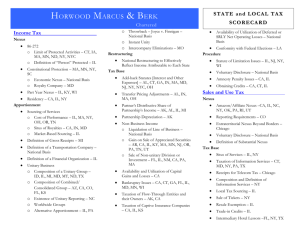

Congressional Intervention in State Taxation

advertisement