Storytelling: Tradition and Preservation in Louise Erdrich's Tracks

advertisement

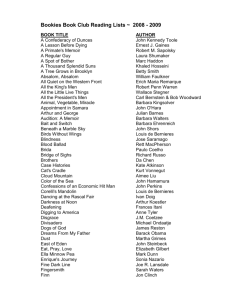

Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma University of Oklahoma Storytelling: Tradition and Preservation in Louise Erdrich's Tracks Author(s): Jennifer Sergi Source: World Literature Today, Vol. 66, No. 2, From This World: Contemporary American Indian Literature (Spring, 1992), pp. 279-282 Published by: Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40148133 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 16:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma and University of Oklahoma are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Literature Today. http://www.jstor.org Storytelling: Tradition and Preservation in Louise Erdrich's Tracks By JENNIFERSERGI Withoutstoriesthere is no articulationof experience: people would be unable to understandandcelebratethe experiencesof self, community,and world.And so culturesvalue the tellers of stories.The storytellertakes what he or she tells - his or her own or that reportedby fromexperience others and in turn makesit the experienceof those who arelisteningto the tale (WB,87). The storyteller relies on memory (his or hers and his or her listener's)and createsa chainof traditionthatpasseson a happeningfrom generationto generation. Louise Erdrich is just such a storyteller.In her thirdnovel, Tracks(1988),she not only chroniclesthe story of the Chippewas'struggle to preserve their land and culture;she also gives us the story of these stories and their tellers as well. She is telling this novel "the Indian way."The "artistryof the Indian 'word sender' characterizesreality: peoples, landscapes, seasons, tonalizes, lightens, spiritualizes, brightens, and darkens human experience,all the while working with the reality that is" (KL, 223). This reality is shown to readersby two storytellers who alternate chapters, in separate,very distinct voices: Pauline, a young mixed-bloodwho is confused and psychologicallydamagedby her unbalanced commitment to Catholic martyrdom and Chippewatradition;and Nanapush,a wise old tribal leadergifted in the ancient art of storytelling.It is throughNanapushthat Erdrichcapturesthe act of Indian storytelling.It is written down, but Erdrich wishes to recordand preservenot just the memories, intertwinedcloselywith personalhistoryand a sense of loss, but a cultural tradition, one that is oral, performed,formulaic,and perpetuatedby the storyteller, who learns the rhythms and melodies- the craft- and expands,ornaments,and variesthe tradition his or her own way. Thus Erdrich's Native American,and more specificallyChippewa,"tracks" areevidentin her narratives,if not as those of the one who experiencedit, then as those of the one who reportsit. How this oral tradition and history is being recordedis important,therefore,and "tracingthe connective threads between the cultural past and its expressionin the present"becomes a primaryfocus of scholars as well as novelists (KL, 2). How are translatorsand NativeAmericanartists,like Erdrich, bringingthe oral and mythic traditionsof their ancestorsinto print for native and non-nativereaders? Erdrich does this in a number of ways in Tracks: 1) she capturesthe formandpurposeof oralstorytell- ing; 2) she includes the contents of Chippewamyth and legend;and 3) she preservesthese culturaltraditions in a voice that harksbackto the old as it creates anew. Kenneth Lincoln, a Native American literature scholar,is also exploringthe natureof the transition from oralityto writing, and within his definition of Indianstorytellinghe describesthe "story-backed old man giv[ing] the child eyes and voices, narratives that touch and are carriedfor life: words incarnate, flesh-and-bloodties, an embodiedimagination.And the tribal backboneextends through ancestorswho carryhistoryin theirbodies"(KL, 222).The fictional old man"is Erdrich's prototypeof this "story-backed narrator,Nanapush.Nanapushis telling the story to his adoptedgranddaughterLulu: "Mygirl, I saw the passingof times you will neverknow."He knowsthe old ways: "I guided the last buffalohunt. I saw the last bearshot. I trappedthe last beaverwith a pelt of morethantwo years'growth.I spokealoudthe words of the governmenttreaty, and refused to sign the settlement papersthat would take away our woods and lake"(2). He also tells Lulu how she fits into this history:"Youwere born on the day we shot the last bear"(58). Moreover,much as in Indianstorytelling,it is not only whatNanapushhas to say and to whom,but also the way in which he says it that is important. Nanapush'snarrativestyle points to the novel'sroots in Chippewaoraltradition.Erdrichis sensitiveto the immediatedifferencebetweenthe printedword and the spoken, and she effects an accommodationbetween her printed text and her narrator'sdelivery. The stylistic devices of repetition and parallelism, employed as early as page 2 of the novel, work to createtension,balance,and symmetryin the wordsof Nanapush.His wordssuggestthe rhythmsof speech: at key moments in the narrative,readers sense a whisperedstatement,an abruptphrase,a long pause. Before he tells the story of how Margaretloses her braids,for instance,he leads in with: "I can only tell it step by step" (109). Erdrichalso continuallyand skillfullyremindsus of his audienceand the intimacy attachedto their relationship:"This is where you come in, my girl, so listen" (57). Lulu sometimes grows tired of the long story, and in his own style Nanapushmanagesto reprimandthe youngsterand, in the process,remindher of her rootsand her role in this storytellingtradition:"I madeher sit down and listen, just the way you are sitting now. Yourmother alwaysshowedthe properrespectto me. Evenwhen I boredher, she madea good effortat pretendingsome interest"(178). 280 WORLD LITERATURETODAY Erdrich'snarratornot only servesto remindus of the importanceof the ancient art of storytellingto a tribe, but his name also recalls the novel's debt to Chippewamythic tradition.In Chippewawoodland who myth Nanapush is the trickster-transformer "wandersin mythic time and space between tribal experiencesand dreams"(GV, 3). He is a teacherand healerand upholderof ancientand living traditions; but he is also human. He is sometimes prone to violence and overactiveappetites.This paradoxical characteris part of Chippewacreationand ceremonial stories. In my researchof Chippewatradition, myth, and legend the storiesaboutthe trickstervary, as does the spelling of his name (most likely because of phonetic transcriptionfrom oral tradition), but there are several similarities in all of them to Erdrich'sNanapush.(I must pause here to make a distinction.Chippewais a comparativelymodernand English term for the tribe; an older term is Ojibway. The name for these people in the languageitself is Anishinaabe. Erdrichuses both ChippewaandAnishinaabe in the novel; all three were found in my research.)In most of the translationshe possesses magic and wit. He plays tricks and is the victim of tricks. He is fond of and is good at hunting. He travels in a birchbarkcanoe, and the Anishinaabe honor and respect him. In chapter 3 of Tracks Nanapushtells us partof the originof his name:"My fathersaid, 'Nanapush.That's what you'll be called. Becauseit's got to do with trickeryand living in the bush. Because it's got to do with something a girl can't resist. The first Nanapushstole fire. You will steal hearts'" (33). Erdrich'sOld Nanapush,then, servesa triplepurposein remindingreadersof Tracks of the importanceof tribal tradition,mythic condition, and storytelling. Along with this trickster figure, there is other evidence in the novel that Erdrichis interestedin preservingand presentingChippewaculturaltradition to her audience. I cannot know for sure if Erdrichheard these stories as a child, read the accounts and researchof Chippewamyth, tradition, legend, and religion,or discussedthem as a member of an academiccommunity.However,I do knowthey areincorporated,integrated,and an importantpartof her novel. So, like the creationfigureNanabushand her storytellerNanapush,Erdrichimaginesand desires her own variationof the mythic stories for the I Louise Erdrich, 1989 SERGI enjoyment and knowledge of her modern reading audience. The setting of her novel is the fictional Matchimanito Lake. It may not be a real geographiclocation, but MatchiManitois an evil manitoin modern Ojibwamyth (CV, 82). The name of the lake is not the only reminder of Chippewa myth in Tracks. There is talk of windigosand manitous,buryingthe dead in trees, dreamcatchers,Jeesekeewinini(medicine man),and "Anishinabecharacters,the old gods," as Nanapushrefersto them (110). In chapter6 Pauline gives us a description of "the heaven of the Chippewa,"whereFleurgoes to gamblefor the life of her child. The gambling crowd "play for drunkenness, or sorrow,or loss of mind. They play for ease, they play for penitence, and sometimes for living souls" (160). Gerald Vizenor, a mixed-blood member of the MinnesotaChippewatribe as well as a teacherand scholar,recordsa numberof the oral creationstories 281 canoes and drownedIndians."In some tales, however, it "fedand shelteredthose who fell throughthe ice." Erdrich uses this dialectical being throughout Tracks.When Fleur returns to Matchimanitofrom Argus,the townspeopleattributegood fishing and no lost boats to Fleur's ability to "keep the lake thing controlled"(35). Her specialconnectionto Misshepeshu is even thoughtto be sexual,and the paternityof Lulu is questioned:"Lulu'seyes blazedbrightas his, . . . eyes hollow and gold" (70). Just before Pauline takesher vows andbecomesSisterLeopolda,she tells the story (in chapter8) of her entanglementwith the lake monster. For Pauline, who has just recovered fromself-inflictedburns,the lake monsterrepresents the devil. She is delusionaland very confusedabout her religious faith and her Chippewatraditionalbeliefs: "Christhad hidden out of frailty,overcomeby the glitter of copperscales,appalledat the creature's unwinding length and luxury. New devils require in his book The People Named the Chippewa: Narrative new gods" (195). She makes a last visit to MatchiHistories.In his prologue Vizenor recounts a story manito "determinedto wait for my tempter, told by Odinigun, an elder from the White Earth the oneLake, who enslaved the ignorant, who damned Reservation,telling of Naanabozho'sgambling in them with belief" (200). She tells her story of a "the land of darkness."In this story Naanabozho violent encounter with the monsterin which sexual, must play the greatgamblerfor "the destiniesof the she him with her rosary, but the thing strangles tricksterand tribal people of the woodland."The a human . . . the physical form of "grew shape tone and,of course,the settingof thesetwo storiesare (202-3). She feels no guilt for similar; the stakes and energies are high. The out- Napoleon Morrissey" the father of her child, because"he had murdering comes are very different,however:Fleur'sbaby dies, ... as the water appeared thing, glass breastplateand while Naanabozhosucceedsin not losing his tribes' iron Pauline believed she (203). burning rings" spirit to the land of darkness. "tamed the monster that night, sent [him] to the Oneof the mostprevalentand important"signs"of bottom of the lake and chained there by [her] Chippewamyth in Tracksis Misshepeshu,the water deed. . . . [She] was a poor and [him] noble creaturenow, monster.In the novel Misshepeshu'sorigin is tied to dressedin earth like in furs like Moses PilChrist, the arrival of the Pillager clan on Matchimanito medicine man and Fleur's lager [the brother], draped Lake.The monsterwas thoughtto be responsiblefor Fleur's powers and the demise of her enemies. in snow or simple air" (203^). This description symbolizesthe utterconfusionsome Chippewacould Pauline describeshim in chapter2: feel because of the crisis in their belief system He's a devil, that one, love hungry with desire and brought on by Christianinfluences. Of course Paumaddened for the touch of young girls, the strong and line is an extremeexampleof the pull betweenCathodaring especially, the ones like Fleur. lic teachings and Chippewatraditions,but Erdrich Our mothers warn us that we'll think he's handsome, uses the lake monster,the underwatermanito Misfor he appears with green eyes, copper skin, a mouth shepeshu, in this case as a symbol of the crisis of he into his tender as a child's. But if you fall arms, identity for Pauline. sprouts horns, fangs, claws, fins. His feet are joined as one and his skin, brass scales, rings to the tough. ... He Misshepeshuserves severalsymbolic purposesfor holds you under. Then he takes the body of a lion, a fat Erdrich: he is an example of native tradition and brown worm, or a familiar man. . . . He's a thing of dry lore; he bringsthe crisisbetweenChippewamyth and foam, a thing of death by drowning, the death a ChipCatholicteachingsto a state of rupturein the novel; pewa cannot survive. (11) and the languageused to describehim becomessymErdrich'sdescription of the lake monster is very bolic of the storytelling itself. According to similarto that given by ChristopherVecsey,another Nanapush: scholarinterestedin recordingChippewaoral myth. Talk is an old man's last vice. I opened my mouth and Accordingto his accountof this Chippewamyth, the wore out the boy's ears, but that is not my fault. I UnderwaterManitois "associatedwith both the lion shouldn't have been caused to live so long, shown so and the serpent"(CV, 74). It inspiredboth awe and much of death, had to squeeze so many stories in the corners of my crain. They're all attached, and once I start terror,as well as reverence,and was thought to be there is no end to telling because they're hooked from responsiblefor both malicious and good deeds: "It one side to the other, mouth to tail. (46) could cause rapidsand stormywaters;it often sank 282 WORLDLITERATURETODAY The stories are circular and continuous and serpentlike. By telling tribal stories, singing old songs, Nanapushgives his culture a chance for continuation: "Duringthe yearof my sickness,when I wasthe last one left, I saved myself by startinga story. ... I got well by talking. Death could not get a word in edgewise, grew discouraged,and traveledon" (46). He not only discourageddeath, but he encouraged life and continued his name with his storytelling. When a priest comes to baptize Fleur's illegitimate child, Nanapushtells him the baby is his: "There were so many tales, so many possibilities, so many lies. The waterswere so muddy I thought I'd give them anotherstir"(61). He latersavesthis child with his talking. Nanapush knew "certain cure songs, words that throw the sick one into a dream . . . holding you motionless with talking." Lulu was "lulled with the sound of [his] voice" and cured of frostbitewith Nanapush'sancient gift (167). For Nanapush, being a talker was a form of survival; he used his words and his "brain as a weapon"(118).This gave him his identity as a tricksteranda leader(32). He learnedto askquestionsand tell stories "without limit or end" (145). As much poweras the spoken word has for Nanapush,he has learned to fear the printed words the white man brings to his land: "Nanapushis a name that loses power every time that it is written and stored in a governmentfile" (32). Still, when he is aboutto lose his land, he admitsto FatherDamien that he should havetriedto "wieldinfluencewith this [new]method of leadingotherswith a pen andpiece of paper"(209). As Nanapushis exploringthe dichotomousnature of the transition from orality to writing, so is Erdrich.Readersare learningof the Chippewas'oral traditionthrougha printedtext. Erdrichshows this dualitythroughNanapush.Althoughhe expresseshis disgust with the "barbedpens" of the bureaucrats encroachingon his people, making them "a tribe of file cabinets and triplicates,a tribe of single-space documents,directives,policy.A tribeof pressedtrees. A tribe of chicken-scratchthat can be scatteredby a wind, diminished to ashes by one struck match" (225). Nanapush tells us that he saves his granddaughterand bringsher to his home with papersand records from the church: "I became a bureaucrat myself ... to drawyou home"(225). It is interesting that Erdrich chooses the word draw in this case, evokingan imageof the pen ratherthan of the voice. She realizesthe conflict,to which she in partcontributes: the Indian"oraltraditionof medicine,religion, history, and tribal ceremony bridged from living ritual performanceinto the marketplaceof print" (KL, 82). Nevertheless,for Nanapushand the Native Americans,the lastwordmustbe survival.His stories preserveand pass along, tracingand trying to make sense of living history.Erdrichgives us these stories in print; throughher languageshe gives poetic voice and historical witness to human events, which is what all cultures expect from their storytellers. Universityof Rhode Island Works Cited Victor Barnouw. WisconsinChippewaMyths and Their Relation to ChippewaLife. Madison. University of Wisconsin Press. 1977. Walter Benjamin. Illuminations. New York. Harcourt, Brace & World. 1955. (References use the abbreviation WB.) Louise Erdrich. Tracks. New York. Henry Holt. 1988. Basil Johnston. OjibwayHeritage. New York. Columbia University Press. 1976. Ruth Landes. Ojibwa Religion and the Midewiwin. Madison. University of Wisconsin Press. 1968. Kenneth Lincoln. Native AmericanRenaissance.Berkeley. University of California Press. 1983. (References use the abbreviation KL.) Christopher Vecsey. TraditionalOjibwa Religion and Its Historical Changes. Philadelphia. American Philosophical Society. 1983. (References use the abbreviation CV.) Gerald Vizenor. The People Named the Chippewa:NarrativeHistories. Minneapolis. University of Minnesota Press. 1984. (References use the abbreviation GV.)