence often remain undiagnosed (Endevelt et al. 2009). The understanding of determinant factors helps nurses target high risk groups and draw up preventative strategies to tackle these problems (Balasanthiran et al. 2012). However, nurses still lack ability to do so despite the clear benefits (Brown et al. 2009). The Department of Health has published documentation that clearly outlines the strategy for reducing prevalence of T2D and associated complications (DH 2001, DH 2003, DH 2004, DH 2008a, DH 2008b). The targets for intervention are focused on the role of prevention in improving the nation’s health. Primary prevention and community care settings are recognised as vital parts of health and social care strategy. Individuals will be working in partnership with healthcare Page 3 of 17 professionals and agencies and taking more responsibility for their own health (DH 2006). The prevention strategies are adopted in all stages of disease (Kiger 2004) and patient education is widely accepted as a fundamental part of treatment of T2D (Molsted et al. 2012). The Munich Declaration recognised the unique roles and contribution of nursing as a “force for health” in tackling the public health challenge (WHO 2000) and can contribute significantly in prevention of T2D epidemic (Forbes 2011). Health promoting lifestyle is most useful as the primary approach in preventing diabetes (Nathan et al. 2007). Pre-emptive actions in primary prevention to tackle risk factors such as healthy diet, daily exercises, smoking cessation and losing weight are most effective in preventing or delaying the onset of T2D (Ramachandran et al. 2006, Willems et al. 2011). Obesity is a major risk factor and co-morbidity of T2D that predisposes patients to significant end-organ damage (NICE 2011, Shaseddeen et al. 2011). Nurses could help parents and children by providing nutritional advice or strategies for decreasing caloric intake and increasing physical activities (Rabbitt and Coyne 2012). Addressing issues and suggesting changes can be challenging for nurses when the information seems repetitive and uninspiring and the individuals often have their own explanation on their lifestyle or diet to resist the change (Randle 2010). Nurses need to be prepared for this type of reaction and find better ways to get the message across to their patients without them feeling bossed or controlled (Deakin 2006). However, nurses need to assess the individual’s needs and balance how much information to give to avoid information overload (Oftedal et al. 2010). Also the use of teaching methods and materials should be appropriate, especially for those from ethnic groups, those with poor literacy skills or deficits in cognitive status (Xu et al. 2010, Punthakee et al. 2012). The UK Government acknowledges that nurses are a trusted source of information for people seeking advice about their lifestyle and encourages nurses to be more proactive in helping the public (Robinson 2008). Secondary prevention is aimed at making an early diagnosis in order to prevent the progression of disease (Dankner et al. 2009, NICE 2011). Evidence suggests that years of undiagnosed diabetes and hyperglycaemia will lead to severe Page 4 of 17 complication such as blindness, stroke, cardiovascular disease and limb amputations (NICE 2011). Structured education should be offered to individuals and their carers at and around the time of diagnosis and reinforced at annual review (DH and Diabetes UK 2005, NICE 2008). Nurses can address the importance of health checks and encourage individuals to attend annual screening checks, such as neuropathy, retinopathy, cardiovascular and renal function (NICE 2012). Nurses should always raise awareness of health protection to individuals with T2D such as supporting policy on smoking or driving (Hesman 2007). Although driving is more applicable for type 1, nurses cannot overlook the wide range of complications arising from T2D. Up to 90% of patients with T2D have obstructive sleep apnoea (Heffner et al 2012) and this could affect their possibility to attain a driving licence (Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency 2011). Tertiary prevention is aimed at the actions required to avoid unnecessary disease progression or complications such as disability or recurrence of illness. Nurses have an important role in controlling and monitoring the progression of T2D (Wellard et al. 2007). Nurses can teach patients about foot care, eye care, administration of medication such as insulin or self-monitoring blood glucose levels (Gulanick and Myers 2007). Further reinforcement of diet and healthy lifestyle is addressed at this stage to help patients maintain their current state and prevent further deterioration. Nurses, multidisciplinary team members and patients need to work together to identify any signs or symptoms of complications in order to act promptly. (Nikolaos and Efstratios 2010). Patient education is not only essential to promote health and prevent complications but is also necessary to empower individuals with chronic illnesses associated with T2D (Visser and Snoek 2004). Nurses are often good at individualistic approaches but less familiar with broader public health promotion such as group education (Watson 2008). Although there is no clear evidence to prove group is more effective than individual education, nurses need to adopt the most appropriate approach to achieve the best outcomes. (Duke et al. 2009). Self-management programmes such as DESMOND – Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed - are set up to empower, educate and give patients a sense of control (Lorig et al. 2009) and improve outcomes in HbA1c and Body Page 5 of 17 Mass Index (Mollaoglu and Beyazit 2009). Nurses need to be aware of these programmes and facilitate individuals to develop a self care plan or improve their skills in self care (Hall 2009, Richards 2012). Nurses should also be aware of cultural obstacles and limitations that prevent many ethnic nationals from engaging in these programmes (Hsu et al. 2006). The shifting of health care provision from the hospital to the community setting has emphasised the focus on prevention (Watson 2008). In reality, healthcare professionals are often consumed with downstream interventions, tertiary prevention such as treatment of T2D or its complications (Carter 2003). However, nurses should take opportunities to working upstream when possible (McBean 2006) to seek the causes of disease and preventable disability in order to address problems through prevention, rather than treatment (RCN 2012). Recent government strategies have paved the way for a stronger, more effective contribution to health promotion for nurses (DHSSPS 2003, DHSSPS 2005). Nurses are encouraged to work with local multidisciplinary and inter-agency teams to help improve living conditions of people with T2D such as housing or transportation and address health inequalities (Ewles and Simmett 2003, Naidoo and Wills 2010). Nurses cannot deliver efficient and effective care to patients with T2D and their family without the assistance of the multidisciplinary team (Chen et al. 2011). Research shows that not all nurses are confident in diabetes care and have to rely on diabetes specialist nurses (DSNs) (Wellard et al. 2007). Practitioner nurses (PNs) and DSNs have more privileged roles within the multidisciplinary team and often act as co-ordinators of patient care (James et al. 2009). PNs have a unique role in screening patients for T2D and have key responsibilities in communicating any concerns regarding their patients with the team. DSNs are now solely responsible for the specialised management of care of diabetes (Edwall et al 2010). The emerging role of the Diabetes Research Nurse will also contribute to enhance the promotion of health in the future (Forbes 2011). Working within the multidisciplinary team, nurses should know where and when to make appropriate referrals and liaise with other professionals such as GP’s, dieticians, podiatrists, ophthalmologists and dermatologists in order to provide tailored, holistic framework of care for patients (van Bruggen et al. 2008, Robinson 2011). For example, if a Page 6 of 17 patient is having difficulty with mobility the nurse may refer them to a physiotherapist (Taylor et al. 2009). Nurses could also use both expert power and personal power to encourage local health and social care authorities to set up a ‘diabetes housebound team’ to offer housebound patients regular reviews (Wood 2009) or request grants for amputees as a result of T2D. However, the multidisciplinary team approach, can be time consuming, difficult to organise, requires highly developed communication and collaborative skills, and good leadership (Vagholkar et al. 2007, Wood 2009). Cooperation with family is likely to help nurses in producing the most accurate nursing diagnosis and most effective interventions (Kumar 2007). Nurses could enlarge the scope of health promotion as they fulfil the patient’s and family’s educational needs about T2D and the risk factors associated with it, hence improve the awareness of the disease in the wider circle (Orvik et al. 2010). It is important that nurses remember to provide psychological care for patients with T2D as research has shown they are susceptible to depression (Mezuk et al. 2008, Ruddock et al. 2010). Spiritual needs also need to be addressed as it significantly affects some patients’ ability to cope with illness or self management (Polzer and Miles 2005). Research shows that working with the church has helped nurses implement health education programmes successfully for some patients with T2D with positive psychological outcomes (Samuel-Hodge et al. 2008). As healthcare professionals, nurses spend a great deal of time with patients in hospital and in the community and can significantly contribute to health promotion. The nurses’ role in prevention of T2D, educating individuals to cope with the illness, providing care in the community or promotion of health policies is undeniable. The rising demand for diabetes care requires nurses to work efficiently in collaboration with multidisciplinary teams to control the diabetes epidemic and provide the highest quality of care and support for patients and their families. All nurses, whether specialised or generally trained, can contribute to promoting health and wellbeing to individuals with T2D and to the public. REFERENCES: Page 7 of 17 Alberti, K.G., Zimmet, P. and Shaw, J. 2007. International Diabetes Federation: a consensus on Type 2 diabetes prevention. Diabetes Medicine, 24, 451-463. Balasanthiran, A., O’Shea, T., Moodambail, A., Woodcock, T., Poots, A. J., Stacy, M. And Vijayaraghavan, S. 2012. Type 2 diabetes in children and young adults in East London: an alarming high prevalence. Practical Diabetes, 29(5), 193-8. Brown, C., Wickline, M., Ecoff, L. and Glaser, D. 2009. Nursing practice, knowledge, attitudes and perceived barriers to evidence-based practice at an academic medical centre. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(2), 371-381. Carter, T. 2003. Working upstream for those working downstream. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand, 9(5), 31. Chen, M. Y., Huang, W. C., Peng, Y. S., Guo, J. S., Chen, C. P., Jong, M. C. and Lin, H. C. 2011. Effectiveness of a health promotion programme for farmers and fishermen with type-2 diabetes in Taiwan. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(9), 2060-7. Dankner, R., Geulayov, G., Olmer, L. and Kaplan, G. 2009. Undetected type 2 diabetes in older adults. Age and Ageing, 38(1), 56-62. Deakin, T. A., Cade, J. E., Williams, R. and Greenwood, D. 2006. Structured patient education: The diabetes x-pert programme makes a difference. Diabetes Medicine, 23(9), 944-954. Department of Health. 2001. National Service Framework for Diabetes: Standard. London: Department of Health. Department of Health. 2003. National Service Framework for Diabetes: Delivery Strategy. London: Department of Health. Page 8 of 17 Department of Health. 2004. Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. (Cm 6374). London: The Stationery Office. Department of Health. 2006. Our health, our care, our say: A new direction for community services. (Cm 6737). London: The Stationery Office. Department of Health. 2008a. Healthy weight, healthy lives: a cross-government strategy for England. London: Department of Health. Department of Health. 2008b. Putting prevention first- vascular checks: risk assessment and management. London: Department of Health. Department of Health. 2010. Six Years On Delivering the Diabetes National Service Framework. London: Department of Health. Department of Health and Diabetes UK. 2005. Structured Patient Education in Diabetes. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/docume nts/digitalasset/dh_4113217.pdf [Accessed 22 November 2012]. Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. 2003. From vision to action: strengthen the nursing contribution to public health. Belfast: DHSSPS. Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. 2005. Nursing for public health: realising the vision- a model for putting public health into practice. Belfast: DHSSPS. Diabetes UK. 2010a. Diabetes Prevalance 2010. Available at: http://www.diabetes.org.uk/About_us/Press-centre/Key-diabetes-statistics-andreports/Diabetes-prevalence-2010/ [Assessed 20 November 2012]. Page 9 of 17 Diabetes UK. 2010b. Health in Northern Ireland better but obesity and diabetes rising. Available at: http://www.diabetes.co.uk/news/2010/Feb/health-in-northernireland-better-but-obesity-and-diabetes-rising-91346434.html [Assessed 20 November 2012]. Diabetes UK. 2012. 1 in 4 children left seriously ill as vital diabetes symptoms are missed. Available at: http://www.diabetes.org.uk/In_Your_Area/N_Ireland/News/ [Assessed 20 November 2012]. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. 2011. Changes to the standards for drivers with diabetes mellitus – latest update. Available at: http://www.dft.gov.uk/dvla/medical/Annex%203%20changes%20to%20the%20stan dards%20for%20drivers%20with%20diabetes%20mellitus%20Latest%20Update.a spx [Assessed 20 November 2012] Duke, S. A. S., Colagiuri, S. and Colagiuri, R. 2009. Individual patient education for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD005268. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005268.pub2 Edwall, L., Ella, D. and Ohrn, I. 2010. The meaning of a consultation with the diabetes nurse specialist. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 24(2), 341-348. Endevelt, R., Baron-Epel, O., Karpati, T. and Heymann, A. 2009. Does low socioeconomic status affect use of nutritional services by pre-diabetes patients? International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 22(2), 157-167. Ewles, L and Simnett, I. 2003. Promoting Health: A Practical Guide to Health Education. 5th ed. London: Baillière Tindall. Forbes, A. 2011. Progressing diabetes nursing in Europe: the next steps. European Diabetes Nursing, 8(1), 8-10. Ghosh, A., Liu, T., Khoury, M. and Valdez, 2010. Family history of diabetes and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in U. S. adults without diabetes: 6-year results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Genomics (1999-2004), 13(6), 353-359. Page 10 of 17 Giuliano, K.K. and Polanowicz, M. 2008. Interpretation and use of statistics in nursing research. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 19(2), 211-22. Gulanick, M. and Myers, J. L. 2007. Nursing care plans: Nursing diagnosis and intervention. 6th ed. Missouri: Mosby Elsevier. Haines, L.L., Wan, K.C., Lynn, R.R., Barrett, T. G. And Shield, J.P.H. 2007. Rising incidence of type 2 diabetes in children in the U.K. Diabetes care, 30(5), 10971101. Hall, G. 2009. Developing and using careplans in type 2 diabetes. Practice Nurse, 37 (10), 36-9. Harper, S. and Lynch, J. 2007. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in adult health behaviours among U.S. States. 1990-2004. Public Health Reports, 122(27), 177189. Heffner, J. E., Rozenfeld, Y., Kai, M. Stephen, E.A. and Brown, L.K. 2012. Prevelance of diagnosed sleep apnea among patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care. Chest, 141(6), 1414-21. Hesman, A. 2007. Protecting the Health of the Population. In: Wills, J. ed. Vital notes for nurses: promoting health. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 110-128. Hsu, W. C., Cheung, S. and Ong, O. 2006. Identification of linguistic barriers to diabetes knowledge and glycamic control in Chinese Americans with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 29(4), 415-416. International Diabetes Federation. 2011. The IDF Diabetes Atlas, 5th ed. Brussels: IDF Page 11 of 17 International Diabetes Federation. 2012. The IDF Diabetes Atlas, 5th ed. Update 2012. Brussels: IDF. James, J., Gosden, C., Winocourt, P., Walton, C., Nagis, D., Turner, B., Williams, R. and Holt, R. I. G. 2009. Special Report: Diabetes specialist nurses and role envolvement: a survey by Diabetes UK and ABCD of specialist diabetes services 2007. Diabetes Medicine, 26, 560-565. Janssens, A. C., Ioannidis, J. P., vanDuijin, C., Little, J. and Khoury, M. J. 2011. Strengthening the reporting of genetic risk prediction studies: The GRIPS statement. European Journal of Epidemiology, 26(4), 255-259. Kiger, A. M. 2004. Teaching for health. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchhill Livingstone. Elsevier Ltd. Kumar, C. P. 2007. Application of Orem’s self-care deficit theory and standardize nursing languages in a case study of a woman with diabetes. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 18(3), 103-10. Lam, D. W. and Leroith, D. 2012. The worldwide diabetes epidemic. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, 19 (2), 93-6. Lorig, K., Ritter, P. L., Villa F. J. and Armas, J. 2009. Community-based peer-led diabetes self-management: a randomized trial. Diabetes Educator, 35(4), 641-51. McBean, S. 2006. Evolution and diversification of nurses and nursing in relation to public health: Correlating policy and current job opportunities in Scotland, Northern Ireland and England. In: Tavakoli, M and Davies, H. T. O. eds. Reforming Health Systems: Analysis and Evidence. St Andrews: Tavakoli, M. and Davies, H. T. O. 203-219. Mezuk, B., Eaton, W. W., Albrecht, S. and Golden, S. H. 2008. Depression and Type 2 diabetes over the lifespan. A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care, 31(12), 23832390. Page 12 of 17 Mollaoglu, M. and Beyazit, E. 2009. Influence of diabetic education on patient metabolic control. Applied Nursing Research. 22(3), 183-190. Molsted, S., Tribler, J., Poulsen, P. B. and Snorgaard, O. 2012. The effects and costs of a group-based education programme for self-management of patient with type 2 diabetes. A community based study. Health Education Research, 27(5), 804-13. Naidoo, J. and Wills, J. 2010. Developing Practice for Public Health and Health Promotion. Edinburgh: Bailliere Tindall Elsevier Ltd. Nathan, D. M., Davidson, M. B., Defronzo, R. A., Heine, R. J., Henry, R. R., Pratley, R. and Zinman, B. 2007. Impair fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: implications for care. Diabetes Care, 30, 753-759. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2008. Type 2 Diabetes: Management of Type 2 diabetes. Guideline CG66. London: NICE. National Institution for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2011. Preventing type 2 diabetes: population and community-level interventions in high-risk groups and the general population. Guidance PH 35. London: NICE. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2012. Preventing type 2 diabetes: risk identification and interventions for individual at high risk. Guidance PH 38. London: NICE. Nikolaos, P. and Efstratios, M. 2010. The diabetes hand: a forgotten complication? Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 24, 154-162. Page 13 of 17 Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2010. The Code: Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics for Nurses and Midwives. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council. Oftedal, B., Karlsen, B. and Bru, E. 2010. Life values and self-regulations behaviour among adults with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(17), 2548-2556. Orvik, E., Ribu, L. and Johansen, O. E. 2010. Spouses’ educational needs and perceptions of health in partners with type 2 diabetes. European Diabetes Nursing, 7(2), 63-9. Piper, S. 2009. Health Promotion for Nurses: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. Polzer, R and Miles, M. S. 2005. Spirituality and self-management of diabetes in African Americans. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23(2), 224-9. Public Accounts Committee. 2012. Seventeenth Report: Department of Health: The management of adult diabetes services in the NHS. London: Public Accounts Committee. Puthakee, Z., Miller, M. E., Launer, L. J., Williamson, J. D., Lazar, R. M., Cukierman-Yaffee, T., Seaquist E. R., Ismail-Beigi, F., Sullivan, M. D., Lovato, L. C., Bergenstal, R. M. and Gerstein, H. C. 2012. Poor cognitive function and risk of severe hypoglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: post hoc epidemiologic analysis of the ACCORD trial. Diabetes Care, 35(4), 787-93. Rabbitt, A. and Coyne, I. 2012. Childhood obesity: nurses’ role in addressing the epidemic. Bristish Journal of Nursing, 21(12), 731-5. Ramachandran, A., Snehalatha, C., Mary, S., Mukesh, B., Bhaskar, A.D. and Vijay, V. 2006. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Progmamme shows that lifestyle Page 14 of 17 modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1). Diabetologia, 49(2), 289-297. Randle, A. 2010. Lifestyle event for diabetes patients. Practice Nurse, 40(5), 35-9. Richards, S. 2012. Self care – a nursing essential. Practice Nurse, 42(11), 26-30. Robinson, F. 2008. New obesity strategy. Practice Nurse, 35(3), 10-11. Robinson, F. 2011. The role of the district nurse. Practice Nurse, 41(8), 30-1. Royal College of Nursing. 2012. Going upstream: Nursing’s contribution to public health - Prevent, promote and protect - RCN guidance for nurses. London: RCN. Ruddock, S., Fosbury, J., Smith, A., Meadows, K. and Crown, A. 2010. Measuring psychological morbidity for diabetes commissioning: a cross-sectional survey of patients attending a secondary care diabetes clinic. Practical Diabetes International, 27(1), 22-6. Samuel-Hodge, C. D., Watkins, D. C., Rowell, K. L. and Hooten, E. G. 2008. Coping styles, well-being and self-care behaviours among African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educator, 34(3), 501-10. Shamseddeen, H., Getty, J. Z., Hamdallah, I. N. and Ali, M. R. 2011. Epidemiology and economic impact of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Surgical Clinics of North America, 91(6), 1163-72. Strayer, D. A. and Schub, T. 2012. Quick lesson about Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2. Cinahl Information Systems. California: Cinahl Information Systems. Page 15 of 17 Taylor, D. J., Fletcher, J. P. and Tiarks, J. 2009. Impact of physical therapistdirected exercise counselling combined with fitness center-based exercise training on muscular strength and exercise capacity in people with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical Trial. Physical Therapy, 89(9), 884-892. Vagholkar, S., Hermiz, O., Zwar, N. A., Shortus, T., Comino, E.J. and Harris, M. 2007. Multidisciplinary care plans for diabetic patients - what do they contain? Australian Family Physician, 36 (4), 279-82. Van Bruggen, R., Gorter, K. J., Stolk, R. P. Verhoeven, R. P. and Rutten G. E. 2008. Family Practice, 25(6), 430-7. Visser, A. and Snoek, F. 2004. Perspectives on education and counselling for diabetes patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 53, 251–255. Watson, M. 2008. Going for gold: the health promoting general practice. Quality in Primary Care, 16(3), 177-185. Wellard, S. J., Cox, H. and Bhujoharry, C. 2007. Issues in the provision of nursing care to people undergoing cariodiac surgery who also have type 2 diabetes. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 13(4), 222-8. Willems, S., Mihaescu, R., Sijbrands, E., Cornelia, M., Van Duijn, A., Cecile, W. and Janssens, A. 2011. Methodological Perspective on Genetic Risk Prediction Studies in Type 2 Diabetes: Recommendations for Future Research. Current Diabetes Reports, 11(6), 511-518. Wills, J. 2007. The Role of the Nurse in Promoting Health. In: Wills, J. ed. Vital Notes for Nurses: Promoting Health. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 1-10. Wood, J. 2009. Supporting vulnerable adults. Practice Nursing, 20(10), 511-5. Page 16 of 17 World Health Organisation. 2000. Munich Declaration: Nurses and midwives: a Force for Health. Geneva: WHO. World Health Organisation. 2012a. Diabetes. Fact sheet Number 312. Geneva: WHO. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/index.html [Assessed 20 November 2012]. World Health Organisation. 2012b. Protocols for health promotion, prevention and management of non-communicable diseases at primary care level. Geneva: WHO. Available at: http://www.afro.who.int/en/clusters-a-programmes/dpc/noncommunicable-diseases-managementndm/npc-features/2257-who-penprotocols.html [Assessed 20 November 2012]. Xu, Y., Pan, W. and Liu, H. 2010. Self-management practices of Chinese Americans with type 2 diabetes. Nursing and Health Sciences, 12(2), 228-234. Page 17 of 17