transnational freezing orders

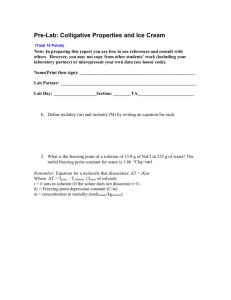

advertisement