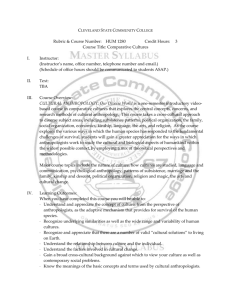

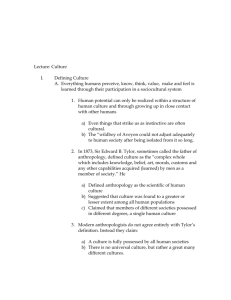

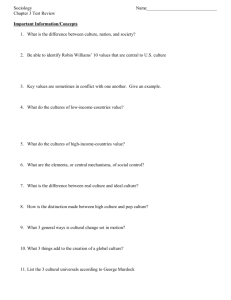

Culture: Definition, Components, and Human Life

advertisement