Early Marriage - UNICEF

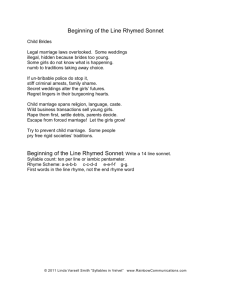

advertisement