Reviews - Bad Request - University of Richmond

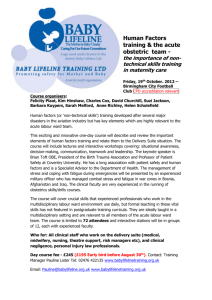

advertisement