CHAPTER 8:

advertisement

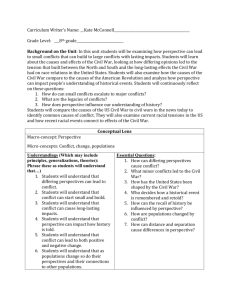

CHAPTER 8: CONFLICT MANAGEMENT Chapter Outline 1. Conflict Defined Definition Communication-based conflict 2. Consequences of Conflict Constructive consequences Destructive consequences Competition vs. cooperation 3. Conflict Locations Complexities in identifying conflict Communication units Management units 4. Conflict Location Matrix 5. Conflict Management Strategies Power Compromise Creative Alternative 6. Management Tactics Third-party intervention Principles 7. Personal Conflict Management Styles Neglector Accommodator Driver Compromiser Expressive During the 1960's and 1970's, social unrest and international conflict (especially in Viet Nam) motivated social scientists to investigate the destructive effects of conflict. A primary end-goal was to promote societal and international harmony. Consequently, much of the literature from that period of time viewed conflict as negative and distasteful. Many scholars and managers sought to avoid controversy and disagreement. Today, a more balanced view of conflict exists. Now, we acknowledge that conflict has functional and dysfunctional components. So, the purpose of this chapter is to highlight both sides from the perspective that conflict is inevitable and must be continually managed in order to maximize positive outcomes and minimize negative consequences. Conflict Defined Definitions of conflict have been developed from several perspectives. Psychologists focus on internal conflict that predisposes an individual to behavior in specific ways. Social psychologists have looked at different environmental settings that 8-1 provoke disparate, competing tendencies in individual behavior. Sociologists view conflict as the result of competing interests between groups of people. Definition. Although different perspectives of conflict exist, there is one commonality: each point of view describes conflict as occurring when there are two or more competing, often incompatible responses to a single event. Conflict occurs when there are two or more competing responses to a single event. Competing responses may exist without conflict. If participants do not perceive discrepancies among options, conflict will not occur. But, competing responses need not exist for conflict to occur; the mere perception of competing responses among parties is sufficient for conflict to occur. Communication-based conflict. Communication conflicts are an outgrowth of the use of symbols. As indicated in Chapter 2, communication behaviors are a multidimensional act with process (source vs. receiver), content (work vs. person), and functional (information exchange, problem/solution identification, behavior regulation, conflict management) characteristics. These can induce conditions for conflict. Process conflict. When there is disagreement about who should be enacting source and receiver roles, a communication process role conflict exists. That is why organizations often designate an individual as a spokesperson for certain events, e.g., crisis management, product announcements, etc. Content conflict. When there is disagreement about work- or person-related messages and issues, a communication Communication conflict occurs when: content role conflict exists. That is why 1. organizations have found it necessary to 2. create separate functions for each. In 3. 4. 5. 6. Chapter 2 we described Katz and Kahn’s theoretical distinction between There is disagreement about source and receiver role enactment. There is disagreement about work- or personrelated messages and issues. Different information exists. Different problems & solutions are identified. Different regulation strategies are preferred. Different conflict strategies are preferred. mainte nance and production or technical subsystems. This distinction is analogous to of human resources or personnel 8-2 processes being housed separately from production processes. The content is different and separate functions are needed to manage each and to maintain a constructive balance between the two. Information conflict. Information concerning the same issue can vary widely; what one knows to be true, another may believe is false. This can lead to conflict. There is a peculiar paradox in information flow. Subordinates view high-status individuals as having access to and control over information. On the other hand, managers often express uncertainty about massive amounts of information they must sort, chunk, or organize to determine what is really going on. So, what may be viewed as certainty from one perspective, may actually be a high level of confusion from another. This paradox is often combined with another consequence of information flow – subordinates do not like to give supervisors negative information. So, a supervisor will likely hear the positives and not discover the negatives. This situation produces a distortion of reality. Problem/solution identification conflict. Organizations remove barriers and achieve goals by using problem solving processes. As problem complexities increase, greater amounts of information are required. The search for greater amounts of information increases the likelihood of competing perceptions about the problem and potential solutions. These, in turn, promote conflict over the problems and solutions identified. Behavior regulation conflict. Organizations may attempt to manage behavior through friendship (identification), appeals to values and logic (internalization), or by specifying consequences of actions (compliance). Communication patterns and content easily reveal the strategies being used. Consider the following example: An executive calls in a high-level supervisor and asks how the supervisor ensures that workers will get the job done. Not happy with the reply, the executive – perhaps possessing a preference for maintaining relationships – tells the supervisor that he doesn’t care for the supervisor’s tactics. The supervisor 8-3 replies, “When I came here, if people didn’t pull their weight, we fined or fired them!!” Obviously, a conflict exists between the executive and the supervisor. This type of conflict is common and has cultural, value -laden bases. Conflict strategy conflict. When conflicts become prominent, conflict management strategies are inevitably discussed. When there is divergence in preferred strategies, a meta-conflict (i.e., conflict over conflict strategy selection) exists. These can be serious if ineffectively dealt with. At the very least, they contribute to a delay in managing the issue that gave rise to the meta-conflict. Organizational culture contains beliefs about the best way to manage conflict. As a result, organizations have an affinity for strategies that have been previously successful. Excessive reliance on one strategy, especially when other approaches are totally excluded from consideration, creates a greater likelihood for meta -conflict. And, logically, this condition may limit consideration of viable alternatives. Consequences of Conflict Conflict is not inherently good or evil. It is usually effectively or ineffectively managed. The shift in perspective described above implies that efforts to eliminate conflict may actually yield a loss in potentially positive outcomes. Modern researchers have downplayed the likelihood of conflict elimination, opting instead for conflict management. Thus, the study of conflict is no longer viewed as the study of conflict resolution, but rather the study of conflict control. Constructive consequences of conflict . Research suggests that effective conflict management can be beneficial. Indeed, Constructive Consequences suppression or elimination may have negative repercussions. Positive, constructive outcomes include motivation, improved problem solving, goal attainment, cohesion, reality adjustment, and benefits for others. 8-4 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Increased motivation Enhanced motivation Enhanced likelihood of goal attainment Stimulation of cohesion Reality adjustment Benefits for others 1. Increased motivation. A complete absence of conflict is related to inactivity and lack of involvement – perhaps, boredom. Theories of motivation shifted in the middle 20th Century from view that organisms behave to reduce tension to the perspective that organisms seek to maintain optimal levels of stimulation (Allport, 1953; Driver & Streufurt, 1964). In other words, a useful level of stimulation and tension must be maintained or motivation will diminish. 2. Enhanced problem solving. When people have different points of view and confront one another with their positions, there is greater likelihood for producing superior solutions (Thomas, 1976). In other words, diversity leads to consideration of more alternatives. That premise, along with the concept of academic freedom, has allowed universities to be “battlegrounds of ideas,” reaping many advantages from unconstrained discussion without fear of retaliation. 3. Enhanced likelihood of goal attainment. When conflict is avoided or ignored, there is an increased likelihood that the current “state of affairs” will persist. For example, bureaucracy tends to use rules and policies to maintain operations across circumstances; “don’t rock the boat” literally becomes the order of the day. The net result is an impedance of progress and change. We organizational members approach conflict rationally, they are in greater control of the situation and there is increased likelihood for goal attainment (Thomas, 1976). 4. Facilitates reality adjustment. Sometimes individuals develop distorted views of their importance and level of contribution. Consequently, when actions come into conflict, settling a dispute often causes individuals to reassess their value more in line with reality (Thomas, 1976). 5. Benefits for others. As indicated above, conflict can enhance problem solving activity and goal attainment. As conflicts are manage, individuals and organizations have the potential to reap creative, alternative solutions not 8-5 previously considered. One party’s gain may also be a gain for another; improving one’s position may do the same for another (Thomas, 1976). Destructive effects of conflict . Mismanaged conflict can be detrimental. Several negative effects have been identified: coalitions, isolation, lowered satisfaction, lowered productivity, gatekeeping, less participation in problem solving, reliance on compliance behavior regulation, and reliance on power conflict management. 1. Coalition formation. Poorly managed conflict commonly leads to perceptions of threat (Zaltman & Duncan, 1978). When threatened, individuals seek 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Destructive Effects Coalitions Isolation Lowered satisfaction Lowered productivity Gatekeeping Less participation in problem solving Reliance on compliance for behavior regulation Reliance on power for conflict management others with similar points of view; coalitions are formed and battle lines are drawn. Outsiders aren’t communicated with and appear less attractive. Outsiders are viewed with suspicion and appear less credible. Competitors stereotype each other. Information exchange is distorted with the potential for misinformation and deceptive practices. When coalitions form, conflict sources are difficult to determine. 2. Isolation. Obviously, coalition formation will cause individuals to be isolated from those not in the group. Sometimes isolation is self-imposed, a kind of pouting often associated with a feeling of being “ripped off.” Or, it may be imposed on an individual or group when behavior that deviates from group norms. When people are isolated (regardless of their location in the hierarch), they DO NOT ENJOY THEIR WORK. They become suspicious and exhibit higher levels of absenteeism. 3. Lowered Satisfaction. The primary contributors to satisfaction are relations with supervision, subordinates, and co-workers. Since these are the main 8-6 relationships one experiences at work, mismanaged conflict can impair these relations and have an immediate, adverse impact satisfaction levels. 4. Lowered productivity. Many tasks require cooperation and coordination. But, when conflict occurs cooperative efforts are reduced. Consequently, productivity levels become suppressed. 5. Gatekeeping. Parties in conflict gatekeep or restrict information flow. And, information shared is often distorted. Finally, employees will become defensive. For example, managers who rely on power strategies often find that subordinates pass positive information upward and suppress information that could be negative. It then becomes difficult to get an accurate account of operations. 6. Less participation in problem solving. Effective problem solving involves some risk taking and open information exchange. Poorly managed conflict, with consequent coalition formation, isolation, and gatekeeping, stimulates conditions counter to supportive problem-solving environments and creates conditions where employees feel that risk taking is too dangerous. The attitude of “go along to get along,” represents a failure to manage conflict constructively. 7. Reliance on compliance for behavior regulation. Mismanaged conflict may force managers to rely on power, status, and authority to manage behaviors. A great deal of money and energy is invested to ensure that people do as they are told. Supervisory costs will escalate. In these circumstances, open communication or role exchange is restricted -- supervisors are primarily communication sources and subordinates are primarily communication receivers. Most downward information is typically about consequences of non-compliance. The overall amount of formal information given subordinates tends to be reduced. Unofficial information, often received from allies through informal networks, is frequently distorted. 8-7 8. Reliance on power for conflict management. An organization with mismanaged conflict is like a soldier at war. There is tendency to handle the conflict through application of power (what we later describe at a win-lose strategy). Managers assert their positions of power and feel the only alternatives are winning and losing. If forced t compromise, often they are afraid that all will fall apart unless the compromise is achieved quickly. Unfortunately, this leads to limited alternatives and reduces the potential for organizational effectiveness. Competition vs. cooperation. This chapter began with a conflict definition and discussion of consequences. This was provided to facilitate a more balanced view and to provide illustrations of common antecedents and consequences that occur in organizational relationships. A bottom line perspective suggests “conflict is inevitable.” Therefore, relations require continual management. Our experience and review of the literature has caused us to draw this simple observation reflects a philosophy for conflict management: “Effective conflict managers will strive to maximize interpersonal cooperation and optimize intergroup competition.” What does this mean? Simply this – when individuals are placed in competition with one another there is an adverse impact on their relationships that most often results in negative consequences of conflict. For example, retail sales people who are paid by sales volume often restrict information flow and avoid participating in activities that could cause them to lose a customer to another sales person. In this circumstance there is a winner and a loser. In the long run, the organization is also a loser. Consequently, group incentive plans have provided an alternative that capitalizes on constructive effects and reduces negative consequences since it is in everyone’s best interest to be cooperative. Optimizing intergroup competition means finding some method to encourage collective activity for the work group. It may be dangerous to place groups in competition with respect to production quotas. However, there are some very viable, non-threatening competitive activities that have been used by companies. For example, many companies sponsor organized athletic teams. One of the authors helped a retail store develop healthy, competitive activities by starting a corporate bowling league. The company had over 300 employees who didn’t know anyone 8-8 except persons in their department. There had been many cases departments luring customers from each other and a high level of tension. The bowling teams were department-based and the schedule was such that every department bowled against every other department at least twice during the season. Over the four-month period, the non-work based competition fostered a spirit of healthy, constructive competition. Casual acquaintances became friends. Discussions of the sales floor were often about previous and upcoming bowling competition. In addition, there was a lot of healthy chiding and teasing across departmental boundaries. The net result was a decrease in “customer theft,” supportive relationships, and a general experience of good will. Conflict Locations Complexities in identifying conflict. The interaction of people, work processes, culture, and personal needs create elaborate networks of pressure and make conflict identification a somewhat complex activity. Just as problem/solution identification works best when problems and solutions are clearly and comprehensively defined, conflict management requires careful and thorough identification. In a very real sense, problem/solution identification and conflict management processes must operate “hand-in-hand.” Not all conflicts are communication conflicts; all are not management conflicts. For e xample, identification requires value-system definition. Often, communication is a symptom of an underlying value difference. Thus, in a larger sense, identification proceeds with a concern for separating symptoms from causes (much like the issues raised in chapter 7). Individuals “carry” their values with them when they enter an organization. Sometime, these values are acquired from previous experiences, training, family, etc. Scholars and practicing managers indicate the positive changes can occur when new people join an organization and inject new ideas, beliefs, and values. However, change rarely occurs without some type of conflict. Effective management requires locating the conflict or identifying the unit of analysis or system in which the conflict exists. 8-9 Communication units. Communication theory and practice provides one perspective for defining a conflict’s location, unit of analysis, or system. There are six primary communication units: 1. Intrapersonal. Intrapersonal conflict is psychological conflict. The unit of analysis is the individual. Management focuses on dealing with an individual’s internal issues (i.e., subsystems). 2. Interpersonal. Interpersonal conflict may be psychological and social. The unit of analysis includes the individual and the ways that individual initiates and manages relations with others. 3. Intragroup. Intragroup conflict includes intrapersonal and interpersonal subsystems within a specific work group. 4. Intergroup. Intergroup conflict exists when subsystems contain two or more work groups within an organization. Typically intergroup refers to relatively few groups in conflict. 5. Intraorganizational. Intergroup and intraorganizational can be equivalent terms. Generally, however, intraorganizational is the unit of analysis when conflict exists throughout the organization, i.e., across all groups, whereas, intergroup refers to two or a few groups in conflict. 6. Interorganizational. In interorganizational conflict, subsystems are entire organizations and the unit of analysis might be an industry, interface with government, shareholder relations, community relations, etc. Management units. Katz and Kahn’s subsystems (see chapter 2) provide definitions of conflict locations or units of analysis from a management perspective. The five subsystems – managerial, supportive, maintenance, production or technical, and adaptive – provide direction for identifying conflict causes and effects across divergent separate, yet interdependent, processes. Similarly, each subsystem could be 8-10 the primary unit of analysis if the source of conflict resides within that unit (e.g., from a communication perspective, this would most likely be an intrapersonal, interpersonal, and intragroup system). Conflict Location Matrix Conflict mus t be located before actual management can begin. Once isolated, attempts must be made to keep it from spreading to other parts of the organization when consequences are negative. Even if effects are constructive, management is required. Conflict location begins with a methodical examination of all potential settings by responding to a series of questions: 1. Is there discrepancy within an individual employee, i.e., intrapersonal? 2. Is there conflict between the employee and others, i.e., interpersonal? 3. Is there conflict within the work group, i.e., intragroup? 4. Is there conflict between work groups, i.e., intergroup? 5. Is there conflict throughout the organization, i.e., intraorganizational? 6. Is there conflict between this organization and an internal individual, group, organization, i.e., interorganizational? Each question must be addressed in order to locate and constructively manage the situation. Internal conflicts often require different strategies than external conflicts. It is usually advantageous to manage internal and external conflicts separately, even though they may be part of the same problem. In this way, conflicts can be localized. The Conflict Location Matrix was developed (Cummings, Long, & Lewis, 1981 & 1986) to visualize the integration of communication and management issues that must be considered when managing conflict (see figure 8-1). The matrix is useful as a checklist and guide for localizing conflict. 8-11 If, NO, proceed downward Evidence of conflict intrapersonal If it is a process or content problem, go to chapters 1-4 for strategy options. interpersonal intragroup If it is related to information exchange, go to chapter 5 for strategy options. If, YES at any unit If it is related to problem/solution identification, go to chapter 6 for strategy options. intergroup If it is related to behavior regulation, go to chapter 7 for strategy options. intraorganizational If it is related to conflict management, go to chapter 8 for strategy options. Interorganizational Figure 8-1: Conflict Location Matrix Precision in identification facilitates localizing. This means that boundaries or units of analysis are defined as precisely as possible and then managed in that context. Use of the matrix also is predicated upon an old, “arm chair” philosophy that extols – “if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it!” A healthy amount of theory supports this philosophy. Regardless of the manner in which conflicts surface, management begins with interpersonal assessment. If the source is identified as solely within the intrapersonal location, then the conflict manager asks if the source of conflict is related to process, content, or function (both communication function and organization function). If it is beyond the intrapersonal setting, the same procedures follow for each subsequent level. In this way, thorough conflict definition and management a lternatives are considered. 8-12 Conflict Management Strategies After conflict is located, localized, and defined, strategic option selection is next. There are three general communication strategies used to manage conflict: Power, compromise, and creative alternatives. These strategies are similar to win-win, loselose, and win-win concepts used in negotiation strategy. For the most part, additional strategies are derivatives of these basis approaches. Although some may prefer a particular approach, research and practice suggests there is no single, best strategy for all circumstances. Power. Power is a win-lose move used when the ability to control rewards and punishments is perceived. This strategy occurs when one person “wins” at the expense of the “other.” Power is a poor basis for winning popularity contests. However, this approach is efficient and occasionally effective if the manager will retain power for some time. This strategy, which is frequently viewed as coercive, is most effective for short-term use within volatile, uncertain environments. In addition, when work is programmed (only one right way to perform a process), power will most often be an appropriate approach. It is clear, though, than power cannot be used to change attitudes, feelings, or socio-emotionally based differences. It is human nature to resent those who predominantly use power strategies. So, sometimes there is merit in losing “gracefully” in a power play; there is also merit to winning gracefully. The more power is used, the less effective it becomes. Early wins may lead to later losses. While power may be effective at times, it should be used sparingly. Finally, an ominous warning for winners: losers don’t always stay losers; retaliation is possible (Schelling, 1960). When the direction of dependency changes, the winners may find themselves losers when it really hurts. Compromise. “Lose-lose” is descriptive of compromise strategies. In a compromise environment, parties bargain to gain as many of their objectives as possible. This often requires making concessions or giving up some things that are desirable. Thus, during compromise everyone loses something as a middle-ground solution is sought. Compromise is probably the most common type of strategy used in 8-13 American corporations. They are certainly studied and discussed more than any other method. This approach emerges when parties are mutually dependent – this allows leverage to all participants. Consequently, compromise requires more time that power strategies. Furthermore, compromise may be the only alternative when the content of conflict in personal – socio-emotional or person-related conflict cannot be managed through a power play. Organizations that constantly use compromise may inadvertently be encouraging individuals to misrepresent organizational realities. For example, budget through compromise often creates overstatement of need because of expected percentage reductions. This “padding” may be generalized beyond budget issues and into other areas. This can result in conflict management based on untrue or invalid information. Creative Alternative. Creative alternative strategies have the goals of benefiting all parties involved, a win-win philosophy. This approaches requires consensus or collaboration (Thomas, 1976). The aim is to reach an agreement in which all parties achieve their objectives. This is the most time consuming strategy. These approaches require that people spend less time attempting to get others to agree with the “rightness” of their own way of doing things, and more time stimulating others to cooperatively search for a solution. This is done by using the problem/solution identification function of communication. In other words, parties redefine the nature of the problem, usually discovering solutions that satisfy everyone’s needs. When this is done, it is very common to find that conflicting short-term goals created conflict. And, when a longer time orientation is considered, conflict often disappears or is minimal. Thus, there is more open solution seeking, less protection of predetermined positions, and less negotiation through advocacy. It is overly idealistic to say this approach should always be used. This approach may not be appropriate when there are time constraints, when profound adversarial relations exist, or when the nature of the problem is not conducive to consensus or collaboration. In such cases, compromise may be a better option. 8-14 Conflict Management Tactics Conflict is most often managed by the participants. In some cases, an impartial third-party may intervene Third-party intervention. When a third-party intervenes, they should enter as a mediator or arbitrator. Mediators do not impose a settlement; arbitrators are responsible for reaching a settlement, dictated by the arbitration process and formally sanctioned authority (Thomas, 1976). At times, arbitration is necessary to stop deadlocks, such as those found in union-management negotiations. Although arbitration reach a solution, that does not necessarily reduce hostility. Three alternative approaches to third-party intervention are: 1. Collaboration. This is a preferred creative alternative approach. It implies that parties should negotiate rationally. 2. De-escalation. When a conflict contains significant emotionalism, participants view each other with mistrust. So, the third-party’s aim is to reduce the level of conflict intensity while opening channels of communication and pointing out disadvantages of continued hostility. Specific techniques may include roleplaying, sensitivity training, risk taking, and active listening. 3. Facilitation. When conflict exists, is detrimental, and is being avoided by participants, the third-party’s goal may be to facilitate a confrontation. Often, parties in conflict avoid facing one another in order to maintain the appearance of harmony. In this case, the third party must specify potential disastrous consequences, i.e., increase the stake (Thompson, 1976) of further conflict avoidance. Principles. It is impossible to eliminate conflict, and, probably undesirable to do so. Yet, conflict must be managed to maintain constructive effects. Effective management can be hastened by following these seven principles: 8-15 1. Focus and contain conflict where it is most easily managed. Locate and localize before spending a lot of time examining external conditions. The external/internal distinction allows different approaches for different settings. Furthermore, managers should minimize internal conflict while optimizing external conflict. Why? Because externalized conflicts motivate internal cooperation; internal conflict reduces cooperation. 2. Control the level of threat. Threat is extreme when the “trust” climate is low. When threat is perceived at severe, fear increases and avoidance is common. This leads to isolation and increased conflict intensity. Supportive environments reduce threat levels; defensive climates increase threat levels. 3. Clarify rules, norms, and policies for communication beyond formal channels. Communication norms are generally not considered beyond the formal line chart. Consequently, employees are often in a quandary when conflict exists with a supervisor. Few policies can be all inclusive, and exceptions to the norm are often the “norm!” Alternative approaches, beyond the hierarchy of authority should be considered. If not, there will be a tendency to use power strategies most often. 4. Identify conflict early. Generalized conflicts often begin in a more easily managed, localized context. Ignoring localized conflict because it appears unimportant is a costly mistake. Conflict may intensify and become disruptive. 5. Balance dependencies. Organizational structure is usually based on mutual dependence, both horizontally and vertically. Conflicts are difficult to manage when parties perceive little mutual dependence. This often occurs when supervisors and subordinates feel the other is not needed to accomplish goals. In this case, there is little motivation to settle conflicts constructively. 6. Evaluate motivational preferences. Motivational theorists indicate that individuals develop styles of motivation. Some people are intrinsically motivated (i.e., personal needs or from within) while others are extrinsically motivated (i.e., 8-16 by externally applied pressure); and, some are motivated by a combination of both. Thus, one’s locus of motivation will have an impact on the effectiveness of particular strategies. 7. Use the appropriate strategy. This may be obvious, yet the “best” alternative may not be readily apparent. Successful management requires knowing which strategy to use and when to use it. These considerations require consideration of liabilities and assets associated with power, compliance, and creative alternatives. Simultaneously, the conflict manager must be aware of their personal management bias or preferred style. One’s style predisposes behavior in a certain direction and sometimes that approach is inappropriate. Strategy should be based on location, subsystem, process, content, and function. Personal Conflict Management Styles Over time individual behaviors become fixed and somewhat resistant to change. People tend to use those behaviors that “work” when managing their social affairs. Likewise, they adopt preferred ways of managing conflict. In fact, personal preference for communication behavior influences whether conflict is escalated, maintained, reduced, or avoided (Frost and Wilmot, 1978). At the simplest level, personal conflict management style can be characterized by the participants’ desires to satisfy their own interests and the interests of the party with whom they are in conflict (Thomas, 1976). (Figure 8-2 is an adaptation of Thomas’ [1976] conceptualization of style using descriptions from the a uthors and Buckholz, Lashbrook, and Wenburg [1976]). Neglector. The neglector is low is assertiveness and responsiveness. They tend to be critical, indecisive, stuffy, picky, moralistic, serious, exacting, and orderly. These characteristics may lead to excessive delays in managing conflict. As a result, this behavior reflects avoidance and neglect (Sillars, 1982; Thomas, 1976). Accommodator. Accommodators are low in assertiveness, yet very responsive. They are accommodative, seeking to satisfy another’s concerns while avoiding their own needs (Thomas, 1976). Their orientation is to avoid conflict; that is, 8-17 they use a strategy of non-confrontation at all costs. Their communication is characterized by denial, being indirect, ambiguous conversation in order to shift topics away from disagreement. They are often amiable, conforming, unsure, ingratiating, dependable, awkward, supportive, respectful, willing, and agreeable. HIGH Driver Win-lose, Power strategist, dominator Compromiser Lose-lose strategist Assertive Toward Own Goals LOW Expressive Win-win Creative alternative, strategist Neglector Avoidance, slow paced, analytic Accommodator, You-win, appeasement Figure 8-2 LOW Responsiveness to Others HIGH Driver. The driver is low in responsiveness, but highly assertive toward achieving his or her own goals. They seek to win at another’s expense. High-level competition is a dominant activity. The driver is pushy, severe, tough, dominating, harsh, strong willed, independent, practical, decisive, and efficient. Compromiser. The compromiser takes a moderate position on responsiveness and assertiveness. Compromisers reflect a blend of all other positions. Although they feel are parties positions are important, they often view extended conflict as dysfunctional and wish to reach reconciliation as expeditiously as possible. Consequently, they frequently use lose-lose strategies so the organization can get on with its activities. 8-18 Expressive. Expressives are high in assertiveness and responsiveness, skilled at making intuitive judgments, excitable, undisciplined, dramatic, and friendly (Sillars, 1982). They opt for win-win strategies, seeking mutual satisfaction for all. They seek agreement, endeavor to maximize trust, share information, and seek common ground while attempting to maintain a positive, communicative climate. Thomas (1976) described this behavior as beyond sharing or compromise, representing a desire to fully satisfy or integrate the concerns of all parties and not taking advantage of another. 8-19