Getting it right for families - Early Intervention Foundation

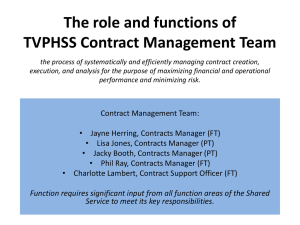

advertisement